This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

HOW should histories of great violence, which have undoubtedly shaped the contemporary world, be represented in art — literary or other? Is there a limit to what can or should be depicted?

Behind these questions is the issue of how and why we should read literature that asks us to consider the perspective of the perpetrators and not the victims?

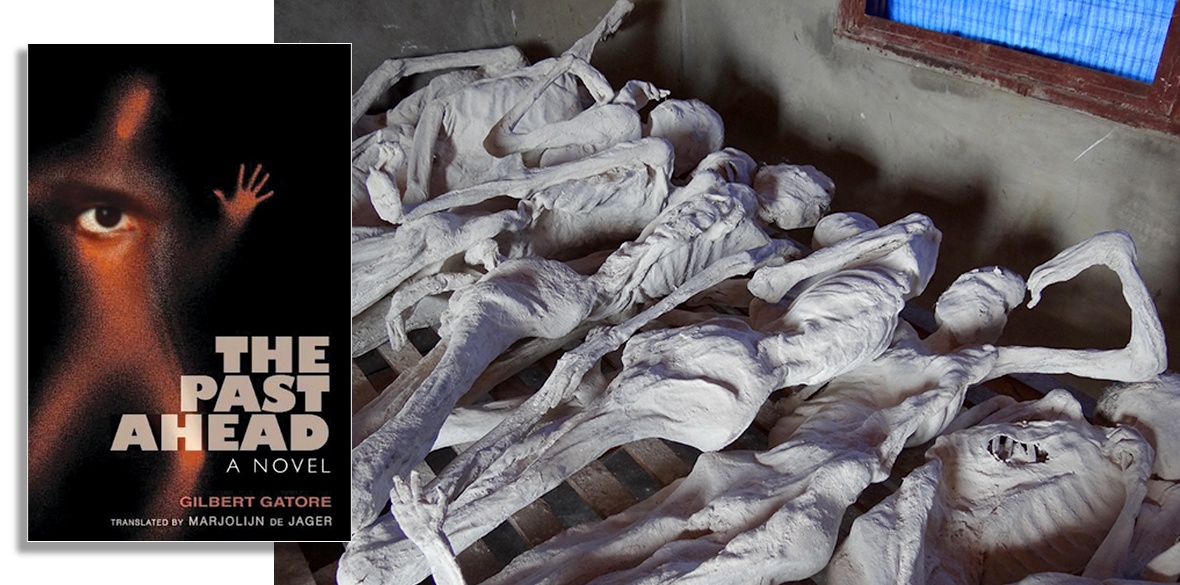

In 2008, Rwandan author Gilbert Gatore published his first novel The Past Ahead.

Born in 1981, Gatore was only a child when the genocide in Rwanda erupted. He fled with his family to neighbouring Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). At the age of 16 he arrived in France, where he has lived ever since.

Gatore published The Past Ahead when he was 26 years old. He has said that the novel was partially inspired by his desire to reconstruct the content of a diary he had kept in Rwanda, but lost on the roads of exile.

It is significant for several reasons. First, it is one of the first to be written by a Rwandan who actually lived through the genocide. Literature written by Rwandans on the genocide had favoured the testimonial form until fairly recently. This is understandable. Their questions were too pressing, too anchored in reality, to harness the imaginary excesses of novelistic creation.

A second distinguishing characteristic of The Past Ahead is Gatore’s decision not to use terms that have become inseparable from the genocide in Rwanda: genocide, Hutu, Tutsi, and even Rwanda.

Yet there is no ambiguity about the historical episode being portrayed. The missing terms are replaced by others: civil war, massacres, killings, barbarians and moles. The novel distinguishes between those who are “on our side” and the “pays … la ou” (country … there where).

A third feature of The Past Ahead undermines the binary distinction between perpetrators and victims, weaving together the stories of two protagonists.

The first, Isaro, returns to Rwanda, where all her family were massacred, to document the genocide, interviewing witnesses, survivors and perpetrators.

