This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

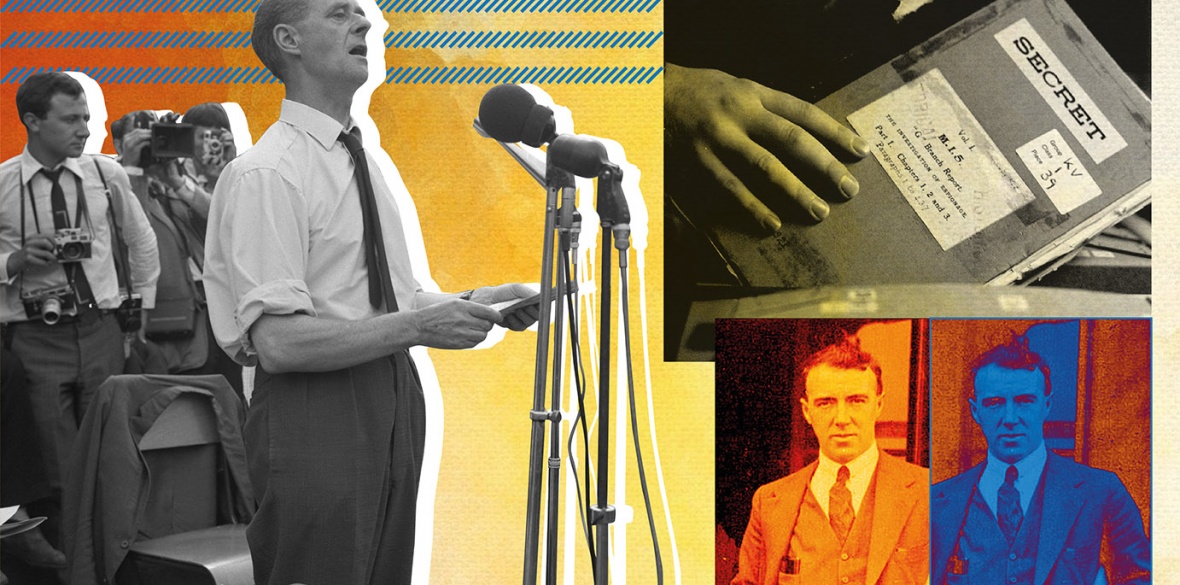

BACK in 1987 MI5 operative Peter Wright, famously revealed in Spycatcher — The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer that his MI5 special facilities team had “bugged and burgled our way across London at the state’s behest, while pompous bowler-hatted civil servants in Whitehall pretended to look the other way.”

In deep-mining formerly secret documents released to the National Archives and a wide array of published sources, this study provides conclusive evidence of how in the immediate aftermath of the second world war the British state security services amassed to themselves immense operational powers despite having no statutory authority, no statutory powers and no statutory (and little otherwise) accountability. Thus creating the conditions for the civil liberties violations and criminal behaviour disclosed by Wright.

The book is the culmination of decades of academic research by Professor Keith Ewing, a frequent contributor to the Morning Star, together with co-authors Joan Mahoney and Andrew Moretta.

It examines the powers, activities and accountability of MI5 in the period 1945 and 1964 but is by no means confined to events of that period.

It is a superbly structured work of scholarship which examines a range of topics in depth and rounds off each chapter (and the book itself) with a definitive conclusion.

The key, recurring theme of the book is the extent to which the rule of law in the post-war era was undermined by MI5’s lack of a legal mandate and accountability, the complacency of successive inquiries conducted by servile judges and the well-documented illegal activities of the security services. This happened with the complicity of Labour ministers and TUC leaders.

As far as the authors are concerned, the British constitution in the cold war period would have struggled to satisfy even the most minimalist requirements of the rule of law which MI5’s actions revealed to be a deception.

But for Morning Star readers, it is the revelatory force of this meticulously referenced book which makes it a compelling and essential read.

Long before the cold war began, the Communist Party of Great Britain had been the main quarry of the British security service.

Academics such as Jennifer Luff of Durham University have uncovered the secret ban on communists in government service from the 1920s onwards.

This included covert surveillance of Civil Service workers suspected of being communists.

