This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

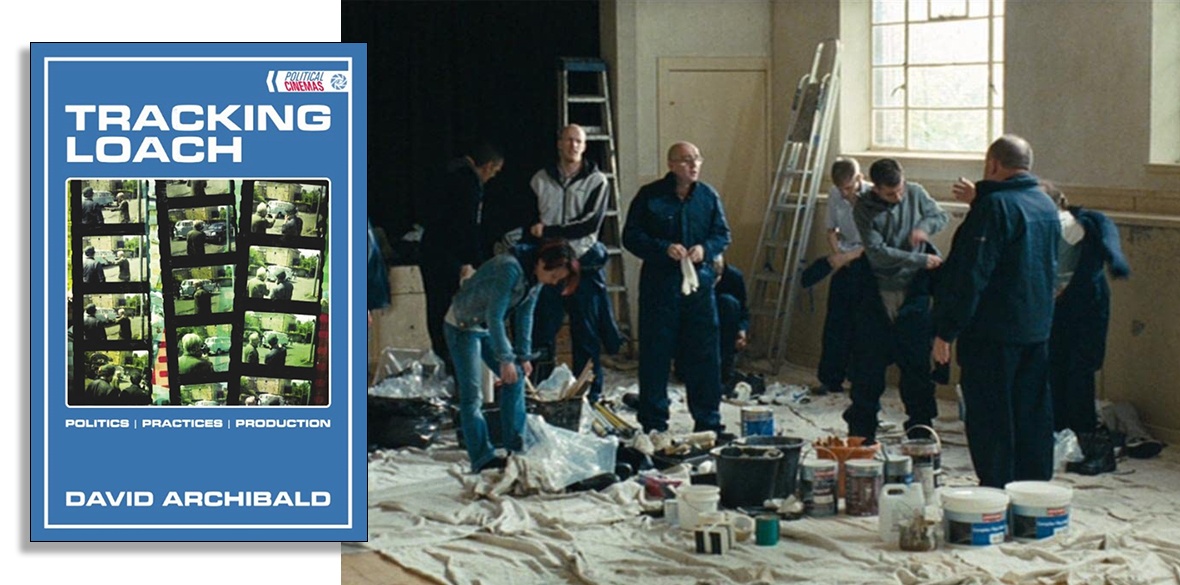

Tracking Loach

David Archibald

Edinburgh University Press, £19.99

DAVID ARCHIBALD’s book, Tracking Loach, is an academic celebration of Ken Loach’s 60-year career in socialist filmmaking and political activism.

It is also an extremely timely publication in that Loach’s latest film, The Old Oak, will be receiving its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival 2023.

The author’s unique approach is to prioritise the contextual mechanics of film production studies over the theoretical speculation of critical screen studies, arguing that observation of the methodologies and logistics involved in preparing, shooting and exhibiting a feature film should elicit a complementary understanding of a filmmaker’s aesthetic.

This reminds me of a television interview with David Niven from the 1970s where he asks something along the lines of: “How can a critic write a decent review if he’s never actually made a movie himself?”

During Archibald’s ethnographic pursuit of Loach’s poetic and political process his primary sources of data are the annotations, interviews, shooting documents, digital footage and photographs he accrued while being physically present during the production and exhibition of Loach’s working-class comedy-drama set in Glasgow, The Angel’s Share (2012).

It should be noted that to be granted access to such a complex and sensitive creative environment and its extremely busy and anxious workforce – its technicians and performers – and, in turn, to enjoy the company and trust of its leaders who have the weight of a major production bearing down on them – Ken Loach (director), Paul Laverty (screenwriter) and Rebecca O’Brien (producer) – is a memorable achievement in itself.

To accompany him on his journey the author also draws on a wide variety of historical and theoretical secondary sources, including the BFI’s Ken Loach Archive, and I personally found a number of his scholarly citations to be just as illuminating as his on-set observations.

For example, when working alongside his early screenwriting partner, Jim Allen, Archibald highlights that Loach’s television productions in the late 1960s and early 1970s were influenced by the political ideas of Leon Trotsky insofar as the UK’s established democratic system was seen to be inadequate with regards to the economic interests of the proletariat.

Following on from this it is argued that Loach’s films generally aim to reveal to the audience, either explicitly or implicitly, the harsh realities, exploitation and despair of working-class experience and, in turn, that capitalism is not a natural, normal or inevitable way of ordering or governing society.

