This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

TWO Jewish families pile onto carts and flee world war one as it rages across what is now southern Poland. A couple of decades later, their children are a step ahead of the nazis, escaping Vienna to London. Those left behind perish.

Relatives in Greece slip into the mountains when the nazis invade the island where they live and fight with the resistance. After world war two, surviving members of the Hirschhorn family emigrate to the US, where young Norbert Hirschhorn becomes a doctor, works in some of the poorest countries, develops a rehydration system that saves 50 million lives and is made an “American Health Hero” by President Clinton.

Finally he retires and becomes a respected poet.

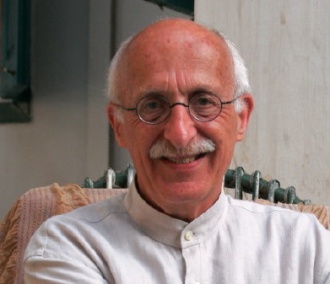

It's the stuff of Hollywood, but Norbert Hirschhorn, who recently turned 80, is in no hurry for a posthumous movie. “I hope I've got another 10 years left. On the other hand,” he winks, tapping his forehead, “there's probably a little senior cognitive decline in there, so maybe I need to wrap my life up.”

In fact, he is, if anything, embarking on a new mission to bring his family history of refugees back to life. His latest book of poems, Stone. Bread. Salt. is partly a moving meditation on his wide-ranging life and partly a celebration of his footloose Yiddish heritage. But it's another book he calls the “most important I've been involved in.”

It's a privately published collection of family letters from the last couple of centuries. He stumbled across them six years ago, was instantly struck, and had them printed privately for his family. In Yiddish and German, they reveal the intimacy of quotidian life for Jewish tradespeople, their terror at being uprooted and going on the run and the struggle of starting all over again.

Included are letters from his mother, who never recovered after being forced to leave her parents in Vienna. They couldn't get permits and were exterminated. There are also letters from his uncle, a socialist who joined the Greek anti-nazi resistance before escaping the murderous right-wing regime Britain installed after the war. Copies of the books are held in museums.

“I cry when I read them,” Hirschhorn says. “I really cry and I want my grandchildren, nieces, nephews and cousins to feel their power too. “At this stage of my life, my purpose is to connect the younger generation with history and show what they can bring to life by understanding what their forbears lived through.”

Later, he quit a prestigious teaching post at a US medical school where he had invented the discipline of rehydrating sick children and went to Lebanon , where he met Syrian doctor Fouad M Fouad, his closest friend.

He helped translate some of Fouad's poems for inclusion in his latest book. Now Hirschhorn has one foot in north west London and another in the Lebanese capital Beirut. “When you spend time in another place, you respect the way people are, you look for commonalities and respect the differences,” he says.

“That's one of the great gifts working in public health has given me.”

The importance of history is understanding the present, he stresses, particularly when the ghosts of the 1920s and 1930s are looming large.

“It's bullshit that the UK, the US, France, Italy and others complain about refugees. During world war one, Vienna took in hundreds of thousands of people and in the last few years Lebanon has taken in 1.5 million. We should admire Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey.

“War and disaster force people to start all over again and only some manage. Just think of Grenfell Tower. People can absorb change, find sustenance from family and friends, but we have to give them a chance. Besides, refugees contribute wherever they are.

“Still, the fascists in America, Britain, Italy, Austria, Hungary want to stir up hatred. The fascists never went away and we've got to resist. The blinkered intolerance they espouse is “the exact opposite of what Judaism teaches us,” he adds.

“Nobody learns from history unless you keep reminding them. You can't give up doing it.” Which he won't, he chuckles.

“At my age, I'm only just starting to mature — 80, I'm finally becoming a mensch.”

Stone. Bread. Salt: Poems by Norbert Hirschhorn is published by Holland Park Press, £8.

The Disappeared

What makes us human is soil.

Even landfill of bones, shredded jeans;

mass graves paved over for parking.

What makes us human are portraits

— graduation, weddings —

mounted in house shrines and on fliers, Have You Seen?

Names inscribed around memorial pools

or incised on granite. Names waiting,

waiting for that slide of DNA, or any piece of flesh —

for the haunted to be put to rest.

What makes us human is soil.

To stare into a hole in the ground,

fill with the deceased, throw earth down,

place a stone. Bread. Salt.

For Fouad Mohammed Fouad