In 1945 Sir Samuel Findlater Stewart presented a secret report to prime minister Clement Attlee on the future role of MI5 and justified the targeting of the Communist Party during the interwar years on the basis that “most of the persons concerned with the promotion of political aims by unconstitutional methods are members of the Communist Party,” adding that many “are exposed to, and some succumb to, pressure to engage in espionage on behalf of international communism, and at one remove, the Soviet Union.”

In 1950 the official committee on communism, established by Attlee, determined that it would be “quixotic to insist on extending to communists the protection afforded by a nice respect for the rules of that democratic system which they themselves aim to destroy.”

It was the Communist Party, its members, industrial militants, sympathisers and in some cases family members that bore the full brunt of MI5’s nefarious activities backed by a state which had a “formal policy to discriminate against communists” and to this end “it has been a stated policy that it is necessary to know the identity of communists.”

The justification for a regime of surveillance, blacklisting and vetting was Defence of the Realm yet throughout its history the Communist Party has been a lawful organisation with an open membership and political representation at municipal and parliamentary levels.

Although “the great bulk of its activity was devoted to the CP, its members and related organisations” it was not only the party but other organisations in the “communist solar system” (a phrase coined by the Labour Party in 1933, then used by the government’s Industrial Research and Information Services in 1957) who received the close attention of MI5.

These included the National Council for Civil Liberties (now Liberty), the Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers and the peace movement.

An interesting passage in the book lays bare the state-orchestrated sabotage of the 1950 Sheffield Peace Congress.

MI5 used surveillance on “an industrial scale.” Its targets and methods including mail interception, bugging, phone-tapping, infiltration and use of informers are examined in detail.

Of particular note is an extensive account of Operation Party Piece, when MI5 used “special facilities” to gain covert entry to the north-west London home of Ronald and Nancy Berger where party membership records were stored as a security measure to overcome the heavy surveillance of CPGB’s Covent Garden headquarters.

Over a two-month period in 1955, 48,000 documents were secretly removed at night from the Berger household and photographed by MI5.

Voluminous personal files exist on many Communist Party leaders, including Harry Pollitt (14 thick volumes of files until 1953 only).

The files on Pollitt’s successor as CPGB general secretary John Gollan include his extended family (niece Ruth Taylor being PF file number 815,946 in the mid-1960s).

Phil Piratin, MP for Stepney (1945 to 1950), was subjected to extensive state surveillance as well as class hatred, harassment and provocation far more severe than the vitriol experienced by Jeremy Corbyn in recent years.

Holding elected office and participation in democratic process provided no immunity to MI5 surveillance not only for communist MPs such as Piratin and Willie Gallacher MP for West Fife (1935 to 1950) but also pro-Soviet Labour MPs such as DN Pritt and Geoffrey Bing.

Police state tactics I experienced in a very minor way in 1983 when, having stood as a Communist Party election candidate for Liverpool City Council, I was questioned at home by two Special Branch officers using the pretext that my election leaflet had omitted to confirm the names of printer and publisher.

The authors skilfully juxtapose the epic and serial counter-espionage failures of the post-war period (Burgess, Philby, et al) with the blanket surveillance of the party and the far-reaching purge of communists from the Civil Service and other public agencies.

Next to no natural justice was provided to victims of the purge with TUC Congress in 1948 shamefully voting down a demand for trade union representation for civil servants in appeals processes.

Interestingly the authors find that trade union files are conspicuous by their absence in the National Archives, although some have been released, including the personal file of Electrical Trade Union leader and Communist Party member Frank Haxell, opened in 1941 and released up to 1954 only, MI5 surveillance long predating the “ballot-rigging” national controversy which occurred in 1961.

This is a historical study with a resounding modern-day relevance. The stated aim of the authors in studying the past is to better understand contemporary institutions.

Quite an understated ambition in the present era of the undercover policing inquiry, of critiques of capitalism being outlawed in schools, of deep-state-commissioned dirty tricks being exposed in the Assange trial, of the US imposing a broad immigration ban on communists and not least of Sir Keir Starmer, a true heir to his party’s cold war warriors of yore, declaring that national security is Labour’s top priority under his leadership and steadfastly refusing to oppose the Covert Human Intelligence Sources Bill which licenses criminality by MI5 and police informants.