This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

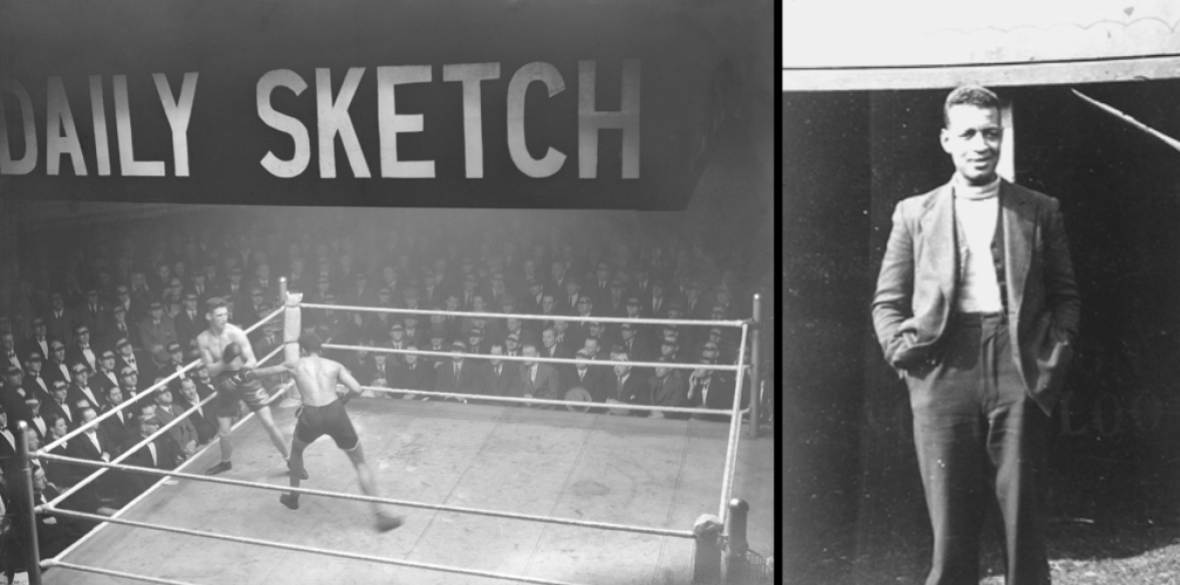

LEN JOHNSON was born on October 22 1902 in Clayton, Manchester, to an Irish mother and a father from Sierra Leone.

In a boxing career spanning a decade between 1923 and 1933, at middleweight he fought an astounding 134 bouts, winning 95, losing 12 and drawing 7.

Yet despite this remarkable record, he was prevented from fighting for a British title by the British Boxing Board of Control under the board’s then racist rule 24, which mandated that only fighters born from white British parents could do so.

This particular rule was added to the board’s constitution in 1911 with government backing, and it remained extant until 1948. In the year it was removed, Dick Turpin became Britain’s first black champion when he defeated Vince Hawkins in front of 40,000 fans at Villa Park to take the middleweight title previously coveted by Johnson.

Dick Turpin’s brother Randolph, who also fought at middleweight, would subsequently go on to become world champion in 1951, defeating the legendary Sugar Ray Robinson in London.

The point is that without the prolonged struggle waged by Johnson and his supporters, among them Paul Robeson, against the colour bar in British boxing, the feats of Dick and Randolph Turpin would not have been possible. It is why his story matters.

Johnson’s early education in the sport took place as a teenager in the boxing booths that were a fixture of travelling fairs across Britain at the time. It was there he developed the defensive skills necessary to survive against men considerably older and stronger, as he took on all-comers.

In 1925, having struggled to find opponents due to his skin colour and ability, he defeated reigning British middleweight champion Roland Todd twice in just seven months. That same year, Johnson also faced and defeated Ted “Kid” Lewis, whom Mike Tyson once claimed was the best fighter to ever come out of Britain.

You would think, given the magnitude of these achievements, that Johnson would’ve been heralded as a great champion that the country could get behind. However, due to the board’s colour bar, the aforementioned fights were fought as non-title bouts.

Understandably frustrated at his inability to fight for a title and have his achievements in the ring recognised in Britain, in 1926 Johnson decamped for Australia, where he faced and defeated Harry Collins to win the Empire (now Commonwealth) middleweight title.

The triumphant return to his home shores this achievement should have secured him did not follow, however, informed as he was by the board that his title was not recognised in Britain.

In the book about Johnson’s life — Never Counted Out — by Michael Herbert, Johnson is quoted lamenting his fate: “The prejudice against colour has prevented me from getting a championship fight. I feel now that there is no use whatever going on with the business.”

Though prevented from rising to his rightful place in the sport of boxing and being nationally renowned, Johnson was embraced as a local hero in Manchester.

As Herbert writes: “They’d all stay up when he had his big fights at Belle Vue. They’d wait until his taxi brought him home and there’d be a big cheer.”

Meeting Paul Robeson in 1932 in Manchester proved a seminal moment. Robeson urged Johnson to mount a legal challenge against the British Boxing Board of Control. He also inspired him politically, to the extent that Johnson, after retiring from boxing, joined the Communist Party of Great Britain.

In this capacity, along with fellow Manchester communists Wilf Charles and Syd Booth — the latter a veteran of the Spanish Civil War — he helped establish the New International Society (NIS) in Moss Side.

The aim of the NIS was the championing of the universal application of human rights regardless of skin-colour, gender, religion or ethnic background. It became a prominent civil rights organisation in postwar Britain, campaigning against and exposing racist employers and discriminatory housing policies, among other racial injustices that were prevalent at the time.

In 1949, Johnson again met Robeson in Manchester while the latter was in Britain touring the country to raise awareness of the plight of the Trenton Six, a group of six African-American black men controversially accused, convicted and sentenced to death over the murder of an elderly white shopkeeper in New Jersey in 1948.

Johnson was also active in the cause of Pan-Africanism and was chosen to be one of the local delegates to the Fifth Pan-African Congress, held in Manchester at Chrolton-upon-Medlock Town Hall between October 15-20 1945.

It brought together 87 delegates representing 50 organisations from across the world. Among the most prominent delegates in attendance were Kwame Nkrumah and Jomo Kenyatta, both of whom would go on to lead successful anti-colonial struggles in Africa.

In 1953, Johnson himself led a movement that successfully ended the discriminatory policy followed by pubs across Manchester at the time whereby they refused to serve black and brown people.

Johnson arrived at the Old Abbey Taphouse near the centre of Manchester one night. After the landlady refused to serve him, as he knew she would, along with his friend and comrade Wilf Charles, he mobilised a crowd of 200 to descend on the place in protest.

In response, the landlady backed down and agreed to serve Johnson and other black patrons, prompting a chain reaction across the city.

The Old Abbey Taphouse is today a community pub where the lives of Johnson and Charles are celebrated. Meanwhile, a campaign to raise money to erect a monument in Johnson’s memory has drawn the support of various local dignitaries, including Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham.

Co-founder of Black Lives Matter Manchester, Deej Malik-Johnson, is in no doubt that Johnson “was always there supporting people. Like so many, he was doing what was right but not getting the rewards for it. For him to finally get that recognition would be huge.”

One of Britain’s finest fighters inside the ring and one its greatest fighters against racial injustice outside it, Len Johnson died aged 71 in 1974.