This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

ON Saturday 22 July last year, a police officer chased 20-year-old Rashan Charles into a shop in Hackney. Charles was allegedly acting suspiciously.

Grabbing Charles from behind, the officer threw him face down and jumped on him, holding him down. The dangers of face-down restraint are well known to police: it can cause positional asphyxia, and is supposed to be avoided.

By the time he was handcuffed, Charles was limp and unresponsive. He died there, on the tiled floor of a convenience store on Hackney’s Kingsland Road.

The press tends to move on quickly from such deaths, in part because, sadly, they are not a rarity. But many bereaved families in this country will never be entirely able to move on.

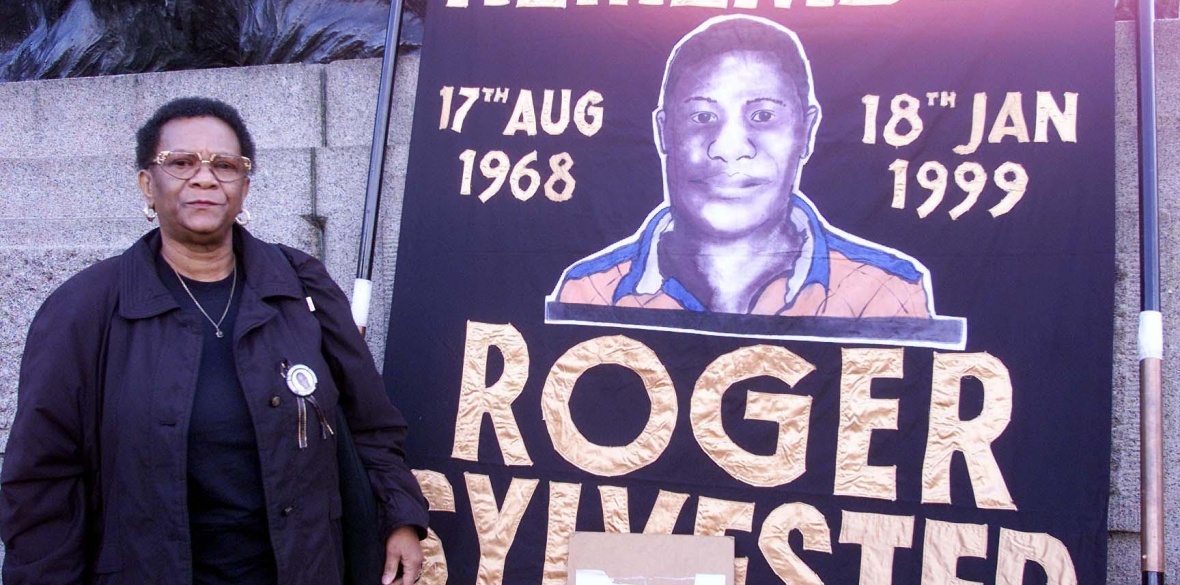

The distressing footage of Charles took me back 20 years, to the death of 30-year-old Islington Council worker Roger Sylvester and the privilege of being involved in his family’s battle for the truth.

Roger was an admin worker at Lambo Mental Health Centre in Islington, and a Unison workplace steward. I worked in the union office; he quite often popped in.

He was a quiet man with a gentle presence, but obvious warmth. We used to talk about music, football (more him than me — he was an Arsenal fan, I was hugely indifferent to the sport, despite working in Gooner territory) and the future — the inevitable late 1990s conversations about the forthcoming millennium and the so-called Y2K coding bug that, according to some media commentary, was going to bring civilisation to its knees.

Roger, very knowledgeable about computing, didn’t buy that, and was looking forward to 2000 with optimism.

An unprovoked racist attack when he was a teenager had left him with depression, but he was turning a corner — a “changed man,” his mother Sheila said. Sister Tracey agreed: he was himself again. Caring, thoughtful and wanting to help others. His mental health worker called him a “model patient,” making excellent progress.

Roger was pivotal to his family; an efficient administrator at home as well as work, he would call to remind people of upcoming birthdays, and was always the peacemaker in disagreements: he would, Tracey remembers, always urge the taking of the high road, and tell others: “You should be bigger than that!”

His family was extended, close and supportive — his cousin Beverley Renwick was like a sister and best friend in one, and he doted on her little girl, Micha. Beverley told me she called Roger her “counsellor” — always there for advice.

Roger never did get the opportunity to see in the millennium. He’d spent Christmas and new year of 1998-9 with family, and seemed well and happy at a family christening on January 10.

The next day, January 11, he had the day off, and helped his cousin Ann at her mobile phone shop in Tottenham.

Afterwards, walking back to his flat in Summerhill Road, he’d told a friend he had an odd feeling he was being followed.

It later transpired police had run a stop and search operation in the area that day. At 9.30pm, a neighbour called 999 to report a “naked black man” banging on a door over the road.

