This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IN THE only article about Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) published in his lifetime, the Symbolist poet Albert Aurier characterised him — in an otherwise complimentary text — as a crazed genius.

This commonly held perception was further dramatised and popularised by the 1956 Hollywood film Lust for Life, which had Van Gogh chopping off his own ear. In fact, the artist only sliced off a sliver during one of his intermittent bouts of mental illness, during which he did not paint, and which only plagued him in the last two years of his short life.

Tate Britain’s exhibition rectifies these skewed portrayals of Van Gogh by emphasising his intelligence, wide reading in four languages and deep knowledge of contemporary ideas, art and literature.

Son of a Dutch Protestant pastor and his wife, Van Gogh’s knowledge of historic and contemporary European art dated back to his apprenticeship at the age of 16 to an international art dealer. Stints in its branches at The Hague, Brussels and Paris ended with two years in London, where he arrived when he was 20.

There he was greatly affected by the desperate condition of the working class. Resolving to devote himself to helping the poor and oppressed, he left the art dealer and trained and practised as an urban evangelist before, aged 27, realising his true vocation as an artist. The intention was the same — he wanted above all to make a consoling art, of and for the people.

The exhibition links the content of Van Gogh’s works to his admiration for British socially conscious culture, especially the novels of Charles Dickens and George Eliot and the black-and-white woodcut illustrations of proletarian life by Frank Holl, Luke Fildes, Hubert von Herkomer, Fred Walker and others.

Displaying these prints from Van Gogh’s collection with his lesser known Hague period water-colours and drawings emphasises his work’s diversity and social awareness.These depictions of almshouse “orphan men,” ageing prostitutes and destitute women and children are a revelation.

Sensitively and accurately drawn and painted in flat areas of naturalist colour, they neither stereotype nor patronise but portray individual human beings with profound empathy.

Above all a realist,Van Gogh always worked directly from life, even in his last and best-known period in Arles and Auvers (1888-90), when he pioneered the expressive use of vivid colour, dynamic line and visible impasto brushwork to convey the essence of his response to his subjects.

His poverty, bizarre bohemian appearance and thick, Dutch-accented French made getting and paying models difficult and he frequently turned to landscapes. But these also communicate his love for living things. In Hospital at Saint Remy, the harsh mistral wind which has twisted the trees’ trunks and branches can almost be heard battering their leaves as his short, curved brush strokes echo their frenzied twirls and whirls.

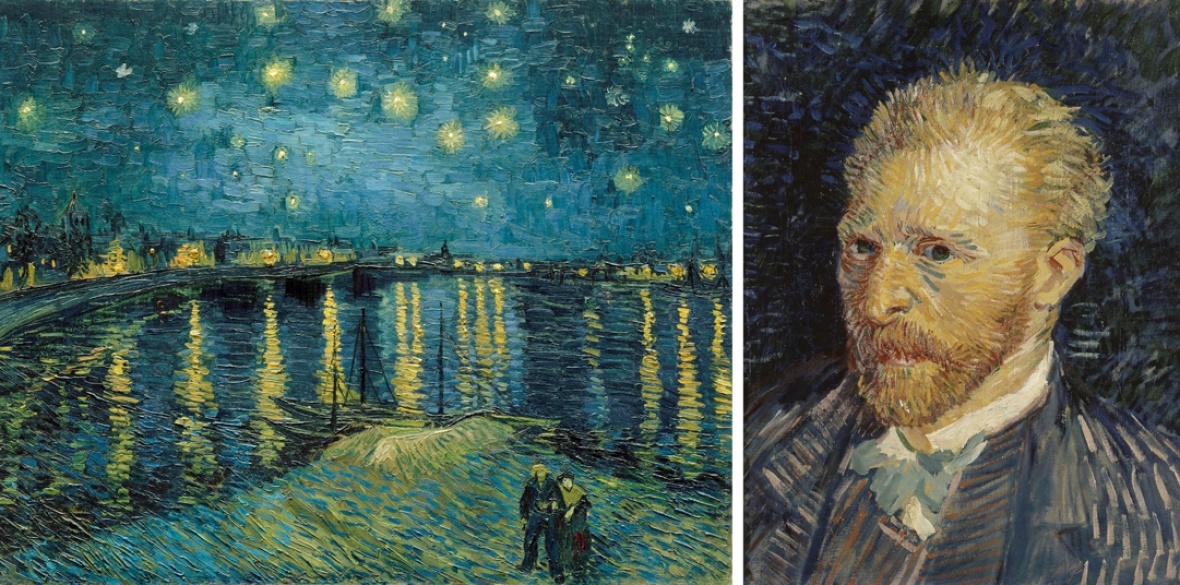

Masterpieces like Starry Night share this sense of awe in the presence of nature. The expanse of brightly starred sky rivals the golden reflections of street lights in the dark river. Painted with short, energetic dashes and spots almost entirely in blues and golds, these complementary colours mutually emphasise their impact and envelop the couple walking out on the river’s shore.

The public cluster thirstily around such true gems, drinking in their magic with pleasure and concentration, storing up memories.

It is paired with Gustave Dore’s print Evening on the Thames at Night. While this link is relatively interesting, some are frankly silly. Van Gogh’s early drawing of exhausted Borinage miners is linked to GH Boughton’s print Pilgrims Going to Church because both depict a line people in the snow. Yet they differ profoundly in style, subject and content — one indicts contemporary proletarian exploitation, the other sentimentalises 17th-century British history.

The second half of the exhibition narrates changing British responses to Van Gogh, from early outrage and bewilderment to admiration and influence on progressive artists. The works of Frank Brangwyn, Harold Gilman and Francis Bacon manage to avoid being overshadowed by the few Van Goghs scattered among them.

An interesting theme, but it’s difficult to respond to after the exhibition’s already emotionally and intellectually demanding first half, which also contains unnecessary large and gloomy Victorian paintings which Van Gogh only mentioned briefly in letters decades after seeing them.

Exhibitions which link a famous artist to a general theme often disappoint and this one would benefit from judicious pruning of tenuous comparisons. But it is thoughtful, informative and introduces a wider public to Van Gogh’s erudition, his lesser-known works and especially to the brilliant Victorian illustrators which he admired.

One of the best-loved pioneers of modernism, reproductions of Van Gogh’s late paintings have long sustained the spirits of millions of people and seeing the originals is a real treat. Go if you can.

Runs until August 11, box office: tate.org.uk