This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

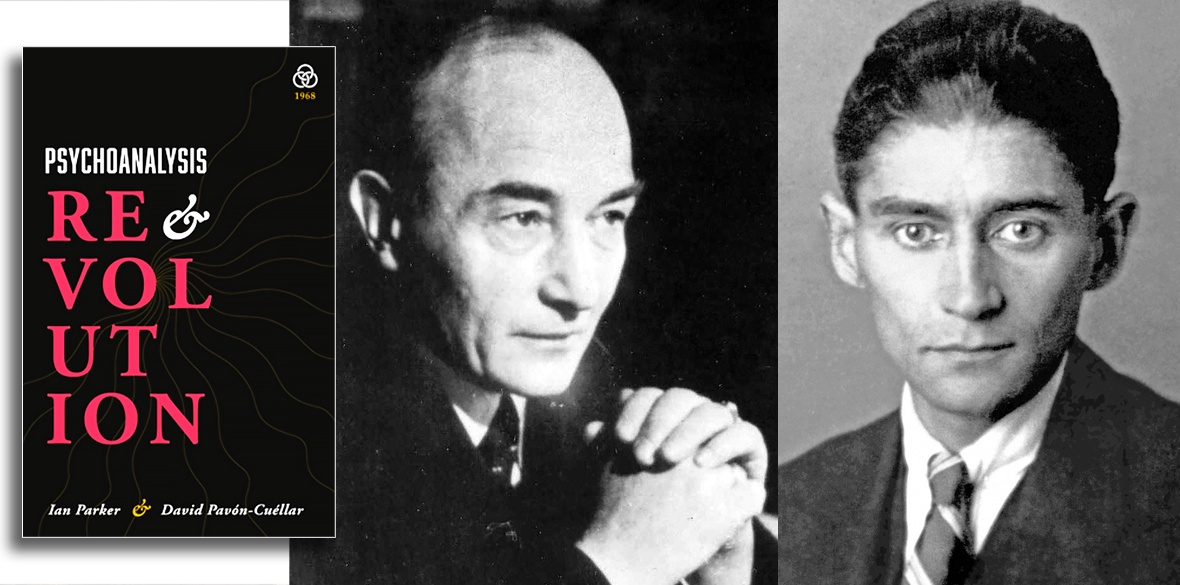

Psychoanalysis and Revolution

by Ian Parker & David Pavon-Cuellar

1968 Press £9.99

POPULAR notions of the purpose and practice of psychoanalysis were established in the golden age of Hollywood. In Spellbound (1945), Dr Constance Petersen, played by Ingrid Bergman, uses psychoanalytic techniques to resolve inner turmoil and enable a dysfunctional individual to come to terms with social reality.

Ian Parker and David Pavon-Cuellar reject the notion of psychoanalysis as a means of inward reflection. Instead, they reclaim it as a process of collective struggle, setting it in opposition to the cycle of accumulation and profit in which society is trapped.

Psychoanalysis and Revolution begins with a historical critique of professional psychoanalysis. A therapeutic tool with the potential to provide “a clinical and political critique of misery” has been used to foster a sense of isolation and resignation. No psychological theory or technique is free from ideology, they argue, but psychoanalysis can become a revolutionary practice in both clinic and culture.

Key psychoanalytic concepts are considered in relation to collective liberation. The unconscious is commonly seen as obscure and situated in a person’s “asocial depths,” but the authors dismiss this as an ideologically loaded “commonsense” model of thought and behaviour. Instead, they define the unconscious in Marxist terms, as “an ensemble of social relations” beyond our control and awareness. Some aspects, they argue, are embedded in language and symbols – features of the social landscape that influence us, but which we tend not to analyse.

The book goes on to consider “repetition” as the replication of oppressive structures; “drive” as a force that can negate or affirm life and liberty; and “transference” as a phenomenon that can privatise or socialise feelings and experiences.

The arguments are interesting and persuasive, but not always accessible. Inquisitive general readers could find the book a bit of a slog. Years ago, my initial engagement with Freud and Jung was augmented by their case studies and mythic archetypes, but Parker and Pavon-Cuellar’s presentation of psychoanalysis as a “theory and practice of liberation” is conducted in purely abstract terms.

It is clear the practice of psychoanalysis can serve revolutionary change and support the development of “good citizens,” but the book does not demonstrate the discipline’s unique importance in this respect. Could the quest for “subjective transformation” be equally well-served by reading the philosophical novels of Robert Musil and Franz Kafka?

Another issue is the dismissal of psychology as a reactionary discipline. The existence of racist, sexist and homophobic psychologists, contemptuous of working people, does not suggest their attitudes and values are inculcated by the discipline.

These reservations aside, Psychoanalysis and Revolution offers a compelling argument that new behaviours will require new ways of thinking about ourselves.