This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THROUGHOUT post-classical art, there’s a venerable tradition of male erotica hiding in plain sight.

Michelangelo’s David, Fabre’s Death of Abel and numerous scantily clad — if a little punctured — Saint Sebastians, to name but a few, indulged homosexual desire as much as they conveyed religious sentiment, and often more so.

For the most part, these works were only ever gazed upon by an elite, privileged few. But, as John Berger pointed out, mass-production democratised the image as much as the printing press did the written word.

Thus, in the 1950s and 1960s — when homosexuality was met with extreme hostility and prosecutions for sodomy or gross indecency were commonplace — gay and bisexual men could at least enjoy the male form, without fear of reprisal, by purchasing an art magazine or “beefcake” title.

Published, ostensibly, to promote fitness, athleticism and the purely aesthetic appreciation of the body, publications such as Demi-Gods, Mr America and Adonis were full of men wearing nothing but G-strings, posing languorously beside swimming pools or engaged in strenuous physical activity.

Containing no overt “homosexual activity,” they obeyed censorship laws and could be widely distributed from newspaper stands, bookshops and through mail-order subscriptions.

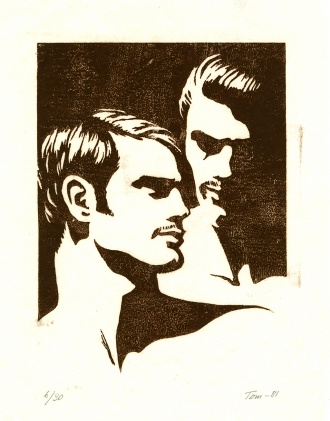

Illustrations were published too and one such magazine, Physique Pictorial, launched the career of Finnish artist Touko Valio Laaksonen (1920-1991). A major exhibition of his work, scheduled to open last month at London's House of Illustration, has been postponed cue to the Covid-19 pandemic.

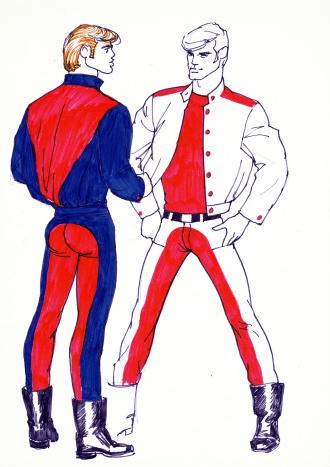

His hyper-masculine creations — all of them tall, spectacularly muscular and comically tumescent — not only spoke to readers’ fantasies and desires but allowed them to briefly glimpse a world where homosexuality was celebrated with cheerful abandon.

“In those days, a gay man was made to feel nothing but shame about his feelings and his sexuality,” said Laaksonen. “I wanted my drawings to counteract that, to show gay men being happy and positive about who they were.”

He originally signed his work “Tom,” to maintain anonymity, and the magazine’s editor Bob Mizer sought to heighten Laaksonen’s mystique, suggesting that the moniker Tom of Finland would provide the north-American readership with a perfect mixture of wholesomeness and exoticism.

He may have been right. Tom soon developed a healthy mail-order business from his home in Helsinki, sending cartoons via airmail to avoid arousing the suspicions of customs officials.

So exquisitely paranoid were obscenity laws in the US that they not only banned the depiction of physical contact between two men, unless they were wrestling or fighting, but anything deemed sexually “suggestive.”

But with Tom clearly seeing these restrictions more as creative parameters than artistic prohibitions, the joke was on them. He relished the opportunity to push the envelope of what was legally permissible and triumphed in obeying both the letter and spirit of the law, often quite literally, drawing soldiers, sheriffs, policemen and prison guards engaging in sexually charged violence towards men under their control.

These images, often a sequence in narrative form, are, for sure, morally ambiguous. But, as well as throwing the law’s warped priorities into sharp relief, it’s tempting to think of their surprising conclusions — a merry display of camaraderie between all involved — as Tom’s way of raising a middle finger to the powers that be.

Though US beefcake magazines were happy to publish drawings that — forgive me — cocked a snook at prevailing sexual norms, they were less inclined to print work that challenged racial prejudice, refusing Tom’s exceedingly modest sketches of inter-racial couples.

But in Britain at least these were well received by certain circles and he developed an enduring attachment to London, in particular the Sixty-Nine Club, Europe’s oldest social group for gay leathermen.

Tom was clearly fond of the familiar archetypes of sailors, lumberjacks, bikers and policemen in the roster of homosexual fantasy and they frequently appeared in his work: not-so-subtle ripostes, perhaps, to the depiction of gay men in popular culture as emasculated degenerates.

If he sought to banish one form of shame from gay life however, he actively encouraged another through his elision of sexual liberation and desirability with Herculean magnificence.

“My aim is not to create an ideal but to draw beautiful men who love each other and are proud of it,” he maintained. Fair enough, but emancipation requires a wider degree of latitude from beauty, and a cursory glance at Instagram these days would suggest otherwise.

The House of Illustration is closed at the moment, but these images were never really intended for a gallery’s formality and the sense of permanence it bestows.

Part of their appeal, and much of their power, lay in their vulnerable impermanence: in the knowledge that the censor — be it the state, or an overzealous parent — was never very far away.

Created before the internet democratised the image to a staggering, sometimes frightening, degree and before the smartphone effectively completed our transition into passive consumers and narcissistic objectifiers, it isn’t their boldness which draws the eye so much as their innocence.

Tom of Finland: Love and Liberation is scheduled to run until September 20 when the House of Illustration reopens. Details: houseofillustration.org.uk.