The second, Niko, is a figment of Isaro’s imagination: a mute social outcast who participated in the massacres, then withdrew from society indefinitely.

Gatore does not shy away from detailing Niko’s crimes, but the reader cannot help but feel sympathy and even compassion for young Niko.

This representation was, for some, neither tolerable nor realistic. It established what literary critic Catherine Coquio called a pacte pervers (perverse pact) between the author and the reader.

Some critics have reproached Gatore for writing a genocidal character for whom the reader develops sympathy in order to expunge filial guilt concerning Gatore’s own father, who was accused of participating in the genocide.

Gatore must have known that his novel was likely to provoke strong debate. He opens The Past Ahead with a warning: “Dear stranger, welcome to this narrative. I should warn you that if, before you take one step, you feel the need to perceive the indistinct line that separates fact from fiction, memory from imagination; if logic and meaning seem one and the same thing to you; and, lastly, if anticipation is the basis for your interest, you may well find this journey unbearable.”

The Past Ahead muddies the waters between history and stories, making it impossible for some to see this novel as a work of fiction, rather than a manipulated version of history.

Parallels can be drawn with Der Vorleser/The Reader (1995) by German writer, philosopher and judge Bernhard Schlink.

The Reader recounts the story of Hanna Schmitz, a German woman who is accused and convicted for her role as an SS guard under the Third Reich.

Schlink presents Hanna’s illiteracy as a mitigating factor. The reader indeed feels empathy for her, identifying redeeming traits in Hanna that stand in stark contrast with her terrible actions.

George Steiner, an influential literary critic and a Holocaust survivor, described Schlink’s novel as both “profoundly moving” and “rapidly becoming a touchstone of moral literacy.”

Others have not been so complimentary. Jeremey Adler, himself the son of a Holocaust survivor, denounced the novel as an exercise in “the art of generating compassion for murderers.”

No-one could accuse Schlink of defending the Nazi regime. His own father, a professor of theology and a pastor in the Confessing Church, was a victim of Nazi persecution. Neither Gatore’s nor Schlink’s protagonists remain indifferent to what they have done.

But many of the accusations of historical revisionism levelled against their novels have arisen from the ways in which the subjective memories of the protagonists do not align with the accepted history.

This divide between subjective memory and objective history has proved to be central to the critical reception of genocide literature.

Yet the division is problematic. For historian and scholar Enzo Traverso, the distinction between history and memory is an illusion, as history is itself a narrative process of selection: “We need to take into account the influence of history on memory itself, for there is no such thing as a literal, original and non-contaminated memory: memory is always constructed within public space, and therefore subject to collective modes of thought, but also influenced by the established paradigms for representing the past.”

But the dichotomy between subjective memory and objective history does not reflect the complexity of personal and collective representations.

The distinction between victim and perpetrator is often oversimplified; it cannot account for all the nuances of responsibility. It is precisely within literary texts that these complexities can be revealed.

This is not to say that perpetrators and victims do not exist, both in history and in fiction.

It is, however, to recognise that literature is a “safe” space where conventional categories — memory and history, victimhood and guilt, damnation and redemption — can be tested and negotiated. This is the great value that sets these texts apart from purely historical accounts.

The flexibility of literature plays a fundamental role in the cultivation of empathy, comprehension and forgiveness, the very emotions that are absent from the violent histories of our world.

It can render the incomprehensible slightly more comprehensible and, in doing so, underscore the humanity of all.

The potential for works of fiction to make us think deeply about how we treat others, about the decisions we make and the judgements we pass far outweighs critical condemnation on the basis of accurate or immoral representations.

Readers do not have to agree with an author’s fictional portrayal, but they should defend the right to portray.

Charlotte Grace Mackay is lecturer in European languages (French) at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. This is an abridged article republished from theconversation.com under a Creative Commons licence.