This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

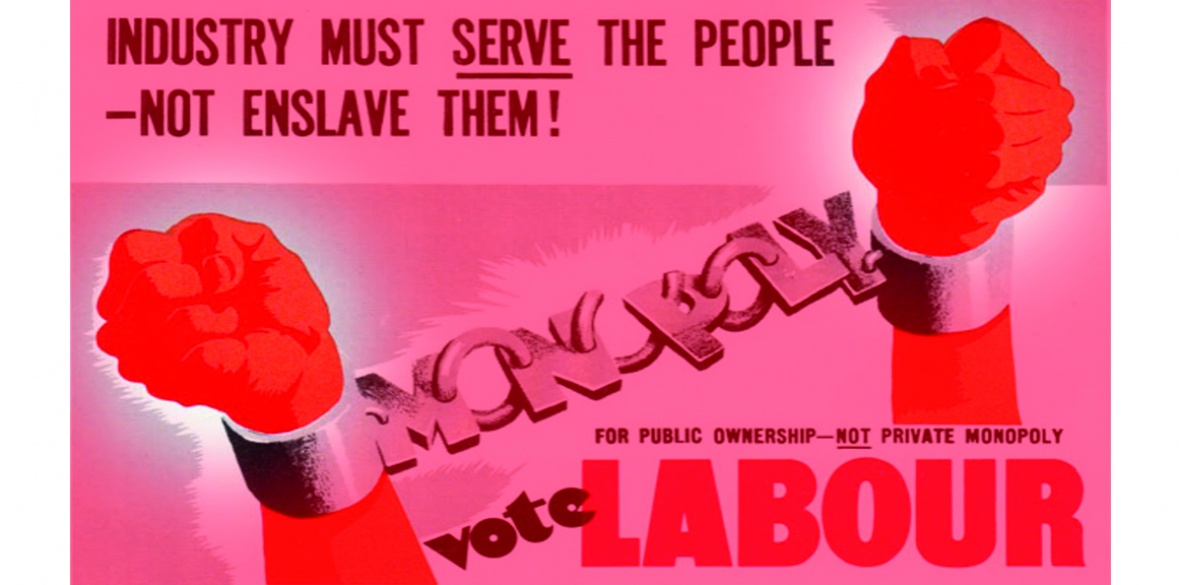

THE labour movement takes understandable pride in the achievements of 1945 — the bold legislative programme of Attlee’s government which changed Britain, permanently for the better.

Decades of neoliberalism have still to undo much of the welfare state or to complete the privatisation of the NHS. When it came time to define the nation, at the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympics, it was the NHS that was showcased as the crowning achievement of this island’s story.

The onset of the pandemic has confirmed that, through the spontaneous outpouring of public support for the NHS through painted rainbows and applause for staff and care workers. The fruits of socialism work and are popular.

Yet, these achievements did not happen by chance, or come without a fight. It took over half a century of campaigning and organising by the new unions to establish the arguments for socialism and the terrible advent of the second world war to shift attitudes — among both the public and civil servants — towards planning and market controls and from the private sphere to the collective.

It was the trade unionists who forced the tempo: they sat on the trades boards and the wages councils, delivered in terms of production and did the essential hard and unglamorous work.

It was Ernest Bevin who was the architect of industrial victory as minister of Labour from 1940-45; it was Manny Shinwell — the Clydeside MP — who nationalised the mines; and Aneurin Bevan who drew up a comprehensive model for the NHS, virtually from scratch.

Despite different personalities and priorities, they shared a common grounding in the experience of work and trade union struggle; they offered hope and, most of all, they worked to a plan.

The scope and the success of that which was achieved between 1945-51 has provided an enduring definition and political legitimacy for the left. It is one of the few things that we can all seem to agree upon. The trouble is that the labour movement rapidly came to see the achievements of 1945-51 as a final settlement, that could not be bettered or extended.

It did not seek to push further down the roads of full economic and industrial democracy, towards worker participation and control, the replacement of competition with co-operation, the regulation of markets and an assault upon rentier capitalism and private monopolies.

It did not, as Bevan had wanted, extend the reach of the NHS to the opticians and the dentists and to invest in preventative health measures alongside doctors’ surgeries and hospitals.

It abandoned industrial planning and market regulation. It forgot collective rights and began to pander to individual needs. As a consequence, we have been forced back upon the defensive and — perversely in the language of the free market right — have seemed “conservative” in the face of assaults by “radical” deregulators, hedge-funders and multinationals.

