This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

ON JANUARY 25, 2022 the Thai Narcotics Control Board announced it would drop cannabis from the list of controlled drugs. This de facto decriminalises the drug, making Thailand the first country in south-east Asia to do so.

In the US an estimated 428,000 people now work in the legal cannabis industry with 38 states allowing medical marijuana and 18 states having legalised recreational use too.

In Europe Germany, Luxembourg and Malta all announced last year that they would be moving towards legalising recreational use.

There’s momentum behind the global campaign to legalise cannabis and good reasons for socialists to join the push. In Britain according to a YouGov poll 52 per cent support cannabis legalisation.

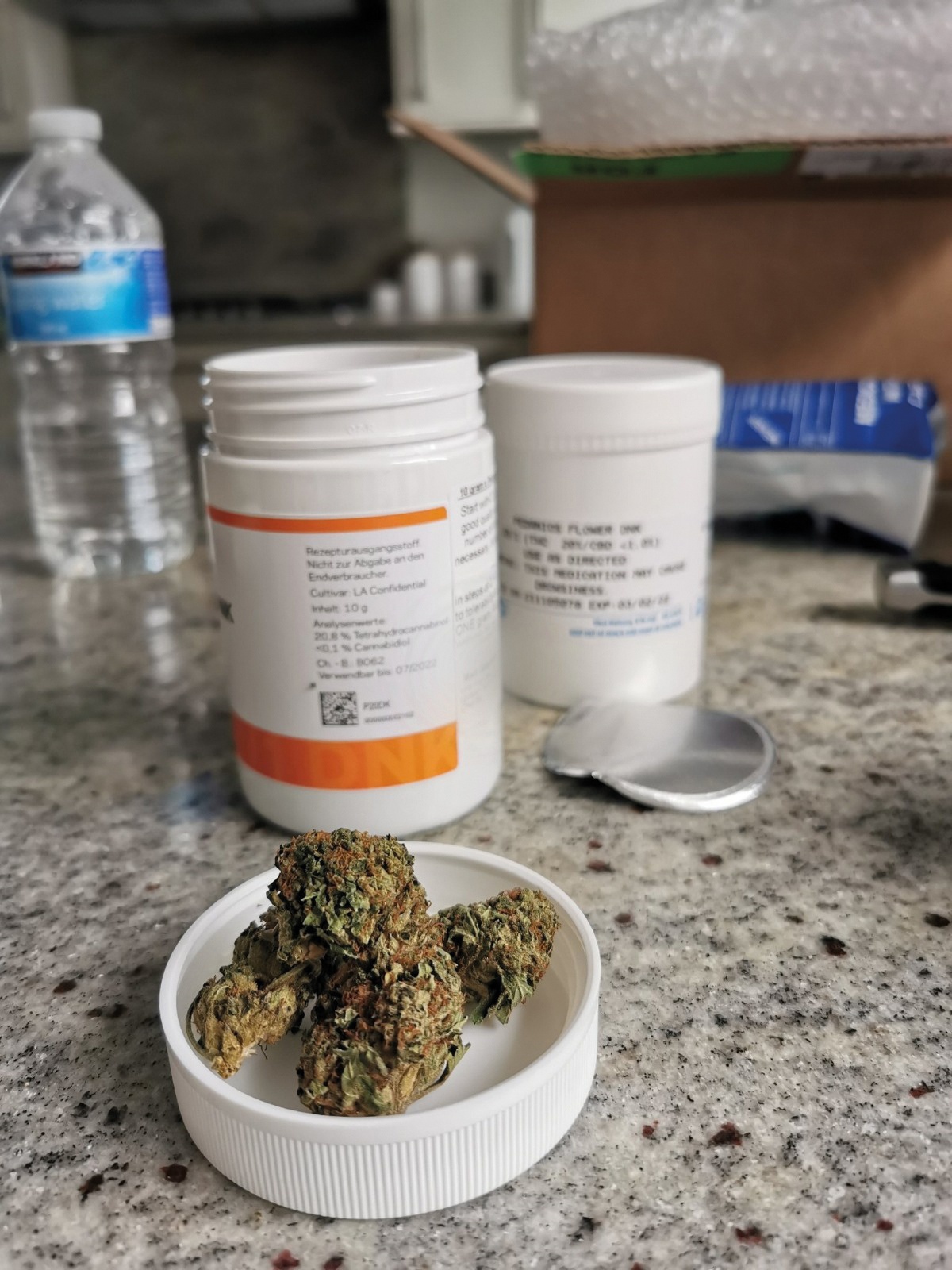

Medical cannabis has been legal in Britain since 2018 — if you can afford it. There are about 7,000 people with cannabis prescriptions in for conditions from chronic pain and epilepsy to anxiety and ADHD. Due to lack of understanding and medical guidelines forcing cannabis to be prescribed off label (potentially invalidating GPs’ insurance), almost all prescriptions come from private clinics, with only three people receiving it on the NHS.

Matt, a cannabis patient in London, told the Morning Star he pays almost double the street price for his prescription. He’d been self-medicating for six years but decided to pursue a prescription after he had two run-ins with the law last year and the “anxiety was not worth it.”

One proponent of Cannabis’s medical efficacy is Professor David Nutt the chairman of Drug Science, a non-profit he founded in 2010 to provide independent, evidence-based information on drugs.

Previously Nutt was the senior drugs adviser to Tony Blair, sacked for resisting cannabis’s reclassification to class B and for saying taking MDMA was safer than riding a horse. He recently published a book Cannabis: Seeing Through the Smoke which highlights how vital a medicine cannabis can be.

Nutt told the Morning Star about Lucy who suffers from Ehlers Danlos Syndrome, which has no treatment except cannabis. She went from being fed through a tube in ICU to a student rollerblading down Brighton seafront — thanks to cannabis. But she can’t get it on the NHS. Nutt says she was told dismissively by the NHS that it could just be a placebo effect — so she pays a private clinic.

