This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

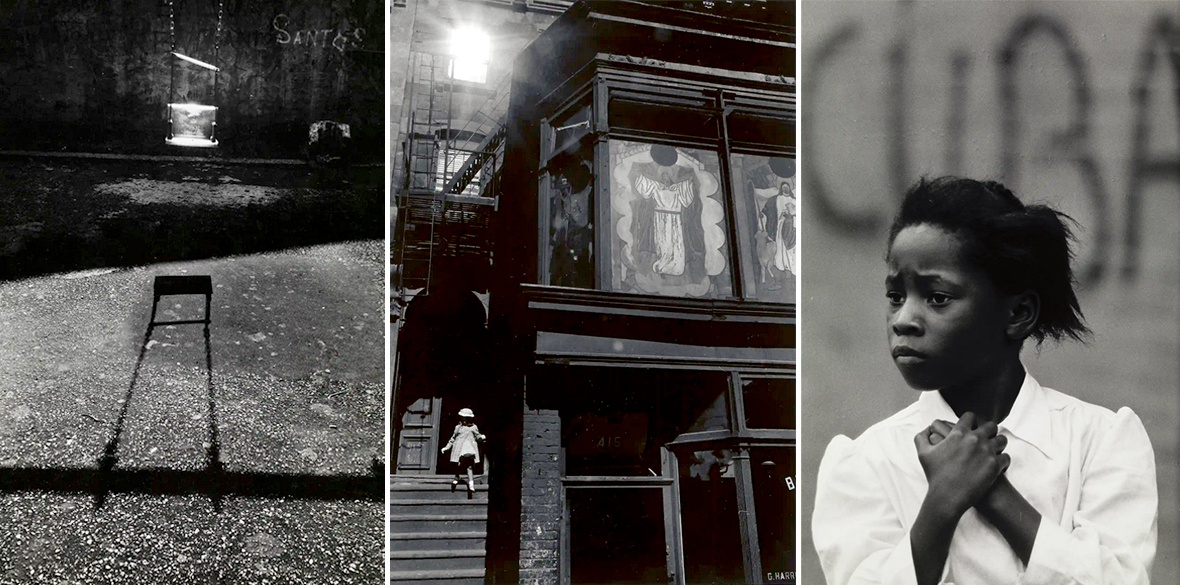

Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

BLACK photographers have been largely ignored by the mainstream media both here and in the US, so it is particularly welcome that this online virtual tour of the exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) is a reminder of what a powerful contribution to the art of photography such individuals have made.

Working Together features more than 150 photographs by Louis Draper and other members of the Kamoinge Workshop, a photography collective he helped found in New York in 1963, and he became one of its chief mentors.

On show are valuable documents and publications related to the formation of the collective and this exhibition explores the impact of this remarkable group of African-American artists on the history of photography in the latter part of the 20th century.

Inspired by the archive of Draper from Richmond in Virginia, Working Together focuses on the workshop’s first two decades and features the work of more than a dozen members who joined between 1963 and 1972. They were largely men but did include several notable women photographers.

These photographers found they could get little work in the mainstream, white-owned media and were very unhappy about the portrayal of the black community in it.

They took the name Kamoinge — “a group of people acting and working together” in Kikuyu — from a book by Jomo Kenyatta.

In the early years, it operated as a formal group that voted on membership and recorded attendance, yet when asked what Kamoinge means to them now, nearly every member from that early period stresses that it became a sort of surrogate family.

While the artists maintained independent photography careers, they met weekly to show each other their work and engage in a lively exchange of ideas.

They stress, though, that their work at the time was not so much political as a reflection of the rich cultural life of their fellow black citizens.

They organised exhibitions, produced portfolios and mentored youth.

Although their philosophy would change as the struggle for black emancipation and equal rights grew, Draper describes how many of the group had been a part of the March on Washington with Martin Luther King.

Others had witnessed southern law brutality brought on by voting-rights activity and sit-ins.

“Within a year’s time, these same volatile forces had propelled many of them into engaged and enraged resistance,” Draper says.

Kamoinge helped shape a critical era of black self-determination in a period that coincided with a pivotal shift in photography’s wider acceptance as a powerful artistic medium and tool of social commentary.

No exhibition can fully recreate the complexity of such a large and interconnected group, yet Working Together highlights some of the visual dialogues among the members’ photographs, while using archival material to trace the group’s significant exhibitions and publications.

The group organised several shows in their own gallery space, in addition to exhibitions at the Studio Museum in Harlem and the International Center for Photography.

They were also the driving force behind The Black Photographers Annual, a publication founded by Kamoinge member Beuford Smith, which featured the work of a wide variety of black photographers at a time when mainstream publications offered them few opportunities.

One member, Roy DeCarava, collaborated with poet Langston Hughes on his 1955 book The Sweet Flypaper of Life and it became a touchstone for Kamoinge members.

Beyond their aesthetic influence, the book’s photographs expressed DeCarava’s commitment to making images of the African-American community.

Cognisant of the forces for change revolving around Kamoinge, members dedicated themselves to speak of their own lives as only they could.

It was their story to tell and they set out to create the kind of images of their communities that spoke of the truth they themselves had witnessed and as a counter to the untruths in most mainline publications.

Part of their resistance was to make images of African-Americans absent from the national conversation.

Some members photographed leading figures and pivotal events of the civil rights movement, others street life in Harlem or portraits of black teenagers.

Many of their images engaged with the theme of civil rights symbolically and the exhibition includes a number of striking images from the great March on Washington.

This exhibition is a powerful record not only of the artistic abilities of these talented photographers but, perhaps more importantly, of a historical period of oppression, discrimination and inequality that one hopes is slowly being overcome.

Images available for viewing online at vmfa.museum/exhibitions/at-the-museum.