This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

BORN in 1881 in a Spain both conservative and Catholic, Pablo Picasso was first taught art at the aged of seven by his bourgeois art professor father.

It was an education in the rigid academic manner, also perpetuated at the art academies he attended in Barcelona and Madrid in the late 1890s.

Soon rebelling against this dominant aesthetic’s rigid orthodoxies and attendant bourgeois strictures, Picasso escaped into Barcelona’s bohemian, anarchist circles. He first visited Paris in 1900 — then the centre of the Western art world — and alternated between the French capital and Barcelona until 1904, when he settled in France to the end of his life.

He claimed the freedom to use a dizzying plethora of styles and mediums, including Expressionist and Surrealist distortions, Neoclassicism and occasional forays into naturalism, sometimes combining these.

Picasso’s Blue Period paintings were his first departure from academic styles, an example being The Old Guitarist of 1903, with their attenuated limbs painted in cool blues, lilacs, greens and greys. They express the pathos of the vulnerable, precarious lives of his neighbours in Montmartre.

But his invention of Cubism with Georges Braque from 1907 on was the most seminal and influential departure, to the point that other artists ignored it at their peril.

Shattering their subjects and the space around them into small, interacting facets, the two artists rebuilt them into images which echo the complex and fluid act of seeing, with its numerous, shifting viewpoints.

Paintings like the Seated Nude of 1909-10, on show at London’s Tate Gallery, challenged the static, fixed viewpoint perspective which had reigned in Western art since the Italian Renaissance. More than a new style, Picasso and Braque discovered a new visual language for the new century.

Picasso refused to be limited by any single style, yet he never painted a totally abstract work, despite abstraction being claimed as the most advanced style by leading critics. Why ? Because for him, styles were never an end in themselves but a range of means from which to express differing responses to different subjects.

He was, he said, motivated by the “joy of discovery and the pleasure of the unexpected.” His subjects were traditional and there were a few but important history paintings — Guernica being the best known — and portraits, female nudes, still lives, landscapes and scenes of everyday life. But he gave these subjects contemporary relevance.

Many works celebrated daily life, be it a bird, a man carrying a goat, a mother overlooking her children drawing or his lover Marie-Therese reading.

Sex features large as a symbol of procreation, pleasure and occasionally of aggression. Some have accused him of being obsessed by sex but this focus can be understood as challenging contemporary moeurs which forbade public frankness about such a normal part of life.

Picasso was truly politicised by the Spanish civil war from 1936 to 1939. By then, he had an international reputation as a leading modernist artist and he used this status to voice public support for the fledging republic, including accepting its commission of a mural for its pavilion at the 1937 Paris World Fair.

That he chose to expose the Luftwaffe’s aerial destruction of the helpless town of Guernica was a political act. Its cubo-expressionist depiction in sombre black, grey and white of the agonised screaming women and the terrified horse, overseen by an impassive cruel bull, has become an enduring symbol of outrage at war’s civilian victims.

Henceforth Picasso’s political engagement never wavered. Unlike most modernist artists, he defied the nazi occupation of Paris by staying there throughout WWII in solidarity with the French people. In 1944, he joined the French Communist Party, which had been a leading force in the Resistance, and he remained a committed member until his death.

During almost three decades he generously used his wealth and worldwide fame in public support of communism. In 1948, he gave the massive sum of one million francs to L’Humanite’s miners’ strike fund and he knowingly used his presence on peace demonstrations to draw press coverage for the cause.

Picasso read the party’s publications and its paper L’Humanite daily and he also created numerous designs and illustrations for posters, book jackets, scarves and other fund-raisers for the Communist Party.

He engaged in cultural debates with other artists and intellectuals, not least when attending the communist-organised peace congresses in Wroclaw in 1947 and Paris and Rome in 1949. He travelled to the Sheffield congress in1950, which was banned by the Labour government.

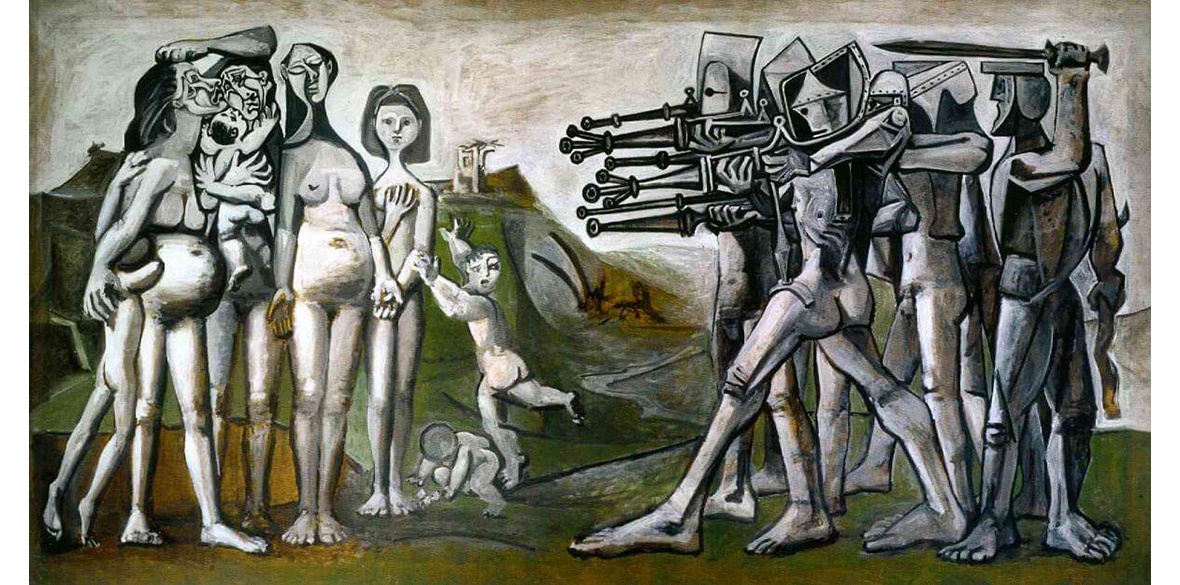

He rarely painted overt political content but the massacre in Korea of 1951 sprang from his visceral disgust at General MacArthur’s use of chemical weapons, an indictment which Picasso repeated in his murals War and Peace for the communist municipality of Vallauris.

“To search means nothing in painting. To find is the thing,” Picasso said and a profound humanism links his paintings, collages, prints, sculptures, assemblages,ceramics and graphic designs.

A truly extraordinary person, he relished the pleasures and joys of life while fearlessly indicting its cruelties and injustices.