Private medical companies pose dangers to a fair settlement in a future legal recreational market. The tight regulatory structure of medicinal cannabis means only large companies can afford to operate. This aids what drug policy think tank Transform call “corporate capture” — where large companies gain “undue influence over domestic and international decision-makers and public institutions.”

In California small legacy cannabis farmers were promised farming licenses would be limited to one acre. At the last minute, pressed by lobbyists, legislators reneged, allowing the stacking of licences creating huge farms. This caused a collapse in cannabis prices and the potential destruction of rural communities who’d relied on the income for decades.

In Britain the shutting out of black-market workers has already had consequences. Both cannabis patients interviewed described receiving mouldy medical cannabis due to poor storage.

For medical cannabis to be affordable and to ensure a more equitable transition to recreational use, it must be more widely available on the NHS.

Despite its long association with radicalism, it is not clear cut that socialists should demand recreational consumption of cannabis be legalised. In the legal markets, we see the encouragement of chronic and damaging usage — it’s not uncommon to find articles with titles like “Seven cannabis strains perfect for daytime use” on leafly.com, the world’s largest cannabis site.

Indeed, cannabis’s perception as a potentially 24-hour intoxicant has drawn interest from big alcohol and tobacco including Altria (Philip Morris and Marlboro cigarettes), Molston Coors, Anheuser-Bush InBev and Heineken.

This push was foreshadowed by Marxist philosopher Mark Fisher: “Stoner stupefication seeks only to remove tension, to become a zombified consumer… What could be better for the Komissars of Kapital than if half the population spends all their spare time smoking dope.”

A conversation needs to be had over what constitutes healthy use. The lobbying machines of legal vice can only muddy the waters.

Beyond cannabis’s medical role, Nutt makes the convincing case that state-owned cannabis is the most desirable regulatory model. He says there are “26 variables you have to take into account when you are looking at the benefits of different forms of regulation and they range from health across the board to corruption of politicians by private enterprise.”

