This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

“THE robots are coming” is the clarion call from organisations such as the European Central Bank and the World Trade Organisation, as well as in business media generally.

But it also being heeded in the university sector, chiefly in its business schools where the managerial class is incubated.

Hope and fear divide responses to the vista of robots marching over the horizon.

Warnings of mass unemployment jostle with tidings of new-job bonanzas in the tech industry.

Universal basic income is fantasised for the leisured masses, enjoying their day in the sun on the spoils of surplus value thanks to hard-working AI.

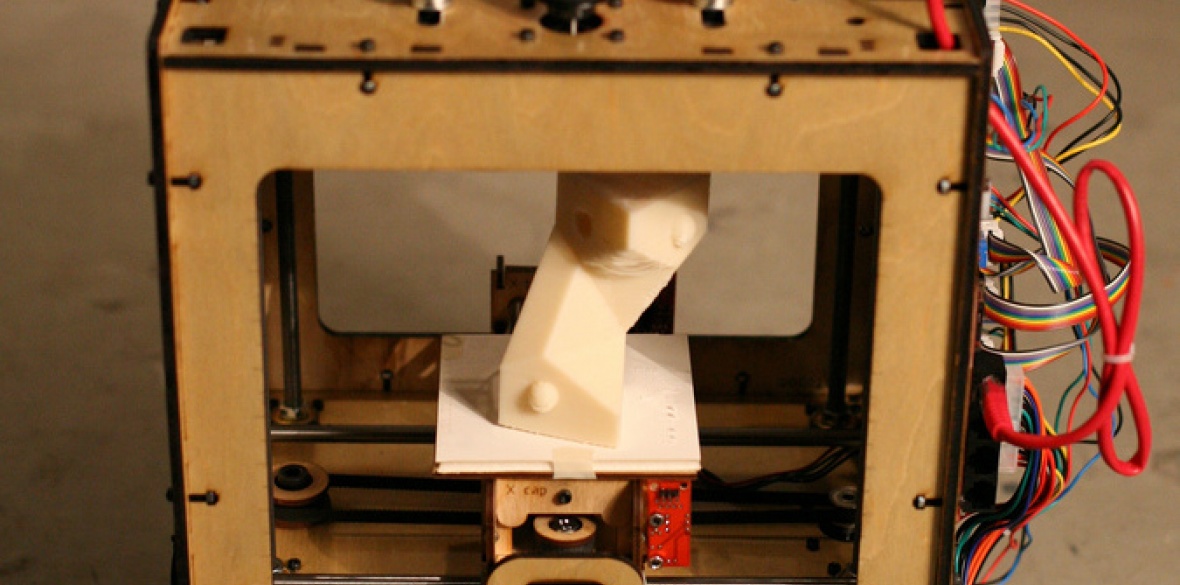

Meanwhile, personalised 3D printers will build everything from dinner to housing.

In his book Smart Machines and Service Work, US academic Jason E Smith offers a reality check to the effects of automation in an age of stagnated production and wages.

His core message concerns productivity as the dynamo of capitalism, identified by Marx in Capital, and a sustaining tenet of the industrial first world throughout the 20th century.

Smith fast-tracks through the history of negotiated wage agreements by unionised workforces, showing the link between increased labour productivity and share of profits.

In turn, this leads to increased consumption of manufactured goods, generating more jobs and so on in a sorcerer’s apprentice image of perpetual motion.

New machines increase productivity and profits grow, but workers lose jobs and consumption decreases.

For an employer to get more bang for an invested buck, increasing the work ratio —“sweating the labour” — to static or decreasing wages is a winning formula.

Globalisation is a case in point. The developing world’s workforces have widened the margins of profit for the 1 per cent while, by contrast, workers in the US have watched the American Dream fade.

Smith counters the current rhetoric of technologically driven, Shangri-La immanence with evidence of a 40-year wind-down of First World productivity to a position of deep crisis.

In Britain, the situation is worse. Smith quotes the British economist Howard Davies, who says: “UK production per hour is fully 35 per cent below the German level and 30 per cent below that of the US.”

So far, digital technology — “toys not tools” — has made little indent on the productivity index nor, Smith holds, is the tech industry investing its billions for the coming century.

Rather, workers usurped from administrative as well as industrial roles have recomposed themselves on behalf of service industries as a massively expanded, desiccated and low-paid servant class, the new “precariat.”

Smith dials up his Marx to probe several fascinating and troubling effects of this current dynamic.

The rise of the service industry manager/supervisor, business school qualification intact, has been a key means of increasing productivity during stagnation.

It may seem ironic to consider the many managers returning to their alma maters in order to gut them, but now it seems that with the rise of supervisory technologies, the machine is coming for them.

Service workers being unproductive of value per se — “they are a cost to capital … paid for out of the profits of other productive businesses,” a lag occurs.

For Smith, this explains “the productivity paradox,” where high employment figures link to poverty, not wealth, in the gig economy.

It’s as though the whale of fully automated industry were slowed down, rather than fed, by krill.

Business schools are taking note.

Published by Reaktion Books, £14.95.