This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

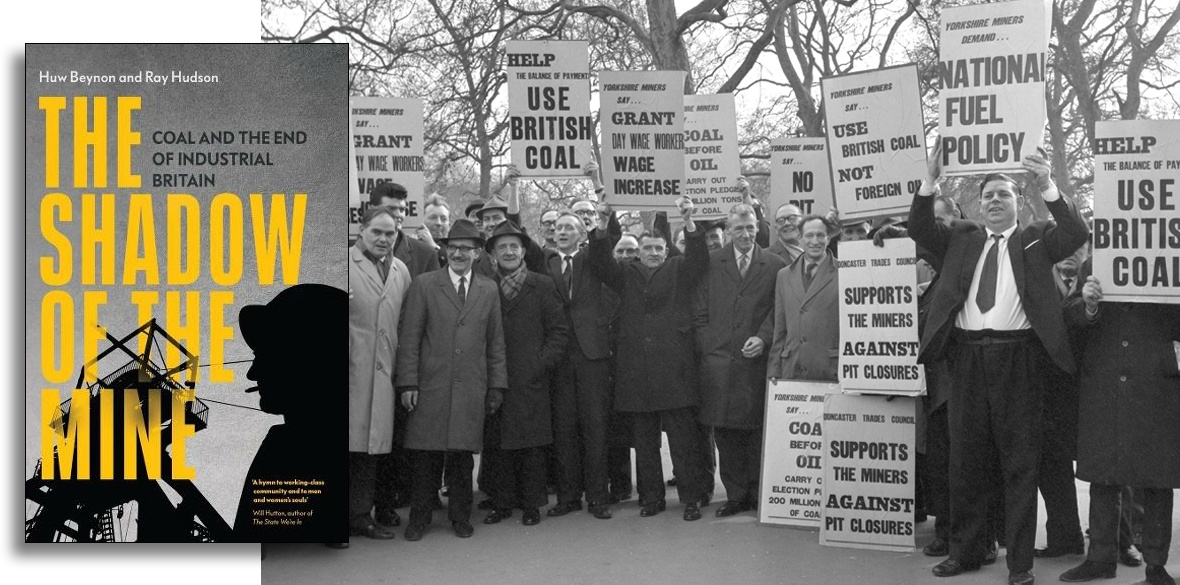

The Shadow of the Mine

Coal and the end of Industrial Britain

Huw Beynon and Ray Hudson

Verso £20

FOR anyone interested in the rise and fall of the British coal industry and its associated mining communities over the course of the 20th century, it quickly becomes apparent that there has been no shortage of books published on the subject .

And of those written from an overtly socialist perspective, it’s understandable and appropriate that there has often been an overt concentration upon the momentous events of 1926, 1972 and 1984 and on the strong, united and disciplined union movement central to them.

What then the need for yet another text?

In a sense, because a focus upon more dramatic periods has overshadowed equally significant longer-term developments or just enabled them to be ignored completely.

The Shadow of the Mine ably helps to fill some of these gaps — and a considered, comprehensive and insightful read it is too.

Rooting itself specifically in the experiences of the south Wales and Co Durham coalfields, it gives a geographical anchor to the narrative in a way that other purely national level accounts often lack.

It also demonstrates how not only did the mining industry differ radically from area to area but so too did the National Union of Mineworkers, something which might come as a bit of a shock to leftists who have often portrayed it as some sort of monolithic and timelessly militant organisation.

Its noteworthy how little attention has been paid to the nationalisation of the coal industry in the immediate post-WWII period.

While not falling for the ridiculously ultra-leftist line that this was a sideways step, Beynon and Hudson are at pains to point out that neither was nationalisation an unconditional victory.

Private mine owners were more than generously “compensated” for their loss and often went to take up key and well-paid positions in National Coal Board management.

Likewise, although nationalisation brought gains in health and safety and facilitated the extraction of coal on a more more scientific and technologically advanced basis, disasters both inside the pits (eg Six Bells Colliery, 1960) and outside (Aberfan, 1966) showed horrific limits to this, as did the emergence of preventable diseases such as bronchitis, pneumoconiosis, emphysema and white finger all of which continue to blight the lives of thousands.

It’s clear as well that there were immense restrictions on how much say miners and their representatives had in the development or otherwise of the coal industry.

This might seem obvious in the light of Margaret Thatcher’s and Ian Macgregor’s complete tearing up of the previously agreed upon national Plan for Coal, but it was the norm prior to this during the decades of the so called Keynesian social democratic consensus when the closure of huge swathes of the coal industry really began.

Far before Norman Tebbit’s heartless and cruel injunction that the unemployed get on their bikes in search of work, miners uprooted sticks and moved to coalfields that were seen as more productive for what they were told would be jobs for life, promises which were rarely, if ever, kept.

Throughout the book, Beynon and Hudson are keen to explore what life was like, and to a certain extent still is, in the pit villages of their chosen communities.

Proud of “their “industry, many defined themselves as mining communities and this was a label worn often as much by women as it was men.

Additionally, there was a clear and shared generational aspect to this, industrial action against redundancies often being undertaken on the basis that this was a way to secure employment for future generations as well as the present.

Identifying as miners didn’t mean people saw their lives beginning and ending at the pithead.

Often neither situated in either city or country, these “urban villages” built upon key institutions such as the miners’ welfare, union lodge, chapel and local pub created a myriad of social and cultural activities the likes of which we are unlikely to see again.

As moving as the film Billy Elliot might have been, had mining communities been as uninterested in culture as parts of it seem to argue, we’d had never seen the emergence of Marxist autodidacts like the late Mick McGahey, of artists like the Ashington Pitman Painters and of an unbroken tradition of brass bands which continue to thrive to the present day.

Politically, close involvement with the Labour and Communist parties meant that villages like Maerdy and Chopwell quickly earned the title of “Little Moscows.”

Self-policed, autonomous, family-oriented and hard-working it was sickening that many such villages eventually fell victim to a political party that claimed to espouse such values and even more of a shock that cracks in the traditional “red wall” led to constituencies such as Leigh voting in Tory MPs at the last general election.

Finally, a key and significant difference to this book is that it doesn’t leave the field after the crushing defeat after the miners in 1985 with a few pages documenting its heartrending after-effects.

There is, of course, attention paid to how key indices like levels of unemployment, mental illness and drug and alcohol abuse rocketed out of control, but just as importantly equal attention is given to other neglected areas such as changes in housing provision.

Equally, attempts are made to document both government plans to provide investment and jobs for the poorly co-ordinated, ineffective charade that they are and the continued efforts on the parts of communities to change this for the better.

Although the fight to keep the pits open might have ultimately failed, a determined and resourceful coalition has come together to fight for compensation for preventable industrial diseases, to campaign for truth and justice for the events at Orgreave coking plant and to continue to hold the ever well-attended Durham Miners’ Gala, which has now become the largest labour festival to be held across Europe.

Beynon and Hudson cover all of this and more in a book that deserves the widest of distribution.