Neighbours later said Roger was knocking on his own door, for reasons that remain unclear. The police would later suggest Roger was suffering “excited delirium” caused by cannabis; but witnesses say he was clearly distressed at being naked, and desperately trying to cover himself and get back inside. His brother Bernard suspects something happened in his flat.

Roger would never get the chance to explain. Two police officers initially attended that evening; one, Sergeant Andrew Newman, said he assessed Roger needed to go to hospital, and called for back-up.

An astonishing six further officers arrived in a van. Roger was then restrained, according to some testimony, face down and naked in the street (“The coldest night of the year,” his father Rupert would later tell me, deep anguish in his voice, “and they couldn’t cover him?”)

The officers denied using prohibited face-down restraint or causing any injuries to Roger — though post-mortem examinations showed deep bruising around his neck.

Roger was taken in handcuffs to the emergency psychiatric unit at St Ann’s Hospital. There, six officers continued to restrain him, despite the handcuffs.

Nurse Ben Bersabel would tell the inquest Roger was held face down, and was calling for a doctor.

Dr Deborah Lawton confirmed she saw Roger held “belly down,” and later found him “limp and motionless,” with “spit and carpet fluff around his mouth.”

Roger stopped breathing. He was resuscitated but never regained consciousness; life support was switched off on January 19.

The family’s long fight for justice had begun. At an early meeting of their campaign, poignantly held in Roger’s old bedroom at his parents’ house, I saw the reality of the burden our system places on families of those who die in custody.

While manifestly still in shock, the Sylvesters had to immediately begin fighting, at the highest level, institutions with vastly more resources, which often appeared to close ranks against them.

Although his parents were experienced and respected community campaigners who had opposed racism for decades, that’s little help when reeling from the loss of a child.

Moreover, campaigning forced them to dwell on agonising details most of us would rather close our minds to in early bereavement — they had to become experts on Roger’s injuries, to contemplate and articulate exactly what he suffered.

While Roger still lay in a coma, the briefing against him began; a police statement claimed he was “aggressive and vociferous” on January 11. This was later retracted as completely false.

The then coroner, Freddie Patel, alleged Roger was a “crack cocaine user.” He in fact used nothing stronger than an occasional joint; Patel was disciplined, and eventually struck off in 2012, the General Medical Council finding him both incompetent and dishonest. But the misinformation fed into a familiar, racist narrative of a “crazy black man” on drugs and on the rampage.

After a four-year battle by the family, assisted by the organisation Inquest, a jury reached a verdict of unlawful killing in 2003.

They found Roger died from brain damage and cardiac arrest and that “more force was used than was reasonably necessary causing a significant contribution to the adverse consequences of restraint.”

They concluded he had been held in the restraint position too long, and denied medical attention.

Only then did the Metropolitan Police suspend seven of the officers involved: Phillip John Steedman, David Alan Clohosy, Ian Alexander Smith, Sean Kiernan, Andrew Philip Newman, Simon Paul Creevy and John Anderson.

The family were overwhelmed with relief: but the suspended officers fought the verdict; it was overturned the next year and the men reinstated.

Roger’s family took a collective decision then to withdraw from legal campaigning.

In July 2014, police admitted undercover officers from the Special Demonstration Squad had spied on 18 grieving groups of families and friends seeking justice for deaths in custody, and that “the majority” were black.

The Sylvester family are participating in the inquiry, though it’s not suggested their campaign was involved.

However, the admission raises questions about use of resources, and whether police were focusing on facilitating, or obstructing, justice.

The Sylvester family say today: “Throughout our ordeal, we were told that investigators would learn lessons that would reduce deaths in custody. We now believe that the lesson they were learning was how to build on a process that denies justice for death in custody victims and their grieving families. Roger and other victims, and families like us, are the ones paying the price in this learning exercise.”

Every new Roger Sylvester or Rashan Charles seems to confirm this.

Deborah Coles of Inquest, who worked with the family 20 years ago, says now: “Roger’s was a pivotal case in exposing the brutality, negligence and racism institutionalised within the police force, the absence of accountability at all levels … and the failure of the criminal justice system to deal with police responsible for violence and misconduct.”

She praises the family’s achievements: “[Their] relentless campaigning … was so effective in raising parliamentary and public awareness on these issues; they remain an inspiration to other families. Their struggles informed some of the policy changes and reforms to the investigation and inquest process. However, there’s no room for complacency — concerns about black deaths in police custody remain.”

On the 20th anniversary of Roger’s death, his sister Tracey reflected: “They say time heals but after 20 years, some of us are still grieving. Losing Rog has left a void in all our lives. We miss his warm personality and his smile.”

Roger Sylvester would have been 50 years old now, perhaps with children of his own.

His parents, Rupert and Sheila, point to the one fact no amount of official justification can ever change: “If the police did not lay their hands on Roger that night, he would be alive today.”