This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

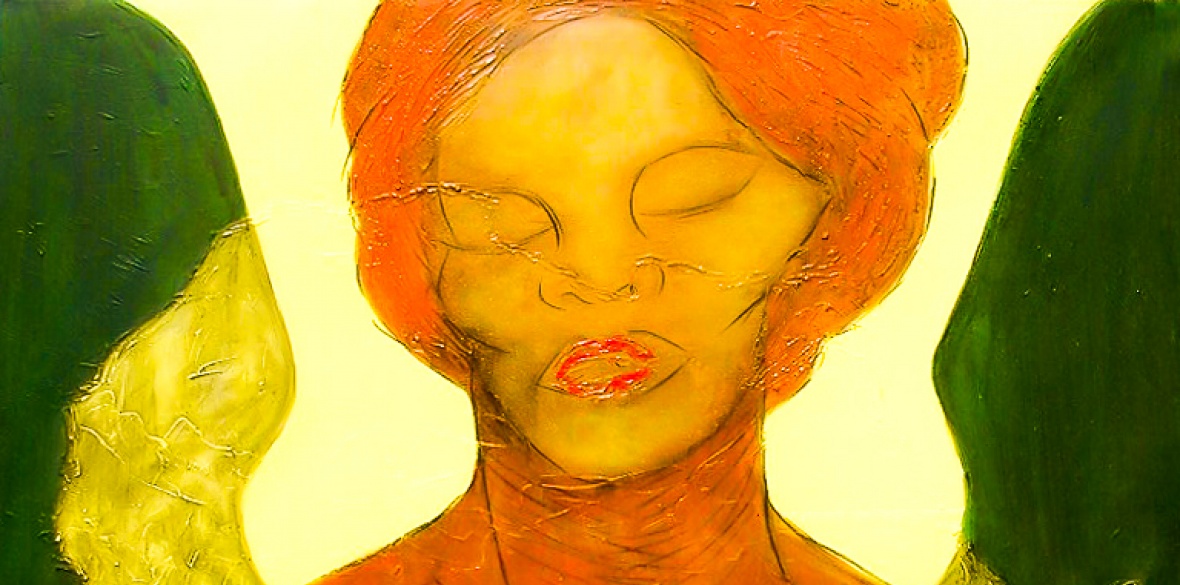

LESTER McCOLLIN SPRINGER is a Rasta artist from Las Tunas in the east of Cuba, whose vibrant images combine expressiveness with abstraction.

Many of them feature women, not as sweet playthings but as powerful bearers of their African roots and colonial history in the Caribbean.

Aged 40, he's a serious artist, not conforming to the laid-back, ganja-smoking image of Rastafarians.

His work is known and respected in Cuba, yet, in Britain where he's currently based, his talent has struggled to be recognised. In this interview, he talks about his artistic dedication in the face of opposition and misunderstanding and the importance of Rastafarianism in his life.

When did you start painting?

From age four, I started to draw in books, magazines and exercise books. Anywhere I could find a space to draw, on any blank space, I would leave my mark.

This got me in trouble with my mother and the teachers. The pressure for me to give up art started from an early age. I suffered the refusal and disrespect of my father, the only great detractor that I have known until today since he, like many at that time, considered the arts as a weakness in all its aspects and as a non-respectable profession.

I owe my further development and maturity to my mother, to Raul Alvarino who became my teacher when I was seven and to a cousin [who was an] artist, Jorge Eversley.

No-one has inspired in me more respect than the teachers in Las Tunas, where I studied art until the age of 21, when I graduated as a professional artist. Their aesthetics differ from mine, but the consistency and discipline in their work are elements that I appreciate.

How do you choose your subjects?

Most of my themes are socially related, while some are from a more intimate perspective. In 1998, I chose to give a black aesthetic to my work because I understood that what I best knew was myself as a black person, my family and the people closest to me, not all of whom were black.

I decided to pay homage to my ancestors from sub-Saharan Africa. What makes my art distinctive is images of Rastafarian men and women.

My beginnings as a professional were influenced by the naive current. Then, with experimentation, I became more expressionist in terms of form and colour. I created a symbology which, after almost 20 years of hard work, has made my art unique.

