This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

ON DECEMBER 3 The Sunday Times carried a full spread on the subject of US intentions with regard to North Korea in the light of its latest successful intercontinental ballistic missile test.

This missile flew high and far, dropping finally into the Sea of Japan.

The calculation has been made that with a more horizontal trajectory it could reach all of the US mainland. North Korea may not yet have the technology to fit such a missile with a nuclear weapon but the US may, more than ever, be likely when militarily ready to initiate war if some incident — perhaps accidentally arising — has not already triggered it.

To Washington, the desirability of talks aimed at reducing tensions, whether conducted directly or through intermediaries, is not self-evident. Indeed, the only alternative cited to war and invasion of the North (not excluding a preemptive nuclear strike) is simply ongoing “containment,” in view of “the received wisdom of the US foreign policy establishment that the South Korean death toll in any war was unacceptable.”

“Containment,” of course, offers no promise of future peace.

Tim Beal’s 2011 book Crisis in Korea was written against an earlier background of war tensions and his comment on the realities of a ground war against the North no doubt holds good today:

“Obviously the US would expect the (South) to provide most of the troops, fill most of the body bags and administer the conquered territory.”

But since Beal wrote this, the raised possibility that nuclear bombs could be used — and perhaps by both sides — makes the prospect of another Korean war still more terrifying.

If the assumption is made that North Korea’s leader — “nuclear-armed madman” Kim Jong Un — wants war and therefore the destruction of his homeland (which in the 1950-53 conflict was devastated by bombing and napalm beyond imagination) — one could understand the wish of the US to protect itself and its dependent ally South Korea.

But this assumption, spread far and wide by mainstream media, is falsely predicated.

Kim Jong Un is often presented as if he is his country’s only inhabitant but North Korea is a country of 25 million people — occupying 55 per cent of the whole Korean peninsula — and more than two million people live in the capital Pyongyang.

Though not a paradise, its high-rise housing blocks, well-looked-after parks and tree-lined boulevards and its cleanness have not given visitors an impression of a city on the verge of starvation or internal rebellion.

In his informative, if not always balanced, 2015 book on the North (sub-titled State of Paranoia), Paul French noted that housing — which is allocated by the government — is subject to severe overcrowding, that the electricity supply often breaks down and that there are serious food and other shortages.

French, however, does not examine the impact on the country of the long-term sanctions and threat of renewed war. Beal, on the other hand, draws from an article published by the North’s state news agency in 2010, which listed categories of economic damage suffered and even attempted to quantify it in dollar terms.

It is impossible for most of us to sympathise with some aspects of the style of government applied in North Korea, including its “political re-education camps,” the extreme cult of personality for its leader — tied to hereditary succession and severe restrictions on the right of individuals to express views considered anathema by the regime. But the people of North Korea have the right not to be the victims of external attack.

Since the armistice of 1953 the North has been committed to a form of socialism, to political independence and to self-sufficiency — an objective summarised in the Korean word “juche.”

In this context, its centrally planned economy — whatever its drawbacks — has achieved a solid and substantial industrial base.

The country is also “the most militarised country on the face of the Earth,” in the words of US professor Bruce Cumings, who remarked too that militarisation was not so visible to a traveller.

The country is what it is in part because its governments have responded defensively to the attempts by its enemies to thwart its fierce insistence upon independence.

“ It is impossible for most of us to sympathise with some aspects of

the style of government applied in North Korea but its people have the right not to be the victim of external attack ”

For more than six decades, it is an inescapable fact that successive US administrations have neither sought a final peace treaty nor established diplomatic relations with the North. The “hermit kingdom” has received harsh encouragement to remain one.

Beal’s book described the response to an overture, by the North, to the US in 2002 for talks (then led by Kim Jong Un’s father Kim Jong Il). White House deputy national adviser Stephen Hadley did not need to consult anyone. Direct talks, he said, would “reward bad behaviour” — so there were no talks.

North Korea’s “bad behaviour,” looked under the microscope, has always included as a core element the bare fact of its continuing existence — a “behaviour” which has been endlessly punished by US economic sanctions and an intimidating military stance.

The major exception to the gloves-off, sanctions on, US approach was the October 1994 “Agreed Framework,” signed on behalf of both countries. Earlier that year North Korea’s founding leader Kim Il Sung had died — as discussions were progressing — and his son Kim Jong Il had succeeded him.

In the Agreed Framework — a title which accommodated US squeamishness about the use of the term “treaty” — North Korea surrendered its option to develop nuclear weapons in exchange for benefits it considered more essential.

Both countries promised — in the agreement — to move towards normalising political and economic relations by first establishing a liaison office in each capital then moving towards an exchange of ambassadors, to reduce barriers to trade and investment and to work towards a nuclear-free Korean peninsula. Central was the issue of nuclear development.

