This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

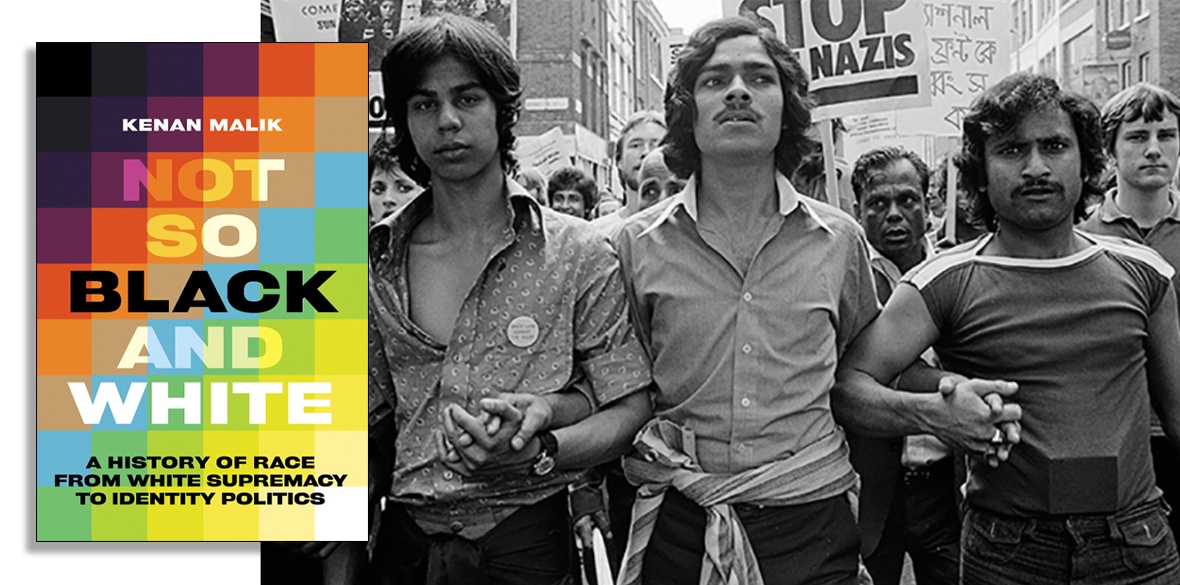

Not so Black and White

by Kenan Malik, Hurst, £20

NOT so Black and White starts from Kenan Malik’s own experiences of racist violence, growing up in the 1970s, when he describes “Paki-bashing” as having been a national sport.

It was these experiences that drew him into political campaigns against street violence, police brutality and racist deportations, issues that are all too relevant today, whatever the differences in the ways in which racism is discussed, in the contemporary context.

While it was racism that drew him into politics, however, it was politics that made him see that “there was more to social justice than challenging the injustices done to me,” widening his understanding of race and racism through his engagement with the writings of Karl Marx, as well as through the writings of black authors such as WEB Du Bois, CLR James and Franz Fanon.

Part one of the book, “The Barbarism of Race,” tells the story of the rise of the concept of race and of white supremacy, and part two, “The Struggle to Transcend Race,” of the development of movements against racism and their decay into contemporary identity politics.

The approach is both historical and conceptual, exploring ideas as these have been developed in specific contexts over time.

Enlightenment ideas are central to his analysis, especially Enlightenment ideas about universalism and equality.

Critics have dismissed Enlightenment thinking as Eurocentric, pointing to its inherent contradictions, promoting the Rights of Man while supporting the institution of slavery.

While acknowledging these contradictions, Malik also points to the more radical strands within Enlightenment thinking. And he explores the development of the concepts of race and white supremacy as ways of attempting to manage the Enlightenment’s inherent contradictions, trying to find ways to justify treating black people unequally and with profound injustice.

There is also a chapter on the development of anti-semitism in modern times, along with a chapter on the ways in which the brutalities of colonialism foreshadowed the horrors of the Holocaust.

German colonists committed genocide in south-west Africa, for instance, just as the British developed concentration camps during the Boer war.

The second part of the book focuses on Enlightenment ideas and their influence on radical struggles for freedom and equality.

He starts with the Haitian Revolution, which began in 1791 and culminated with Haitian independence in 1804.

This was the third of the great Enlightenment revolutions, following the American war of independence in 1776 and the French Revolution of 1789.

Although this third revolution is less well known in the West, it was extremely significant in Malik’s view, not only as the first successful major slave revolt and the first successful challenge by a black nation to the might of Europe, but also because it reframed the meaning of the “Rights of Man,” making it far more difficult to accommodate Enlightenment ideals with the existence of racism and colonialism.

Not that this prevented Europeans from continuing to talk of Man, yet continuing to commit murder in all the corners of the globe, as Fanon observed, reflecting on European imperialism in practice.

However, in Malik’s view, Enlightenment and universalist ideals have had contributions to make to radical struggles and the ways we think about race and identity.

The book goes on to explore the contributions of black Marxist thinkers such as WEB Du Bois and CLR James, who saw black internationalism universally, as an aspect of working-class politics and global class struggles.

Malik then moves on to focus on black and working-class struggles in the US. There were attempts to organise across racial lines within the IWW (Industrial Workers of the World, or “Wobblies”) movement, for example, but overall the labour movement failed to challenge racial divisions effectively despite the US Communist Party’s commitments to organising across the racial divide in the inter-war period.

Reflecting on struggles in more contemporary times, Malik concludes by emphasising the importance of class politics. Class divisions matter on both sides of the racial divide.

The shift from class politics to identity politics has contributed to fragmentation on the left, in his view, delinking economic and political struggles.

The book concludes by emphasising the importance of restitching together the economic and the political, resurrecting the connections between racism and other forms of inequalities, breaking the bounds of identity politics, and reconstructing radical universalism not as an idea but as a social movement.

In summary, Not so Black and White provides a rich account of the history of race, from white supremacy to identity politics, and there is much to recommend in this book as a history of ideas with ongoing relevance for contemporary struggles for equalities and social justice.

Despite its overall length and its scholarly references, this is also clearly written and readily accessible.

Highly recommended for readers with an interest in engaging with these debates on race, class and identity politics.