This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

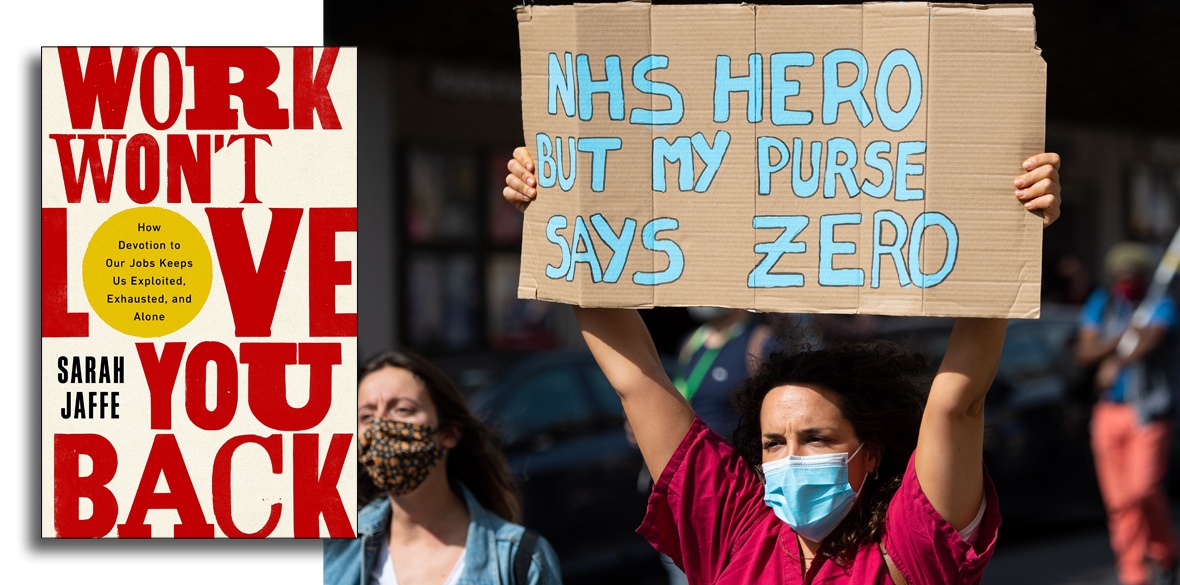

Work Won’t Love You Back: How Devotion to Our Jobs Keeps Us Exploited, Exhausted and Alone

by Sarah Jaffe

(Hurst, £20)

A WHOLE new lexicon emerges from this compelling overview by Sarah Jaffe — Americanisms like “hope labour,” “work to labour,” “grunt work,” “fauxtomation,” “crunch work” and “fampany” symbolise erosions of human status in the system of production.

Beginning with family — the domain of women’s unpaid reproductive labour since forever — Jaffe shows how the model of unacknowledged “love” work has been co-opted by business to serve, obscure and promote exploitative profit-making.

The ideal of the compulsively motivated, long-hours marathon worker, resilient and unquestioning in pursuit of her organisation’s objectives, is one pedalled through business schools and institutes. Jaffe shows how a feminisation of work has evolved in which exploitation must be felt as fulfilment and precarity welcomed with a kind of Stepford Wives ever-ready smile.

Stepping outside the unpaid labour of home to the barely paid of care work has been a female progression. Low-paid care for those at every stage of life is women’s work and Jaffe shows how a devaluing of emotional labour supports the low-wage market.

UN researchers estimated in 1999 that women’s unpaid reproductive labour amounted to $11 trillion worth of a $16tn total. Women’s work through the pandemic has vastly increased such figures.

Internship is our age’s gateway drug to job dependency and Jaffe shows how “work to labour,” the unpaid slog to launch careers, has become a more permanent gig. “Hope labour” is the belief that we will eventually land that great job if only we can endure long periods at the subcontractual or non-contractual fringe.

Increasingly, subcontracts are what pass for employment agreements, with single-use, disposable workers becoming more explicit as corporate policy. Introducing a new wage floor — free — into the system allows companies to substitute interns for entry-level workers, revealing “hope labour” as a snake eating its own tail.

Jaffe shows universities acting as clearing houses for unpaid work through their internship programmes. The corporatisation of universities by privatisation sees tenured positions crumble, with low-paid, part-time visiting or adjunct lecturers carrying the burden of increased student “throughput.”

Exploitation, feminised, is shown to be floating the tech boat too. Underlying the fantasy of start-up labours of love, pleasure-principled creative play or boyish genius, is the reality of “crunch,” defined as excessive unpaid overtime for tech outfits self-identifying as “fampanies.” “

“Vampanies” more like — playroom architecture, in-house catering, gamification of grunt work — all seek to extract more value from employees and blur the delineation of work, private space, home and family.

Throughout this valuable account, Jaffe makes the case for unionised organisation as the only way to take back control and she gives many examples of US workers fighting to form unions and winning.

“Work no longer works,” she concludes. Convincing us that work is our greatest love, Jaffe finds, is capitalism’s greatest trick. Unionisation offers a revaluing of ourselves and others.