This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

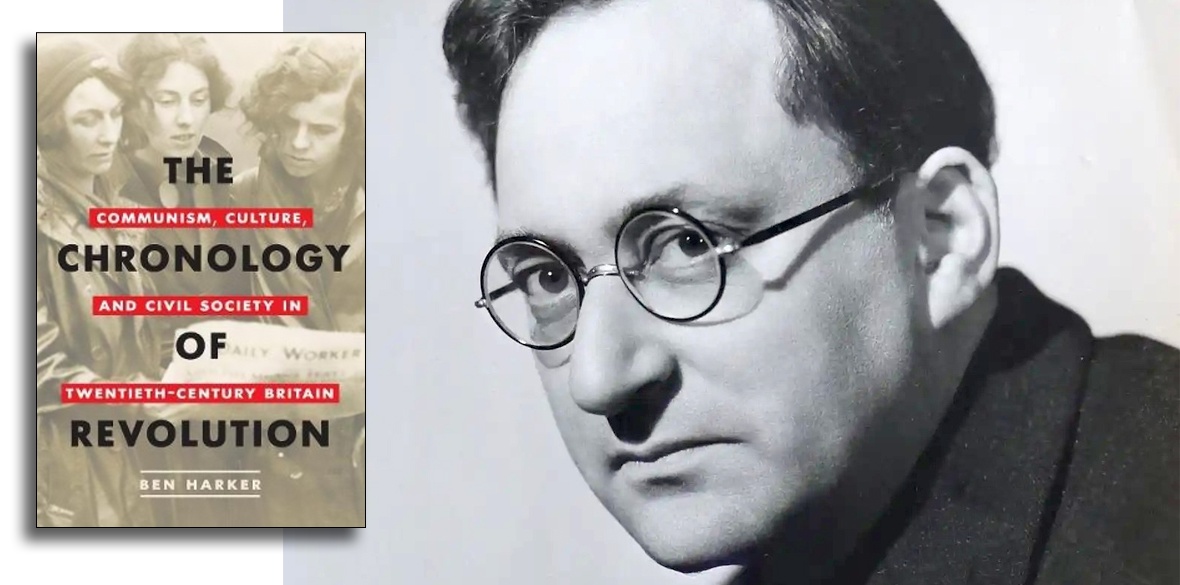

The Chronology of Revolution: Communism, Culture

and Civil Society in Twentieth-Century Britain

by Ben Harker

(Toronto University Press, £63.99)

THIS book represents probably the first attempt to compile a comprehensive history of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Its title is, one assumes, tongue in cheek — a socialist revolution is of course yet to arrive.

The early Bolsheviks expected great things from the Communist Party after its formation in 1920. After all, Britain was the cradle of the Industrial Revolution, with a highly organised proletariat and it provided the basis for the ideas of Marx and Engels.

It was surely the ideal country for a socialist revolution but it never happened. Harker’s book attempts to answer that conundrum or at least suggest reasons why.

Unlike its sister parties in Germany, France and Italy, the CPGB never became a mass party or a significant political force electorally. But its impact on civil life was always considerably greater than its numerical strength.

Harker argues that, rather than simply writing off the party as a Stalinist aberration, as many do, a closer examination of the party’s history could help in promoting socialist renewal and strategy for the 21st century.

Yet though capitalism is facing a systemic crisis, the left is making only uneven advances and lacks coherence.

His book is undergirded by three key convictions — capitalism is inherently incapable of fulfilling the needs of the majority of the people and a transition to socialism remains an ethical imperative — a choice between socialism or barbarism; some version of the party form is indispensable for socialist advance and communist parties remain an unavoidable antecedent in mass anti-capitalist struggle.

Harker argues that one core and abiding problem in realising revolution has been the communist movement’s fundamental underestimation of the resilience of capitalism.

In general, communist parties operated on the basis that revolution was imminent, based on Lenin’s dictum that “imperialism is the highest (and last) stage of capitalism.”

His analytical frame focuses on the underanalysed disjunction between the communist parties “of a new type” attached to the Third International and the developing forms of Western capitalism that proved so resistant to their impact.

Placing the blame on the Stalinist concept of a revolutionary elite and the Soviet Union’s degeneration into an ossified bureaucracy is insufficient, he argues, to answer the question of why Western communist parties failed to achieve revolutions and to seek an answer he explores interlocking economic, political and cultural aspects.

The CPGB began as part of the Communist International, which had its headquarters in Moscow, and the party was modelled on the Bolshevik one, with quasi-military discipline and insurrection as its goal.

Subsequently, the party morphed dramatically. There was the disastrous class against class period between 1926 and 1931, the Popular Front policies of the 1930s, in order to prevent the rise of fascism and class collaboration during the war years to combat the fascist war machine.

Becoming free of Moscow with the dissolution of the Comintern in 1943, there was a commitment to an electoral road to socialism, followed by post-war support for a Labour government in rebuilding a war-ravaged economy.

In all this, the party went through fundamental transformations that were more imposed responses to reality rather than the result of deep analysis.

These changes were largely centrally imposed and not the result of consultation with the party’s members, nor were they communicated effectively to them.

During WWII, once the Soviet Union became an ally and the CPGB swung around to support the war, its members on the ground were playing a vital role and were now readily taken on board by the ruling class in order to more effectively promote the war effort.

Shop stewards in industry played a key role in increasing production, communist scientists like JD Bernal and JBS Haldane were co-opted by the government as advisers and even the BBC employed communists as effective communicators. In the wider cultural field, communists played prominent roles.

This was the high point of party growth and influence, before it was unceremoniously ostracised once the cold war set in.

Despite this, the party continued to have considerable impact on civil life in the country. Its architects were centrally involved in the planning and construction of council housing and public buildings, its other professionals, musicians and artists were influential in their specific areas and the many teachers and educationalists who were party members played key roles in developing new post-war educational programmes and the establishment of comprehensive schooling and the Open University.

Harker takes us back to a time where it was possible to imagine a different world. Critically sharp, yet avowedly recuperative, he asks us to think again about the enabling agency of the party.

His book, meticulously researched, suggests a counterfactual set of directions that the party might have pursued and sketches an alternative history as it does so.