Different types of regulatory regimes were then examined using these variables.

“We looked at prohibition as it exists today, decriminalisation, state control and a free market — and state control came out best… If you have state control you don’t have corruption of politicians, you don’t have advertising to young people. You don’t have misinformation.”

Workers’ wellbeing is the lodestar of a socialist project and thus harm reduction needs to be central in our analysis. Nutt highlights the uncomfortable truth that one in 10 people who try cannabis will become dependent on it. He asserts however that criminalisation increases the risks, as it causes the proliferation of skunk, (categorised as cannabis with 10 per cent or more THC than average, meaning lower amounts of CBD which is neuroprotective).

“The idea that [cannabis is] going to cause psychosis or the idea that it’s going to cause dependence is much more likely if you’re using strong skunk than if you’re using a balanced mixture [less THC, more CBD].

“Policy has driven the generation and sale of more toxic substances. It’s gone from hash, resin and the balanced mixtures in the ’60s and ’70s to skunk. 95 per cent of everything on the street is now skunk… And the harms are greater because it is skunk.

“That’s kind of sick isn’t it really? That the policies have done exactly the opposite of what they should have done."

In Nutt’s view, state-owned cannabis should come with the social spaces seen in the Netherlands.

“Where you don’t just have a shop, you have a cafe where you can go and smoke away from the street where people don't want the smell, where you can actually be educated by the people behind the counter who can tell you about the different sorts… What’s best for your palate, best for your needs.

“In the Netherlands the coffee shops are still under private control, but the material could be sourced at the state level and thus essentially regulated to make sure that the strengths were controlled to maybe not more than 10 per cent THC.”

