This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

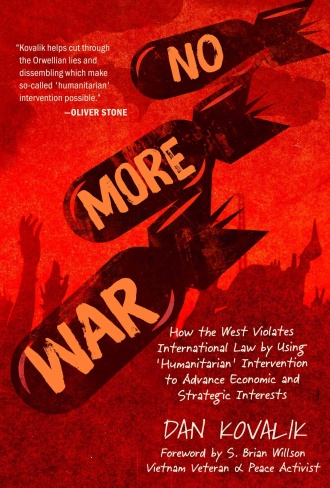

IN HIS latest book, Pittsburgh-based lawyer and peace activist Dan Kovalik is at pains to stress that the UN Charter, the principal instrument of international law since its signing in 1945, lays down a number of important precepts regarding humanity’s need for peace, equality and freedom from oppression.

Prevention of war is at its core, and states are to resolve disputes by peaceful means if these are available. An armed attack on one state by another can only be considered legal if, having exhausted all non-violent paths, the attack has been approved by the UN security council, or if it is carried out in urgent self-defence against an armed attack, or if the invading party has been granted consent by the leader of the host state.

As such, Kovalik demonstrates convincingly that almost every war waged by the US and its allies in the post-WWII period, including against Iraq, Libya, Yugoslavia, Nicaragua, Afghanistan and Vietnam, has been illegal under international law.

Thus the instigators of these wars must be considered war criminals, and it’s entirely reasonable to demand that they be prosecuted as such.

Kovalik notes that the commonly accepted definition of human rights, enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, is not limited to political rights but also includes those to food, healthcare, secure housing and self-determination.

The latter is pertinent in the context of international relations in which the US and its allies have afforded themselves the right to wage war, impose sanctions and engage in destabilisation under the guise of “defending democracy.”

Looking back on the history of imperialist wars, is there a single one that can be said to have resulted in increased human rights? Similarly, when the US imposes sanctions on Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Syria, Iran and Cuba, do the people of these countries enjoy better lives as a result?

Or is the hidden agenda of the sanctions to break people’s confidence in their governments? If so, that would be a war crime because international law is quite clear that, for example, “food should not be used as a tool for political pressure.”

The author doesn’t hesitate to take the big Western rights organisations to task for their obscenely narrow definition of human rights. Amnesty International considers itself to be the pre-eminent defender of human rights around the world, but it didn’t feel able to oppose the criminal wars on Iraq and Libya, or even to condemn South African apartheid.

Amnesty is explicit that it “takes no position on the use of armed force or on military interventions in armed conflic, other than to demand that all parties respect international human rights and humanitarian law.”

But that’s no excuse. It simply means, as Kovalik points out, that it is refusing to take a position on the most important human-rights issue there is.

In a historical moment where global co-operation is so urgently needed to deal with the challenges we collectively face — the threat of war, pandemics, climate change and microbial resistance — the US under Trump is moving ever further away from multilateralism, as is shown by the recent decision to cut off US funding of the World Health Organisation.

At such a time, it is crucial that the people of the world demand a return to international law and the construction of a multipolar order, with the UN fulfilling its functions as the guardian of peace.

Kovalik demonstrates a wide-ranging knowledge of global politics and the book’s narrative moves from Congo to Nicaragua, Vietnam to Yugoslavia, Iraq to Bolivia. The only major blemish is the critique of modern Vietnam and the implication that, with that country’s integration into US-led global supply chains, the US “ultimately achieved its aims.”

This isn’t a fair assessment. Vietnam is an independent modern socialist country with impressive social indicators — very much not what US imperialism had in mind for it. Engaging in economic globalisation is a means of taking on board new technology, improving productivity and building a better life for the Vietnamese people.

Their outstanding response to Covid-19 amply demonstrates that they are far more than simple pawns in the US imperial chess game.

That disagreement aside, Kovalik’s book is a tremendously valuable contribution to the global struggle for peace and liberation and deserves to be widely read.

No More War: How the West Violates International Law by Using “Humanitarian” Intervention to Advance Economic and Strategic Interests is published by Hot Books, £19.99.