This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer

Barbican, London

MICHAEL CLARK’S gleeful challenges to tradition never degenerate into farcical or raggedy amateurism because his subversive choreography is rooted in the highly disciplined and precise traditions of Scottish dancing and classical ballet.

Born in 1962 in Aberdeen, Clark was trained in Scottish dancing from the age of four. He won a scholarship to London’s Royal Ballet School at 13 and joined the Ballet Rambert contemporary dance company four years later.

By then he was already also immersed in punk culture and progressive politics after attending the Anti-Nazi League’s 1978 rally in Hackney and hearing the Clash.

Summer school in the US with the choreographer Merce Cunningham and the composer John Cage in 1982 opened Clark’s eyes to the excitement and pertinence of the avant-garde.

Two years later, aged only 22, he formed Michael Clark and Company and created his first independent work. Amazingly, he has sustained his ability to create startling, mesmerising works ever since.

Rebelling against classical ballet’s rather insular cultural references, many works are inspired by or collaborations with radical rock musicians including Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, The Fall, Lou Reed, Karole Armitage and his hero David Bowie.

He was also dazzled by the outrageous and inventive clothes, make-up and behaviour in London’s gay club culture, not least by the flamboyantly theatrical Leigh Bowery who Clark befriended.

Yet, typically, Clark also turned to Erik Satie and Igor Stravinsky.

The dynamic cross-fertilisations of ideas and aesthetics brought by collaborations with musicians, artists and fashion designers — rather than theatre costume designers — are crucial to Clark.

But he has said: “Ultimately I strongly believe the audience are the final collaborators in making the work whole. It’s something I embrace and enjoy.

“I consider it a political act in itself, that they complete the work by their perception of it.”

Delighting in flights of imagination, unexpected cultural juxtapositions and contradictions, Clark fuses references to sex, popular culture and urban street life with a curiosity about philosophy, avant-garde culture and contemporary politics.

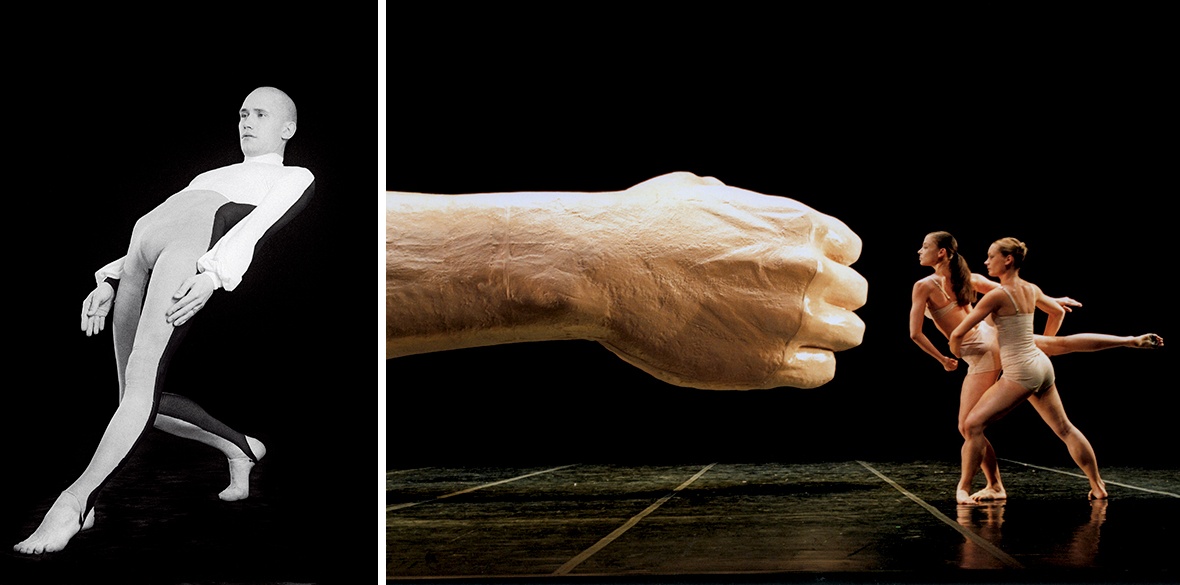

In I Am Curious Orange (1988) dancers clad in leotards and tights patterned with black-and-white geometric shapes interact with others, whose heads poke out of enormous Heinz baked beans cans.

They also appear in Celtic football outfits and are encased in giant oranges. Pithy, oblique references to William of Orange and his reputed homosexuality were direct political challenges to Margaret Thatcher’s prudish and reactionary anti-gay laws passed that year.

In the later works, including Mmm… of 2006 and To a simple rock ’n’ roll song (2016), Clark replaced roguish theatricality with exquisitely elegant sets and costumes which allow his inventive choreography to shine without distraction.

For these pared-down works, he invented unexpected steps and intricate interactions between dancers which display the beauty of the human body’s skeletal geometry and potential for superb muscular control .

The exhibition curators have created a frenetic ambience in the main ground floor gallery by suspending large screens, interspersed with small monitors featuring film of Clark’s company, plus an interview with him in which he giggles and laughs with his interviewer, which is screened twice.

Since all these screens and monitors have different sound tracks, this creates a distracting, overstimulated ambiance which crowds out the sheer beauty, elegance and rigour of Clark’s choreography and productions.

His 1980s subversiveness undoubtedly made an important contribution to British culture, including asserting the gay liberation movement’s opposition to repressive, self-righteous Thatcherism.

But by emphasising this decade the curators rather undervalue Clark’s enormous contribution to dance in the three following decades.

Those works are more subtle, complex and controlled, while continuing to expanding the dialogue between popular culture and classical dance.

And it is as much for these later works as for his mischievously pioneering ones that Clark has become one of the giants of international modern dance.

A welcome contrast to the dizzying cacophony of sound from numerous screens is provided by the quiet whirring of the 16mm film projection of Clark’s company interacting with Le Corbusier’s architecture on the roof of his Cite Radieuse in Marseilles.

One of the highlights of the exhibition, the contemplative, geometric choreography echoes and complements the daring elegance of the pared-down architecture.

Film, still photographs and dance catalogues, albeit by innovatory graphic designers, are no substitute for live performance and the exhibition made me long so very much for the end of the Covid cultural drought, when we can return to “collaborate” with Michael Clark as members of his audience.

But, in the meantime, this instructive exhibition is a well-earned tribute to one of the great choreographers of our time.

And it is good fun too.

Runs until January 3, box office: barbican.org.uk.