Those very qualities that delivered the victories of 1945 — tenacity, self-belief, the engagement with big ideas and the pursuit of seemingly unrealisable ideals — have been precisely the things that have been jettisoned through partnership schemes, “new realism” and the adoption by the unions of managerial methods and language.

In short, we have become scared of our own shadows. We have no programme, no core belief, no red standard to rally around when the tempests rage.

So, instead of paying a dull and formulaic lip-service to the achievements of the past, it is perhaps high time that we sought to reclaim the values, the tenacity and the vision that made them possible.

This, naturally, involves risk, invites derision and mobilises — as the recent history of the Labour Party demonstrates — the full force of the mainstream media and power of the capitalist and rentier classes against us. But it is the fight that we must have if we are to remain a movement and not only regain but exceed that which has been lost since ’79.

The pioneers of our movement would have had no trouble instinctively grasping this point. It was a long march from 1889 to 1945 and many of brightest and best — such as Eleanor Marx, Robert Tressell, Keir Hardie and John Maclean — were derided as hopelessly idealistic dreamers and did not live to see the day when Attlee’s government took its seat on the government benches, to the strains of the Red Flag. Yet, they thought ahead, delivered the hard detail and fought through the abuse, hardship, ruin and despair.

A brief overview of the successes and the problems faced by the labour movement will demonstrate how they did it and those principles, in thought and action, that will secure us victories once again.

The Labour governments of 1945-5 inherited an unprecedented system of wartime controls, regulations and initiatives that had already acknowledged the importance of collectivity and a universal right to welfare, regardless of the ability to pay.

If there could be a fair distribution in wartime, then there should also be fair shares during peace. This resulted, within two years, in the creation of the NHS, a national insurance scheme and the nationalisation of the Bank of England and the power generating industries, with transport, iron and steel not far behind.

Furthermore, this was accomplished against the backdrop of a war-ravaged nation, where four million homes had been bombed, where many thousands of lives were shattered through disability, where the largest external debt in history had been accrued and a $650 million bill was called in, almost overnight, by the Truman administration’s decision to halt Lease-Lend in an attempt to destroy British socialism in the bud. So much, then, for the “special relationship.”

Yet, as Labour’s 1945 manifesto pointed out: “The test of a political programme is whether it is sufficiently in earnest about the objectives to adopt the means to realise them.”

These included “drastic policies of replanning and … keeping a firm constructive hand on our whole productive machinery” and significantly, a commitment to the “freedom of the trade unions” whose members had done so much to ensure victory.

This commitment involved the removal of all the anti-union legislation enacted in the Trades Disputes and Trade Unions Act of 1927. Can we honestly envisage our unions, collectively, forcing through such an unequivocal argument for their worth, centrality and democratic freedoms to fight and organise, today?

Against these essential, true, freedoms were the false freedoms that served to “exploit other people… to pay poor wages and push up prices for selfish profit… to deprive people of the means of living full, healthy, happy lives.”

These same false freedoms have been used to dazzle us and we have been all too keen to accept them in recent years. How often have we heard senior trade unionists talking the language of “professionalism,” “realism” and “compliance?”

A thousand-and-one buzz words have eroded our self-confidence and replaced belief and gut instinct with greyness, calculation and smug spin.

We have retreated away from arguing for progressive taxation, the complete unshackling of our own movement and from expressing the fire in our bellies that defines us and drives us forward.

We cannot live on a borrowed vitality. If socialism has no blueprint, no remedy for the crisis and misery inflicted by gangster capitalism, then all we have left are the forms and not the reality of 1945.

The unions remain an instrument — and perhaps the best instrument — for transforming the economic structure of society.

We need to be clear about our own role and our own constituency. We need, once again, to take to heart the need to define those “objectives to adopt” together with “the means to realise them.”

For, we — and nobody else — represent those who do the work: the work that keeps the lights bright and the power on; the work in our NHS hospitals which makes the difference between life and death; those who manufacture and create; those who feed us and restock the supermarket shelves; those who care for our children as teaching assistants and those who look after the elderly in retirement homes.

They represent the truly productive class and also the squeezed middle, whose taxation makes all else possible. We need to listen to them, to hear and amplify their voices and to reforge the world of work around them in order to replace fear and insecurity with purpose and solidarity.

In doing this we will be far closer to the spirit and content of ’45. And to succeed, we will need to fight not just against Tory austerity but also the self-imposed austerity that we have shackled upon the ideas and ideals of the labour movement, itself.

The great only appear great — as James Connolly echoed Camille Desmoulins — because we remain on our knees. It is time that we stood up and were counted.

Gary Smith is GMB’s Scotland Secretary.