This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THIS compact exhibition packs a potent aesthetic punch. All the principal Cubists are represented, with work that allows a full appreciation of the movement that shook and shaped 20th-century art in all its diverse strands.

With the world in rapid flux, Cubism burst onto the scene around the turn of the 20th century. It challenged established but tired post-Renaissance canons with canvases that communicated simultaneous viewing of the subject from different perspectives.

As an extra dimension, this approach factored in time lapses, with the artist shifting angles of viewing and recording. It also marked the first time pure abstraction was articulated on canvas, particularly by Lyubov Popova.

But it was Paul Cezanne who had laid the groundwork by “treat[ing] nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere and the cone” and then Pablo Picasso literally shattered all sensibilities — including George Braque’s — with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Soon Picasso and a converted Braque found new disciples and accomplices in Fernand Leger, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Jean Metzinger, Juan Gris, Auguste Herbin and others. Beyond the Paris bubble, Cubism rapidly gained momentum internationally, particularly in the Soviet Union, where it chimed with the revolution’s aim of overhauling a feudal society — a process that necessitated new aesthetics.

Adapting to national circumstance, Cubism morphed into Futurism in Italy, Vorticism in Britain and Suprematism and Constructivism in the Soviet Union.

According to French philosopher Henri-Louis Bergson, time is an incessant blending of past, present and future, and intuitive responses are superior to rational ones. That was in tune with Cubism, which “snapped” a reality in flux with an optic so unsettling as to be liberating. Modernity was unceremoniously ushered in.

Braque was the Cubist par excellence, with his style “reducing everything, places and figures and houses, to geometric schemas, to cubes,” according to one critic, who described his smaller paintings as “cubic oddities.” The definition stuck despite the obvious fact that cubes rarely made an appearance anywhere.

“Art is made to disturb,” Braque declared, adding that what matters in art is “the thing you cannot explain.”

According to Picasso, “Cubism is not a reality you can take in your hand. It's more like a perfume, in front of you, behind you, to the sides, the scent is everywhere but you don’t quite know where it comes from.”

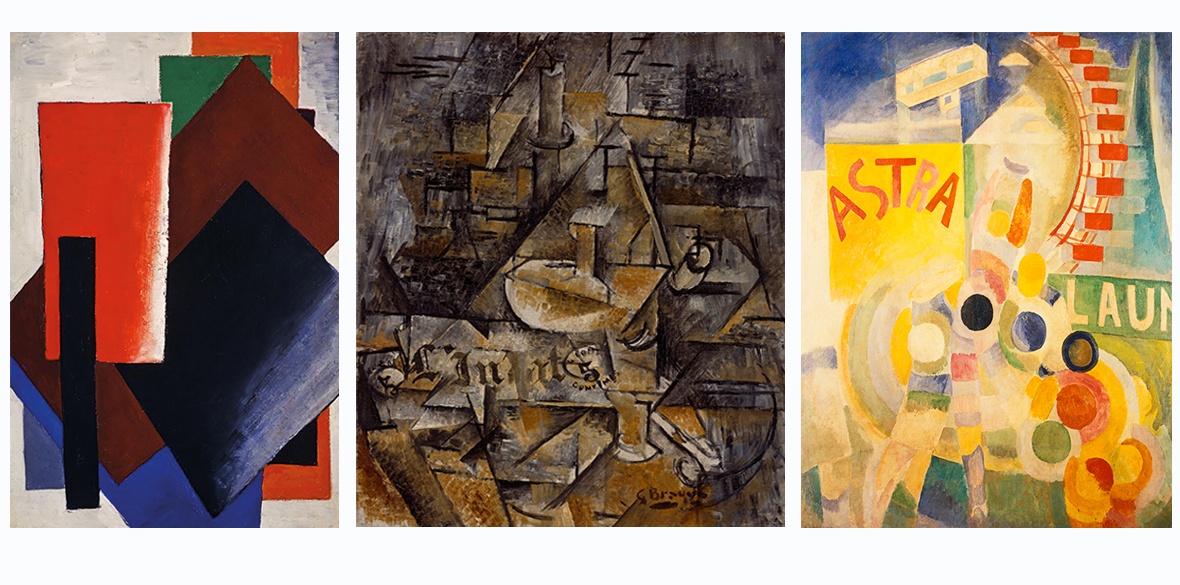

This exhibition offers a fascinating glimpse of the variety of individual styles or interpretations of Cubist principles, from the “shattered glass” perspectives pre-eminent in Braque’s The Candlestick of 1911 to the spatial shapes in Popova’s Painterly Architectonics of 1916, influenced by Kasimir Malevich.

Robert Delaunay’s The Cardiff Team of 1912 depicts a Parisian Ferris wheel, an “Astra” advertising billboard for an aircraft construction company and, in the top-right corner, the Eiffel Tower — the ultimate symbol of modernity.

Like Guitar, Gas-Jet and Bottle, Picasso’s collage of painting and drawing, it amalgamates different fragments of reality into a compelling visual synthesis.

The work on show emanates an exhilarating sense of quest and joy at repurposing art as a tool of optical discovery, made easier by the traditional themes of landscape, still nature or portraiture.

Free exhibition which runs until October 4. Advance booking required at nationalgalleries.org/exhibition/cubism