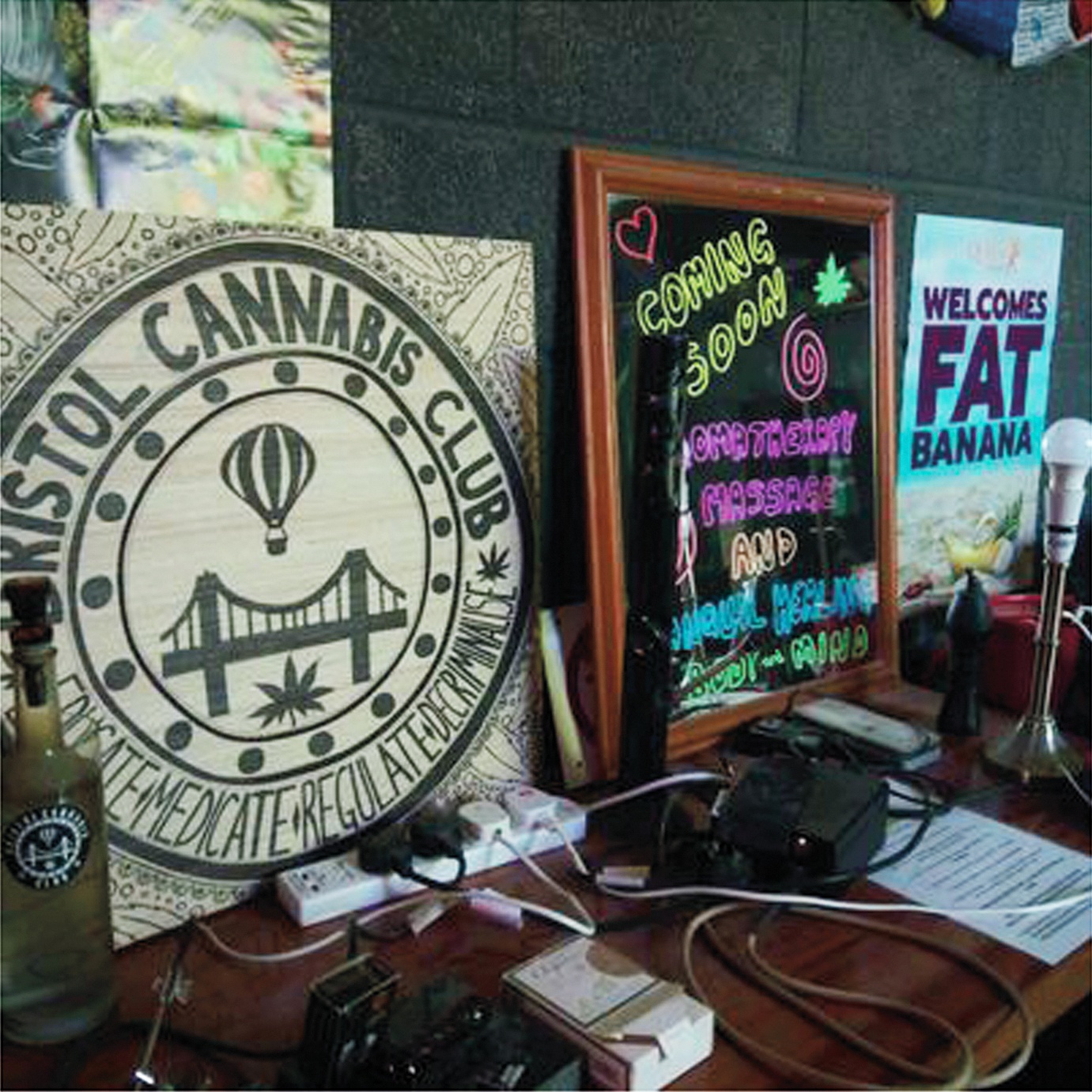

The social aspect has led to cannabis clubs being set up across Britain. Ali, a cannabis patient and volunteer for Bristol Cannabis Club (BCC) told the Morning Star, “We feel the social element is vital to connect people so they can share information and resources which leads to harm reduction and enables medical patients to better understand and treat their issues, be it with the plant or other supportive therapies.”

BCC formed in 2014 under the slogan “Regulate, educate, medicate” to ensure safe access to cannabis, especially for those with a medical need, fight for legalisation and foster harm reduction from production to use. From 2018 until it was shut by Covid, the club ran a social space, the Brunel Steam Room, described online as “a sanctuary and safe space for our members.”

Ali said: “We use the coming together of like-minded people to apply political pressure to the system while educating the public on the plant and our needs to break the stigma caused by years of propaganda… We offer safe spaces for people to talk about, vape and eat the plant.”

A tension in the case for state-run cannabis is the mistrust of the state which has persecuted cannabis users for decades.

“I think the government being in full control of any cannabis market currently is a danger we need to avoid,” argues Ali.

“Sadly, it would be like the blind leading the blind… Ideally the government would work with organisations such as ourselves, industry experts both underground from the UK and overground from legal territories overseas and private business to create a set of regulations that focus on the end user.”

Ali preferred Malta’s model which avoids the free market but allows home growing and not-for-profit growers clubs.

Socialists interested in legalisation need to counter this mistrust. The working class need power to ensure that cannabis legalisation is fair. This means building unions to establish high standards for workers in the new industry while demanding access to jobs for workers with criminal records. Community unions are required to properly engage with cannabis advocacy groups like BCC and ensure consumption spaces are genuine communal spaces that benefit patrons and the community alike.

Fundamentally, socialists should be building a society in which recreational users do not become habitual users who smoke every morning to function. For some, daily use is a medical necessity, but for others, an anti-social reaction to society’s ills — and the distorting impact of market forces will take advantage of the ambiguity between recreational and medical use if allowed. Cannabis’s benefits will be swamped and its dangers extenuated in the race for profit.

Isaac Kneebone-Hopkins is a Bristol Transformed organiser, trade unionist and Bristol Momentum organising group member — Twitter @isaac_kh.