RISING personal debt levels show that for working-class people in Britain, precariousness is the new norm.

Just as in the world of work, where casualisation means that secure jobs and predictable incomes are increasingly rare even in many “professional” occupations, Britain’s household finances are ever more fragile and people are now regularly borrowing even to fund everyday expenses like buying groceries.

Economists have been warning for over a year of the return of “stagflation” — that is, a combination of rapidly rising prices with economic recession, a double whammy that, since rising unemployment reduces the price of labour, can prompt a vicious downward spiral of impoverishment.

In British politics the term is associated with the 1970s — but after five decades of neoliberalism British households are far less resilient than they were in the 1970s.

This has a lot to do with debt. The study by financial analysts Nerdwallet refers to debts like credit card bills and personal loans: it does not even include student loans, though the average non-mortgage household debt in Britain doubles (from £5,233 to £10,145) if student loans are included, showing that the Blair government’s decision to introduce university tuition fees and the Tory-Lib Dem coalition’s decision to treble them continue to saddle generations of young people with decades of debt.

And even that pales by comparison with mortgage debt. While borrowing a mortgage to buy a home is nothing new, the transformation of the nation’s housing stock from homes built for use to assets intended to accumulate in value has massively increased household debt.

House prices now average over eight times average incomes — double the 1980 figure. It is not merely those repaying mortgages who are affected.

It is increasingly difficult for young people to buy homes in the first place and housing shortages combine with some of the weakest tenant rights in Europe to empower landlords to hike rents at will. As a proportion of earnings the average rental household is paying more than twice the average rent in the 1970s.

The debt trap makes the threat of “stagflation” even more serious than it was in the 1970s, leading economists to warn of a “stagflationary debt crisis” that New York professor Nouriel Roubini has characterised as the worst of both worlds.

The big picture is that as asset values have risen, pay has shrunk. People are not increasingly indebted because they are irresponsible spendthrifts: it is because of the cost of getting by has risen way beyond wage increases.

This is a long-term trend, but it was sharply accelerated by the “austerity” policies of post-2010 Conservative-led governments which prioritised holding pay down — and it will be accelerated again by the current Tory administration’s determination to do the same.

High household debt is a social weapon in the hands of the ruling class. Thatcher calculated that homeowners whose houses could be repossessed if they defaulted on mortgage payments would be less prone to strike action: it was a motivation for the “right to buy” policy that has devastated Britain’s social housing stock and fuelled today’s housing crisis.

The same applies to all forms of debt. It entraps people and makes them vulnerable. It can undermine the class-for-itself militancy we are seeing re-emerge across the trade union movement.

It must not be allowed to. Ultimately, people in Britain are falling into debt because they are not paid enough.

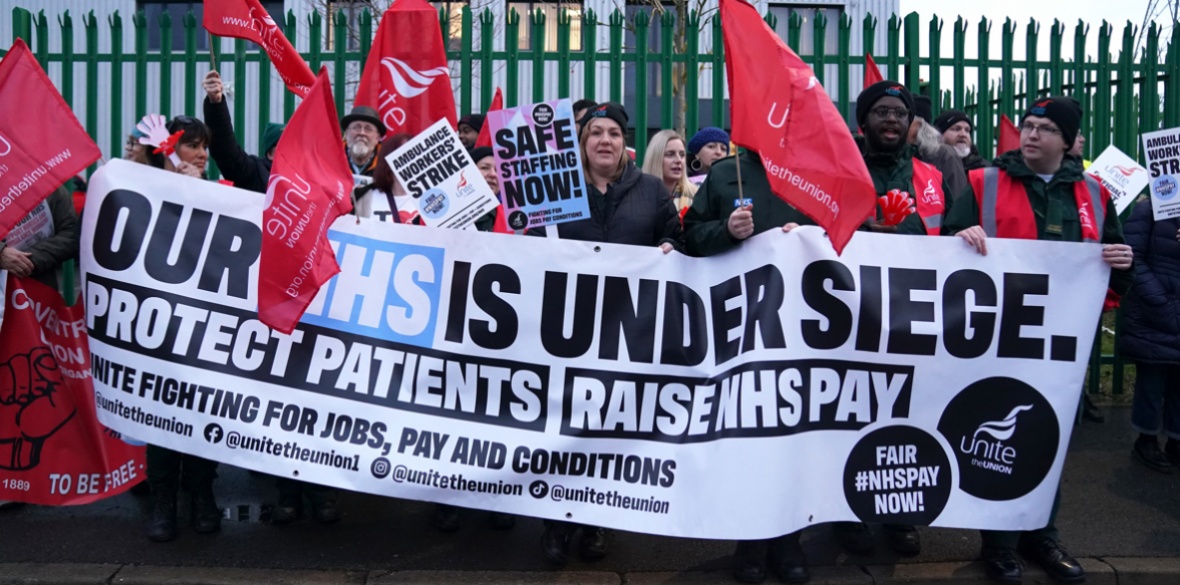

There is only one solution to that, and as millions are now discovering, there is only one way to obtain it: collective action.

Britain’s household debt levels expose an economic model that needs fixing, and the train guards, posties, health workers, cleaners and others now striking for fair pay are the ones with the tools for the job.