This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

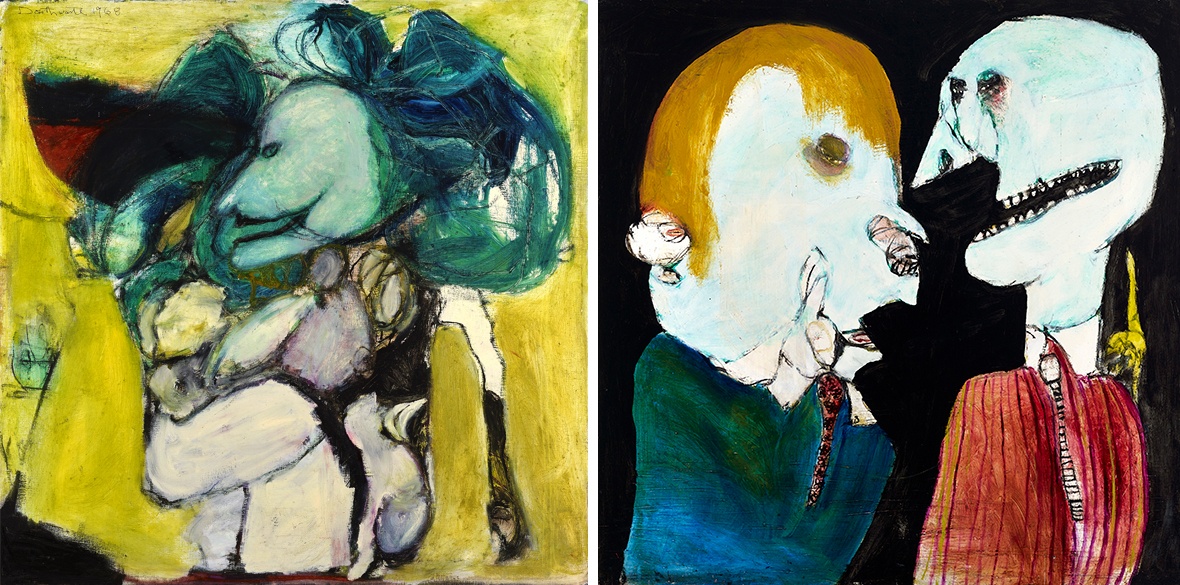

PAT DOUTHWAITE’S greatest supporters in the art world are often termed long-suffering.

One such, who knew her well and has written a brief biography of her, is Edinburgh’s Scottish Gallery Guy Peploe, which hosts some of her work in the On the Edge exhibition next month.

“She was impossible to please and made enemies of her supporters with an impunity that was at once careless and pathetic,” he writes in a monograph.

Douthwaite, born in Glasgow in 1934 and brought up in Paisley, died alone in a B&B in Broughton Ferry, Dundee, only two days away from her 68th birthday.

This extraordinary artist started as a dancer, taking lessons from choreographer Margaret Morris, whose partner was artist John Duncan Fergusson.

He mentored the youngster and when she decided to switch from dancing to the visual arts in the late 1950s, he insisted that she eschewed a formal art education.

Success came with a solo show in Edinburgh in 1958. Douthwaite plunged into a bohemian milieu, mixing with other artists, writers and theatre designers.

She travelled whenever she could, with trips to India, Peru and Mexico.

One of her early 1980s pieces, Village Taxi, depicts an amorphous figure riding in a ramshackle carriage. The luminescent blue oil paint seems adorned with hieroglyphs, suggesting ornate mosaic. It’s also delightfully daft and witty.

It’s her paintings of women, though, which grab the viewer by the lapels.

“People quickly became her subject, at first the dandies and grotesques at once Carnaby Street chic and Soho damaged,” Peploe says.

“They were replaced by archetypal women — none alive, because they would be her natural rivals. She chose Western heroines, like Cattle Kate or the Scottish witch Isobel Goudie.”

The latter, reputed to having confessed in the dark days of 1662, had claimed to be a shapeshifter. She had once transformed herself into a hare, she said, and been chased by a pack of dogs before returning herself to human form.

It’s a perfect choice of subject for Douthwaite, who said she painted many versions of herself, often with animals who have the look of a witch’s familiar.

In Woman with a Reptile (c1970) the figure strikes a dancer’s pose, the head a grinning skull. It is unnerving and mesmerising.

Peploe describes her work as “absolutely controlled; it is beautifully designed. She doesn’t put a mark wrong. There’s nothing naive about this work.”

In some critics’ comparisons with Modigliani and Chaim Soutine, there’s a suspicion that they’re focusing on Douthwaite’s lifestyle rather than her work.

Flamboyant behaviour, fuelled by drug-taking, need not cage this woman into a “peintre maudit” (“cursed painter”) box.

She certainly had an addictive personality and was taking uppers and downers but she wasn’t defined by her mental illness — Douthwaite had bipolar disorder — and, says Peploe: “She was smarter than anyone who diagnosed her mental health.”

Strong women abound in her work, with an exhibition at the Scottish Gallery in 1977 devoted to aviatrix Amy Johnson.

In 1982, her show Worshipped Women at the Edinburgh International Festival was introduced by Robert Graves, whom she knew from a period living in Majorca with her husband, the illustrator Paul Hogarth.

In her 1960 painting Hogey Bear, she produces a dark mass topped with a small, fragile face.

The title was her nickname for Hogarth, though he is not the only figure here. She is too and pregnant with their son Toby.

What does this say about the female? Enveloped by the male or overwhelmed by looming childbirth?

Douglas Hall, first curator of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and definitely a long-suffering supporter, wrote in 2000: “I like to remember Douthwaite as a young woman full of mixed diffidence and hope, embarking on a voyage that was to come near to shipwreck many times.

“Those of us who came into contact with her, though we may often have had to suck our fingers, have some responsibility along with Douthwaite herself for the fact that she has not had proper recognition of her status as a painter of distinction.”

Runs from February 4-27 with a virtual view, lectures and a tour, scottish-gallery.co.uk. Guy Peploe's excellent short film can be viewed at youtube.com/watch?v=iMrVvjR9v08.