This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

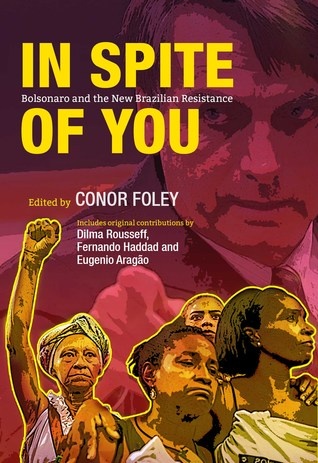

In Spite of You: Bolsonaro and the New Brazilian Resistance

Edited by Conor Foley

O/R Books, £13

THIS little volume explores some crucial themes from the last few years of Brazilian politics and among the contributors are former president Dilma Rousseff, Workers Party (PT) presidential candidate, former education minister Fernando Haddad and former justice minister Eugenio Aragao.

Issues covered include how Jair Bolsonaro was able to win the 2018 presidential election, the growing influence of the security and agribusiness sectors in Brazilian politics, how the “car wash” corruption investigation was leveraged to weaken support for the PT and how the Bolsonaro government is reorienting Brazilian domestic and foreign policy towards US needs.

As one contributor points out, in his 30 years of public life Bolsonaro has consistently and openly promoted a racist, homophobic and misogynist discourse in which he has also argued in favour of torture and dictatorship and expressed a strong hostility to human rights.

He is, to use Rousseff’s pithy description, a “proto-fascist.” How is it possible that such a vile character could win a presidential election?

What emerges from In Spite of You is that although PT candidate Rousseff won the 2014 presidential election, the right-wing opposition was able to make significant gains in congress.

A powerful conservative bloc emerged that came to be known as “Bull, Bible and Bullet,” referencing its origins in the agribusiness, evangelical and security sectors.

This coalition was totally dedicated to undermining the PT’s progressive economic and social policies and was able to start forcing through an anti-worker agenda which led to rising inequality and unemployment, which had reached a historic low of 4.8 per cent in late 2014.

These economic and social problems deepened after the installation of Michel Temer as president in April 2016 following the impeachment of Rousseff.

As often happens with rising poverty and inequality, violent crime also saw a significant increase and this boosted the “tough on crime” narrative of Bolsonaro and his backers in the police, army, judiciary and gun lobby.

Meanwhile the “car wash” corruption investigation was handled by a judiciary that has changed very little in its social profile and class interests from the days of the dictatorship of 1964 to 1985.

Far from being above politics, the judiciary, with the help of the private media, deliberately and systematically used the “car wash” scandal to undermine popular support for the PT.

It was portrayed as being terminally corrupt and inept, even though the details uncovered by the investigation actually showed the PT to be a relatively minor player in an endemic corruption that is a longstanding feature of Brazilian politics.

Eugenio Aragao writes that the “car wash” was “an entirely political process with a clear political aim: to bring down a democratically elected president and instal a more market-friendly replacement.”

The wealthy and powerful agribusiness lobby rallied strongly behind Bolsonaro, attracted by his intense hostility to indigenous Brazilians.

Bolsonaro had after all labelled the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) and the Homeless Workers’ Movement (MTST) as “terrorist organisations.”

In government, he has consistently opposed indigenous land rights and called for the opening up of ever-increasing areas of the Amazon for agriculture.

The media, dominated by a conservative Euro-Brazilian elite, was only too happy to spread the gospel of Bolsonaro-style quasi-fascism, pushing a socially conservative, right-wing Christian agenda that fed into a relatively widespread bitterness among white middle-class Brazilians dissatisfied with the PT’s progressive policies — the protection of indigenous land rights, support for women’s equality, support for LGBT+ rights and affirmative action programmes favouring Afro-Brazilians.

In spite of the sophisticated manoeuvring of the Brazilian elite, it wouldn’t have been able to dislodge the PT from power had it not managed to prevent former president Lula from standing in the presidential elections.

Lula was polling at 40 per cent, compared with Bolsonaro’s 15 per cent, before his candidacy was spuriously ruled out of order, against the specific request of the UN human rights committee.

The PT’s next choice, Haddad, was far less well-known and the road was therefore left open for Bolsonaro.

The result is that Brazil has become part of an incipient Trump world order, waging a ruthless attack on Brazil’s working-class, peasant, indigenous, female, LGBT+ and Afro-Brazilian communities, as well as pivoting away from the PT government’s pro-global South policies and towards total alignment with the US’s “Make America Great Again” strategy.

In Spite of You provides a valuable insight into the rise of Bolsonaro and the state of Brazilian politics in 2020. For those seeking to avert the global upswing of the racist, xenophobic, socially conservative and neoliberal far right, these are crucial topics to explore.