This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

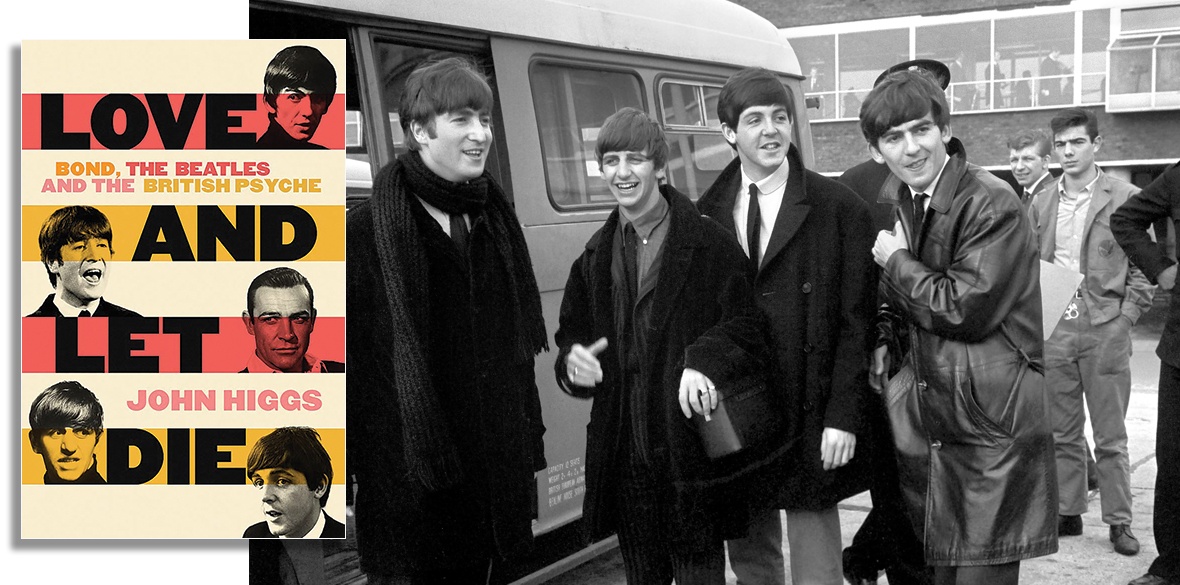

Love and Let Die: Bond, the Beatles and the British Psyche

by John Higgs

Weidenfeld & Nicolson £22

LOVE and Let Die starts with the odd coincidence that the first Bond film, Dr No, and the first Beatles single, Love Me Do, were released on the same day, October 5 1962. After this the book becomes a dialogue between the world of Bond and the world of the Beatles.

Higgs characterises this as the difference between Thanatos and Eros in the Freudian dialectic, with Bond representing the death instinct, and the Beatles representing love.

It is also about class. Bond is the Establishment. He has the Establishment’s sense of superiority. Like his creator, Ian Fleming, he went to all the right schools, had all the right connections, and spent his life defending upper-class privilege. He’s a snob.

The Beatles, on the other hand, are working class. They kicked down the door that had blocked working-class people from their full potential. They were bold, funny, sharp-witted and intelligent, as well as being almost supernaturally talented.

After them came other working-class bands, like the Kinks, the Animals, and the Who, and working-class actors and writers and artists in almost every art form. This was the time when Britain became, almost, a meritocracy. Anything was possible, it seemed, if you were brave and hard working enough.

Not that it has lasted. These days the working class are back in their box. The airwaves are dominated by well-off kids with family connections who can afford to buy the equipment needed to take up a career in music.

Higgs tells a good story, which he heard from the writer Hanif Kureishi who went to an all boys’ school on the borders of Kent. In 1968 his music teacher insisted that the Beatles did not write their own music. It had to have come from someone from a more cultured background, like Brian Epstein, or George Martin, he said.

This reveals the attitude of the Establishment at the time, and is a strange parallel to England’s other world-renowned genius, William Shakespeare. Like the Beatles, Shakespeare’s creative originality has often been disputed, based upon the idea that a person from such a humble background could not possibly have written such sublime works.

There are two views of England here. There’s the geographical location, from which the Beatles emerge, complete with regional accents and a sense of community: and the ideology of empire, which is transnational, and represents concentrated wealth and power.

Like Bond, the empire is globetrotting, ruthless, psychopathic. Like Bond it has “a licence to kill.” It trades in arms and wars and will destroy anything that gets in its way.

It is also stupid. As Higgs says: “Some of these people are so uninspired that all they can think to do, when they possess more money than they could ever use, is to try and make more. Typically, it does not occur to them to be embarrassed by this.”

This is Higgs’s seventh book, but the first in which he has stepped outside his countercultural preoccupations and written something that might appeal to the mainstream.

It is not a history, although it contains historical elements, many of which will be familiar to older readers. Higgs cuts through some of the myths, and gives us a new perspective on this age-old dialogue between images of class and masculinity.