In return for the freezing of the North’s graphic reactors and a return to full inspections under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, two “proliferation resistant,” light-water reactors would be supplied to the North with loans and credits to be made available to facilitate their purchase. Moreover, in the short term, heavy fuel oil would be supplied by the US.

North Korea was not a reluctant party to this agreement. It had pushed for it after being alarmed by the resumption of aggressive military exercises featuring 50,000 US and 70,000 South Korean troops.

After threatening in 1993 to withdraw from the NPT in May 1994, the North shut down its reactor at Yongbyon, ruling out charges of game-playing.

Though the new Clinton administration seems at that moment to have been as much inclined to a new war with the North as to co-existence, at this point former US president Jimmy Carter stepped in with a personal mediation attempt, breaking the impasse and facilitating the Agreed Framework.

The US follow-through faded, influenced by calculations that the North’s economy would fail and that the regime would fall. No advance towards diplomatic relations. No light-water reactors. The US had lost interest and in late 2002 the George Bush administration withdrew altogether from the Framework.

In 2009 Carter stated in a press interview that in his view the agreement could easily be reinstated: “It could be worked out, in my opinion, in half a day.”

The Sunday Times piece, predictably, did not concern itself with the history of US enmity towards North Korea, with the long-term desire of its leaders for peace and the country’s independence, or even with a diplomatic way forward.

A State Department official was quoted as saying, however, that the bombing and invasion of the North, and its occupation by the South’s military, with a view to a reunified Korea, was “the kind of cavalier wishful thinking that led us into disaster in Iraq.”

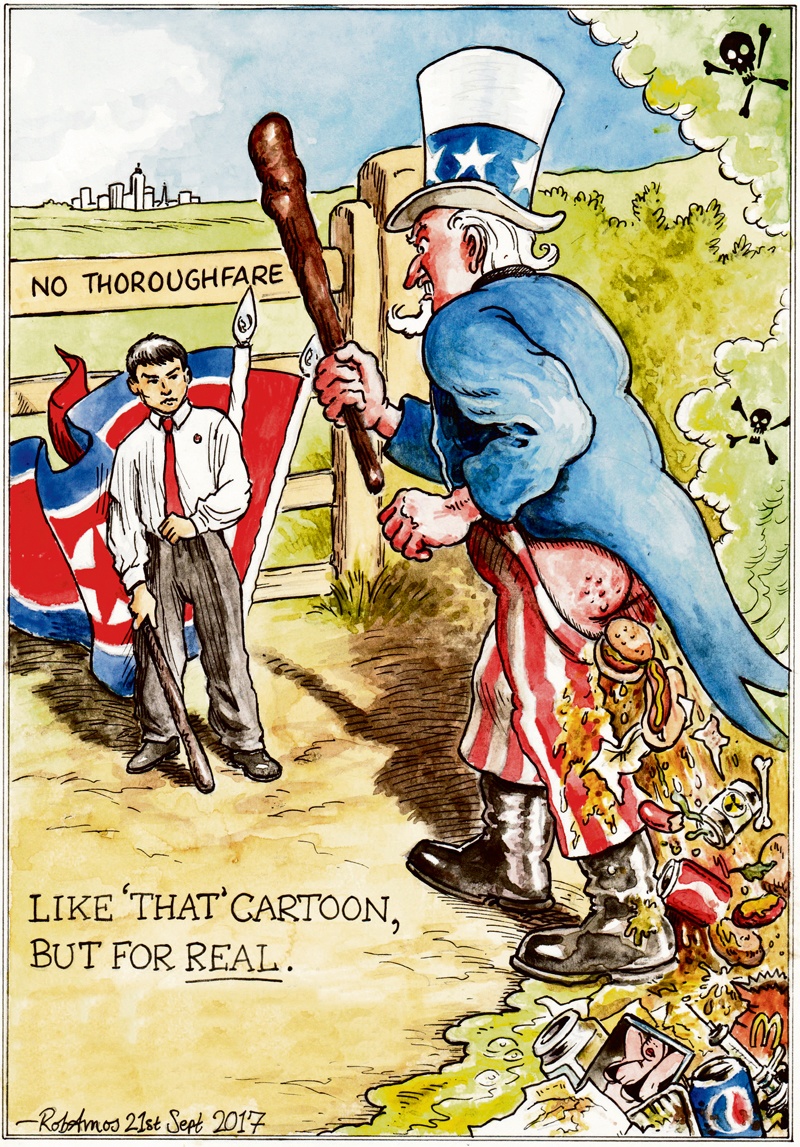

The impression grows from the US refusal to contemplate standing down from its own belligerent position in exchange for the same from North Korea, that the real “madman” is in residence in both the White House and the Pentagon.

War, which could begin as nuclear, or could become nuclear, is unthinkable.

But the US may be thinking it. And planning it.