This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

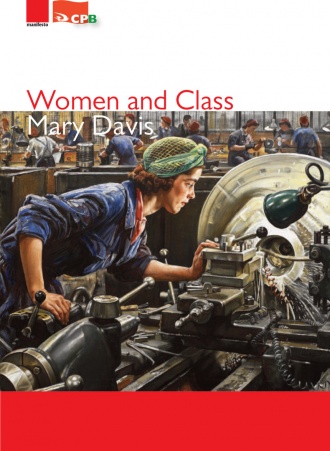

Women and Class

by Mary Davis

(CPB, £4.50)

IN LIGHT of the economic and political crisis facing the working class in Britain and the capitalist world, in which attacks on women’s rights are a prominent feature, the publication of the fourth edition of Mary Davis’s book is more than welcome.

Since its first appearance in 1990, this slim volume has been invaluable to generations of socialist

readers seeking elucidation of the intransigent political and theoretical question of women and class.

So it is to be welcomed that the Communist Party in its centenary year has published this updated and revised edition containing many new sections, including one on identity politics and an updated Charter for Women as an addendum.

Davis’s starting point is the historical confusion in the Communist Party and the wider left over the relationship of women to class, class struggle and socialism itself. In the introduction, she sets out the problem succinctly.

The oppression of women has been consistently underplayed by the state and quite erroneously relegated to a secondary position by the left. Over past decades, there has been a move away from class politics more generally, even on the left, to an individualist politics which threatens the very concept of women’s collective rights.

In this context, she argues, the left requires a systematic analysis of what progressives have long called “the woman question” which “recognises that female oppression is indissolubly linked to the operation and maintenance of the capitalist system” and that the fight to end it is an intrinsic and essential aspect of the struggle for social transformation.

As Davis points out, the oppression of women and black people is not incidental to class society but constitutive of it – the ideologies of racism and sexism serve to divide the working class and thus perpetuate capitalist society. “The key to understanding the situation of women under capitalism lies in the complex and dynamic relationship between exploitation and oppression,” she writes.

In the opening chapter, Davis presents the Marxist view of the origins of women’s oppression with commendable clarity. In contrast to radical feminist accounts that locate it in sexual antagonism between men and women, Marxists see it first and foremost as a product of class society.

Early human societies were necessarily co-operative and egalitarian and the sexual division of labour was not therefore antagonistic. It was only with a change in the productive forces that a qualitative shift took place in relations between the sexes.

In this respect, the work of Friedrich Engels is pioneering. In The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, Engels argues that it was the emergence of property relations based on the production of surplus wealth and the development of patrilineal descent systems for its transmission that led to, in his evocative if slightly misleading phrase, “the world historic defeat of the female sex.”

Yet, as Davis makes clear, while Marx and Engels made crucial links between the workings of capitalism and women’s oppression in their writings, this did not amount to a systematic analysis. There are still many questions that remain unanswered by Marxism-Leninism, not least why women’s oppression persists in socialist societies.

Davis goes on to examine the rival theories that have been advanced to explain women’s oppression. Biological determinism, which maintains that male and female roles are determined by nature, is rooted in religious dogma and social Darwinism and became the dominant ideology of capitalism.

In contrast, liberal feminism challenges its underlying sex-role stereotypes and focuses on women’s political and economic equality within capitalism through legal reform. As Davis argues, this emphasis on legal rights often ignores the specific situation of working-class and black women to the detriment of the women’s movement.

Radical feminism grew in reaction to the limited goals of liberal feminism and picked up on those aspects of sexual politics frequently ignored by the left. Problematically, though, it identifies the conflict between men and women as preceding and transcending class and race conflict.

In claiming to go beyond Marxist analysis, it becomes ahistorical and paradoxically risks affirming the very biological determinism it set out to challenge. Almost the opposite is true of the new gender identity ideology: in advancing a theory of individual choice based on feelings, this ideology substitutes what amounts to sex-role stereotypes for the material reality of sex.

In the former case, women’s class exploitation is downplayed in the interests of sisterhood, while in the latter women’s sexed bodies, the very basis of their oppression in class society, is ignored in the interests of individual rights. Both positions work to alienate the vast majority of women, whose subordination stems from their exploitation and oppression in capitalist society.

Davis advances a Marxist-feminist analysis of the relationship between oppression and super-exploitation within capitalism. While a class theory of women’s oppression cannot itself supply the necessary political strategy, it can provide the framework for much-needed historical and political analysis and thus point the way forward for women.

“The struggle for equal pay for equal work, for subsidised childcare and for the socialisation of other aspects of domestic work, and for other issues of importance to women, such as reproductive and full legal rights, points ultimately to socialism,” Davis stresses. “It is around issues such as these that most women are likely to be mobilised.”

She provides a historical survey of women workers and the women’s movement over two centuries, focusing on the role of working-class women in the labour movement.

The strength of this section is the depiction of working women as agents of history, taking a significant role in the labour and trades union movement, from the female Charter associations of the 1830s and the Bryant & May matchwomen strikers of 1888 to the women machinists at Ford in Dagenham in 1968.

She brings the story up to date, looking at women workers and women’s rights today, concluding that, despite some gains, there is still much to fight against. In particular, the feminisation of poverty is growing apace and exacerbating the super-exploitation of working-class and black women. She calls for a reinvigorated trade union movement to tackle sexism and racism head on and take up the struggle for wage equality.

In conclusion, Davis turns her attention to women and the Communist Party, focusing on history, policy and perspectives. She includes the text of the historic resolution on women and gender, passed by the 55th Congress of the CPB in London in November 2018, which commits party members to defend and promote women’s sex-based rights and develop a branch education programme to disseminate understanding of the relationship between oppression and exploitation in Britain and around the world.

A superb book, it is to be hoped that it will form the basis for political education across the labour movement as well as bringing new women members – like myself – to the party. It concludes with the Charter for Women, which identifies broad-based campaign goals in three sectors – society, work and the labour movement.

The aim is to “ensure that by these means women’s collective demands are not only heard but acted upon.”

The strength of this work is in surveying and critiquing both the theory and history of women and class and in identifying what still needs to be done by way of analysis and practice in clear and accessible terms.

Although well organised, with accompanying illustrations of labour movement figures and activists, a criticism that could be made is of the book’s production — the typeface is cramped, faint and difficult to read, at least for this short-sighted reader. More generous margins and font size would have made this a more user-friendly publication.

That minor criticism aside, this is a compact and absolutely indispensable read.

Available from the CPB online bookshop, shop.communistparty.org.uk. There will be an online book launch and panel discussion of Women and Class, organised by the Marx Memorial Library and Workers School, with Professor Mary Davis, Professor Selina Todd and Dr Sonya Andermahr at 7pm on Tuesday September 29. Register at Eventbrite: eventbrite.co.uk/e/120007225843