This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

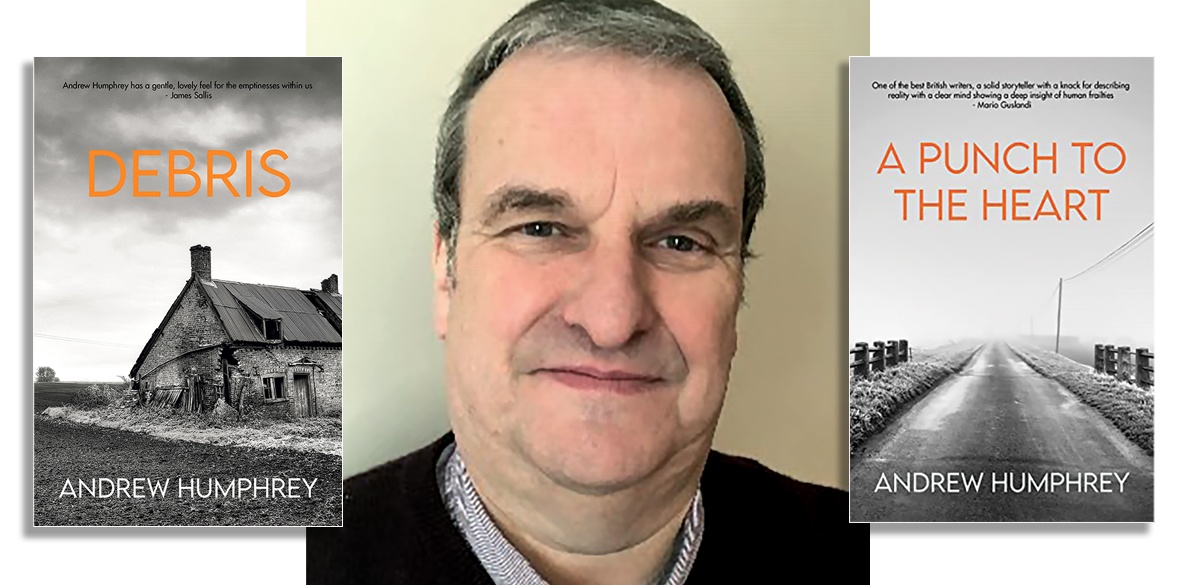

Debris

by Andrew Humphrey

Head Shot Press, Paperback, £7.99

ANDREW HUMPHREY is East Anglia’s best kept literary secret. In the noughties he produced two impressive story collections and a neonoir novel, Alison. Lauded for their elegant prose, psychological complexity, and vivid characterisation, his tales of horror, crime and the marginally weird garnered critical acclaim and a small but fervent audience. Then, to the disappointment of his admirers, Humphrey went off the radar for almost a decade.

So, the announcement of two new books from the recently launched Head Shot Press — a short novel and a story collection — was met with eager anticipation.

Debris, the novel, is an existential detective story concerning disaffection, deception and lives out of kilter. On the surface it is character-driven literary fiction, but the author’s experience of writing horror and crime has seeped into the narrative, so that run-of-the-mill experience is saturated with a sense of the strange.

The story unfolds from the viewpoint an unreliable narrator struggling to come to terms with his gambling, fractured relationships and history of embezzlement.

The protagonist, Nick, belongs to a literary tradition of mesmerizing but exasperating malcontents. His forerunners include Saul Bellow’s commitment-dodging Herzog, John Kennedy Toole’s misanthropic idler Ignatius J Reilly and David Gates’s self-destructive alcoholic, Jernigan.

The narrative focuses on the shifting relationships of a deftly drawn network of characters. These include Nick’s equally damaged brother, Patrick; Patrick’s ex-wife, Hanna, who now lives with Nick; and Jessica, Hanna’s younger sister and Nick’s former girlfriend. Finally, but significantly, there is Nick and Patrick’s vindictive, secretive and manipulative mother.

Nick’s life is an apparently doomed quest for connection and meaning. He staggers through a fallout zone of financial, sexual and emotional betrayal, where memory is malleable and truth provisional.

His alienation and moral confusion could stand as a metaphor for the absurdity of social relations under late capitalism, but this is not an overtly political novel in the “state of the nation” mould of John Lanchester or Jonathan Coe. Instead, Humphrey’s narrative considers interpersonal dynamics through an in-depth exploration of his characters’ inner lives.

His insights into the dark psychology of families, sex and betting shops are enlightening, original and profoundly unsettling. The seriousness of the story is never allowed to drift into solemnity: the dialogue fizzes with wit and there’s humour in some of the darkest moments.

A Punch to the Heart

by Andrew Humphrey

Head Shot Press, Paperback, £7.99

A PUNCH TO THE HEART is a collection of nine short tales about lies, misapprehensions and various forms of psychological isolation. There is considerable thematic overlap with Debris, but if Humphrey is obsessively ploughing the same furrow, he’s doing it with impressive style and variety.

Highlights include the collection’s longest story, Walk On By, in which a group of men meet at the funeral of Maggie, their former lover, and are confronted with her contradictions and ambiguities.

It becomes apparent that each of them knew a different version of Maggie and a few, including the narrator, set out to discover more about her life and death.

This tale of grief, loss and the difficulty of understanding other people, even those with whom we are intimate, is made all the more absorbing by Humphrey’s attention to the details of speech, gesture and the built environment.

Place is a vital aspect of Humphrey’s stories and novels. The buildings and landscape of Norfolk are so vividly rendered, and references to them so carefully embedded, they become auxiliary characters in his stories.

Bad Milk, concerns a conceited and vicious Tory politician and the hapless brother upon whom he inflicts a lifetime of systematic persecution. This bleak revenger’s comedy, the closest thing in the collection to a traditional satire, is deceptively nuanced and full of unexpected turns.

There’s another fraternal imbalance of power in Duck Egg Farm, a story of drug dealing, gangland violence and the voracious consumption of paperback novels. It captures the fear and boredom of organised crime and includes a metaphysical element.

In the hands of a lesser writer this collision of genres could have created an impenetrable mess, but this is terse, multilayered and bravura storytelling.

Humphrey has a flair for subverting expectations. This is evident in the web of middle-class snobbery, infidelity, confidence tricks and murder in Vinegar Lake; and in the dialogue with a therapist in Box, a story involving a dysfunctional family, controlling behaviour and masochistic sex.

In many of his stories, characters are not what they initially seem.

Many years ago, I described Humphrey as “East Anglia’s laureate of loss and alienation.” On the evidence of these new publications, that description holds true. I have no idea why he stopped writing fiction for a decade, but I’m delighted to learn he’s back in print.