Collections like So Much Things to Say, Jardin de los Mil Suspiros (Garden of a Thousand Sighs), Trapped Voices and Ashe are a demonstration of this. I paint houses inside bodies as symbols of our diversity as Caribbean people and as human beings, keys symbolise the challenges that we face in passing through life, female bodies and Rastamen are core elements in my work and reflect mother nature, the Antilles, our ancestors.

They are my extension, my vision in each moment of my life. They motivate me to communicate with the world around me.

What does Rastafarian culture mean for you?

Rastafarian culture is the basis on which I build my life. I keep learning about it, it is a process of evolution, where respect for African roots prevails, respect for life in general, the relationship between human beings and nature.

I use only Rastafarian aesthetics, symbology, colours and figures to convey a message of rebellion, of acceptance of my roots. Rasta philosophy belongs to human beings in any part of the world. In my artwork, love, loss of love, history are very specific to my Caribbean heritage.

What do you think about the misogynistic attitudes common among many Rasta men?

I understand that there are some misogynist attitudes within it, but from what I have experienced I do not believe that it is what characterises the movement.

We Rastamen have a solid, important, necessary and eternal bond with women. We are grateful to life for them. Women are not simply our other half. We and they are as one. There are no differences from a human point of view.

Being misogynist would be completely illogical. It would go against our philosophy, concepts, ways of living and I dare say the origins of humankind. If you know my work, you would see that being misogynist has no place. By representing the female figure in many contexts, forms and interpretations I reinforce my position as a Rastaman and a human being who rejects all forms of discrimination.

I show my respect to our companeras as an artist and a Rastaman. Regardless of the many different opinions, experiences, social status and whatever defines gender differences, I intend to express my tribute to women.

Rastamen respect their female energy because it is important to recognise they are part of us as we are part of them, we are joined in pure harmony with the universe. Women are half of humanity and are respected by Rastafarianism in contrast to the image created by some rap lyrics.My way of seeing and identifying with the world is rooted in that culture.

Did you work as an artist in Cuba before you left?

I worked as a teacher in art school and in a gallery of small-scale sculptures, the only one of its kind in Cuba. Meanwhile, I kept producing my art pieces, absorbing from the experience and expertise of my colleagues who are excellent professionals.

It proved quite challenging as my strong personality and strict discipline were not always well received. This unfulfilling experience put me off teaching art, although I am grateful for what I learnt.

After approximately 20 years of professional work as an artist, I have shown work in 70 exhibitions, in different countries. In Cuba, despite the challenges, I always had many opportunities to exhibit, including key events like the Festival del Fuego in Santiago de Cuba.

In Jamaica, Poland, England and Belgium I did not know the art scene, so I exhibited in small venues such as cafes, community centres, libraries, theatres and town-hall spaces. More recently, I have worked particularly in Brighton and Hove.

What is it like to be a black non-British artist in Britain?

I have not encountered either support or discrimination for being a black foreign artist in this country.

My art is irreverent. The colours are bold, powerful, pure. In my work, I carry all the warmth and colours of the Caribbean, all the passion of my soul. And, as I am not orthodox or apologetic, I hit against the cultural, social and aesthetic barriers of British culture.

In Cuba, talent is valued greatly. You can be black, white, red or yellow — what counts is talent. As a black artist, I built my name and developed as an artist in Cuba. I am not only black. I endorse universal themes through a black aesthetic and this has been respected.

What future plans do you have?

My most coveted project is Wingless Angel, which is promoting the art of my Cuban colleagues here in Britain through a series of exhibitions. It will generate funds to be reinvested in the project. Some of the proceeds will go towards institutions that work with children with disabilities or terminal illnesses. I value their work immensely.

I need financial help, as I aim to produce maybe over 100 pieces in big formats, paintings, sculptures, prints and to cover the transport of Cuban colleagues’ work, logistics and marketing. I want to promote exhibitions in other countries, especially the EU, to expose our Cuban art to a wide and diverse public, start conversations and exchange ideas.

And I would like artists of other nationalities to join the project, so it can be enriched with cultural and spiritual diversity.

Details of The Wingless Angel project are available at springercuba.co.uk. This interview first appeared in Sounds and Colours, a website and print publication focused on South American music and culture, soundsandcolours.com