With this in mind the socialist concerns of Loach’s oeuvre have generally transitioned from addressing issues such as organised labour in The Big Flame (1969) and The Rank and File (1971), to unorganised labour in Riff Raff (1991) and The Navigators (2001), and then on to unemployed labour in Sweet Sixteen (2002) and I, Daniel Blake (2016).

While such films could be viewed as a war artist’s mournful depiction of socio-economic casualties lying strewn across a neoliberalist battlefield, Archibald posits with reference to the Italian historian, Enzo Traverso, that they can also be understood as evidential “open wounds” which the left needs to nurse so the embers of possibility can once again be reignited.

Aware of Raymond Williams’s contention that “to be truly radical is to make hope possible, rather than despair convincing,” the author proceeds to cite Newland and Hoyle’s view that in some ways Loach’s creative output in the 21st century has begun to move away from the wholly melancholic art cinema of, say, My Name Is Joe (1998), and on towards the Ealing comedy tradition with films like Looking for Eric (2009) and The Angel’s Share (2012).

Indeed, as Loach himself states in a footnote: “Not every film has to end with a fist clenched in the air.”

Loach is a social realist director with the eye of a sympathetic documentarian, influenced by, amongst other things, Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop, the Free Cinema Movement and the 20th century current affairs programme, “World in Action.”

Moreover, similar to the generic conventions exhibited in films from the Italian neo-realist movement such as Rome, Open City (1945) and The Bicycle Thieves (1948), Archibald frequently underscores Loach’s overarching quest, paradoxically, to recreate spontaneity, authenticity and “truth” in his fictional work by employing predominantly naturalistic filmmaking techniques.

By shooting on a “real” location instead of within an “artificial” studio Loach’s objective is to not only encourage the actors to respond to their surrounding environment like recognisable, everyday human beings, but to also display the historical power relations which are inscribed into, for example, the municipal buildings which overshadow them.

Echoing John Grierson’s principle of “actuality,” Loach tends to shoot static medium long shots with the filming apparatus and its crew as far away from the “action” as possible, a tactical attempt to motivate the audience to decide what is important and what to focus on, as if they themselves are simply observing matters from across the street.

In turn, this sense of things “really happening” is often reinforced by natural lighting during a shoot via the sky for exteriors or windows for interiors, and by way of continuity editing in post-production so as not to “interfere” with the actors’ on screen performances and the linear story they are striving to tell.

Of course, to achieve “the illusion of the first time” casting is crucial, and Loach’s production team frequently enlist non-professional or amateur actors as a consequence. David Bradley as Billy Casper in Kes (1969), Crissy Rock as Maggie Conlan in Ladybird, Ladybird (1994) and Martin Compston as Liam in Sweet Sixteen (2002) are just three notable examples.

An important factor in this process is, unlike most other independent British production companies, Ken Loach and Rebecca O’Brien’s Sixteen Films has become well financed and self-sufficient over the decades and so, as a result, they have the time to carry out lengthy scouting missions in order to locate and secure the right actor for the right role.

Of course, critics will argue that the casting of non-professional actors undermines the history and craft of acting, the experience involved, the knowledge accumulated, the techniques learned, the talent nurtured.

While this may be true, a reasonable response would be: what other practical routes are there available in the UK for the working-class to climb up on to the silver screen and represent their identities, communities and histories fairly?

In an industry predominantly based in London and owned, run and populated by the middle class and their superiors, the costs involved to train as an actor are astronomical to an ordinary person and the distance to travel, particularly for those in the north, preposterous.

In light of these socio-economic and ideological realities, Loach’s casting of non-professional and amateur actors – together with the working-class stories he tells and the working-class worlds he creates – should be regarded not simply as an aesthetic choice or even socialist posturing. That is, under the stifling, reductive right-wing administration we are all currently enduring in the UK, enabled on a day-to-day basis by numerous obsequious and self-serving cultural institutions and organisations, it could be reasonably argued that such an approach is a revolutionary act.

In his epilogue Archibald includes an apposite quote from the Spanish filmmaker, Luis Bunuel:

“A writer or painter cannot change the world but they can keep an essential margin of non-conformity alive. Thanks to them the powerful can never affirm that everyone agrees with their acts.”

In Tracking Loach there is so much to discover from its unique, rigorous and heartfelt exploration of one of the maestros of modern British cinema and modern British politics.

It is highly recommended.

Brett Gregory is the writer/director of the critically acclaimed, multi award-winning working-class feature film, ‘Nobody Loves You and You Don’t Deserve to Exist’ (2022).

This is an abridged version of a review that previously appeared in Culture Matters.