This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

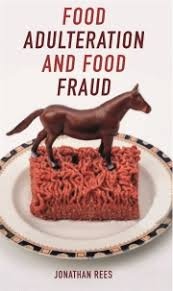

Food Adulteration and Food Fraud

by Jonathan Rees

(Reaktion Books, £9.95)

IN EARLY 2013, horse DNA was found in beef. What followed was the traditional sight of the British public in full moral panic, with sales of frozen hamburgers dropping by over 40 per cent. More recently, chlorinated chicken has become a shorthand for the debate around trade post-Brexit.

Food brings cultural values into sharp focus and in this book, a primer on the murky world of food scandals, the terms are slippery. Author Jonathan Rees defines adulteration as involving partial substitution or addition — mixing vegetable with olive oil for example — whereas fraud is a complete substitution and deception, as when horse meat is passed off for beef.

The difficulty, as Rees clearly sets out, is that many food adulterations are welcomed by consumers if the price goes down. And, as long as the ingredients are fully listed, then it's not technically illegal. But where to draw the line?

An academic historian, Rees brings a historical perspective to the subject. He points out that while global trade isn't new, supply chains have never been more complex and one way manufacturers tackle this growing distance from consumers is by creating fictional chef mascots to engender trust in processed products. Spoiler: Mr Kipling, Betty Crocker and Captain Birdseye never existed.

Rees provides plentiful factoids in an admirably compact book. There could be no industrial chocolate without soybeans being one example, and if a product is expensive, difficult to test and has a complex supply chain, it is commonly adulterated, with olive oil, spices and honey all culprits.

A particularly excellent chapter focuses on the science behind food testing. Rees explains how the "fingerprint" of a particular food can be determined with mass spectrometry to interrogate its molecular makeup, and DNA can be sequenced to see if the meat really is from the animal it says on the label.

Even organic and non-organic food, chemically identical, could one day be distinguished by nuclear magnetic resonance testing. But Rees is never blinded by the science, pointing out that the terroir (place of origin) of wine and for foods of all kinds may be entirely due to infinitesimally small differences.

While perceptible by connoisseurs, these can be almost impossible to define or detect methodically, and so regulating them is a Sisyphean task.

Rees doesn't provide conclusive answers, noting that apart from obvious toxins, most questions about food regulation must be decided with "inclination" rather than science.

He freely admits his bias towards the US and British contexts but includes informative sections about different cultures, such as Bangladesh and China.

At times, one can sense a detached amusement at public overreactions to food scandals, and he cites the historian Rachel Laudan's declaration that: "ingesting food is, and always has been, inherently dangerous."