This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

FOR the last 10 years in London and other Western capitals, Nike has promoted something called “Air Max Day” which is a “cultural celebration” of one of their famous models of shoe and takes place every year on March 27 — the original release date of the shoe back in 1987.

Nike enlists the help of its agents and influencers, paying them to encourage their networks to — quite literally — celebrate the birthday of a Nike shoe like it has a soul. And, of course, the only way to celebrate this mass-produced shoe (almost certainly made in slave labour conditions) on the day is by — you guessed it — buying more of the same mass-produced shoe. Thoroughly festive.

Not this year. The 10th annual Air Max Day dropped like a deflated balloon in London and hopefully marks the end of this gross display of Western complicity and privilege.

That is a result of an uprising by creatives in solidarity with Palestine, unwilling to any longer act as agents for the megabrands helping fund Israel’s genocide.

Nike still clearly felt it appropriate to ask its London agents and influencers to celebrate a mass-produced shoe owned by the warmongers of Wall Street while — along with our own government — they help fund the hell raining on the Palestinian people trapped inside a walled-off death zone, being systematically slaughtered and starved.

The handful of agents and creatives in London who still decided to take Nike’s shilling and promote Air Max Day this year were swiftly forced to remove their posts due to the now increased resistance and awareness among the creative community, and the negative press that was unfolding while these posts remained live.

Brands, street culture, complicity and resistance

The early 2000s saw the emergence of a new “creative industry” in London — one where global brands sought to buy into regional subcultures by enlisting the help of the capital’s cutting-edge creatives to sell their products and in turn secure cultural/consumer allegiance to their brands.

In 2005 I was an 18-year-old stepping into the world of work and trying to make a living as a freelance artist through my skill set which could only really be credited to having spent my entire teenage years painting graffiti pieces rather than any formal training reinforced by certificates.

Street art was booming in Britain at the time due to the groundbreaking approach of certain artists whom the liberal elite was enamoured with. It favoured the more palatable accessible street art as opposed to traditional letterform graffiti which is more coded and connected to youth criminality — therefore often less inviting or easy to package up and sell.

I’d recently started making street art following years dedicated to traditional graffiti culture. It was new, interesting and connected to the world of illustration, art and design — a world I was very keen to work in.

I was well positioned to access the streams of revenues provided by this fast-growing industry, being commissioned by companies such as Virgin and Topshop. I’d created murals for both inside their Oxford Street premises by the age of 19.

I was celebrated by my peers for these achievements and was certainly proud of them myself at the time. I was a shining example of how the neoliberal West can host your “entrepreneurialism” and “fulfil your creative dreams.” However, by the end of the 2000s, this neoliberal dream had started to look a bit ugly from where I was standing.

London was heavily sanitised ahead of the 2012 Olympics meaning the once gritty and mysterious subcultures of graffiti and even the musical genre of Grime had started being erased, demonised, oppressed through legal action or commercially diluted.

With the 2008 recession hitting people’s pockets, it was no longer easy to make a living through selling people artwork. Furthermore, austerity removed almost all government arts funding and policies to support creatives were ditched, which meant that by the time the Olympics came around it seemed the only real money available for creatives in London came from the private sector — the global brands.

Instagram and the era of ‘the influencers’ arrives

At this point I became very disillusioned with my career choice — I had not got into graffiti, art and subcultures in general to find myself milling around in Shoreditch and Soho competing with other “creatives” for the opportunity to sell our skills and subcultures to global brands.

There could not have been less cultural romance attached to this period in London’s history, so I walked away from it. However, the industry grew rapidly in London following the 2012 Olympics and the arrival of Instagram that same year.

The cultural hype around certain Western clothing brands accelerated worldwide to levels never previously seen thanks to this new app’s ability to enable people to build their own creative content profiles, gain huge worldwide followings and then sell their following to the brands via clothing collaborations or paid ads with them wearing the gear.

This was the age of the influencer where the lines between an artist, model, content creator and brand ambassador had become blurred. For the global brands to achieve these cultural inroads they almost always need to go through trusted agents.

These people are hanging out at all the parties and events keeping up with the next hype and making sure they form solid links with whoever that is so they can later sell their talent and social reach to the brands for a profit.

This industry has expanded to huge proportions since 2012, becoming an absolute free-for-all of marketing London subcultures to Wall St warmongers for big personal profits.

After Gaza: creatives wake up

It has only been in the last six months during the genocide in Gaza that we have begun to see a serious pushback against these complicit brands and their position within London’s creative industry and its attached subcultures.

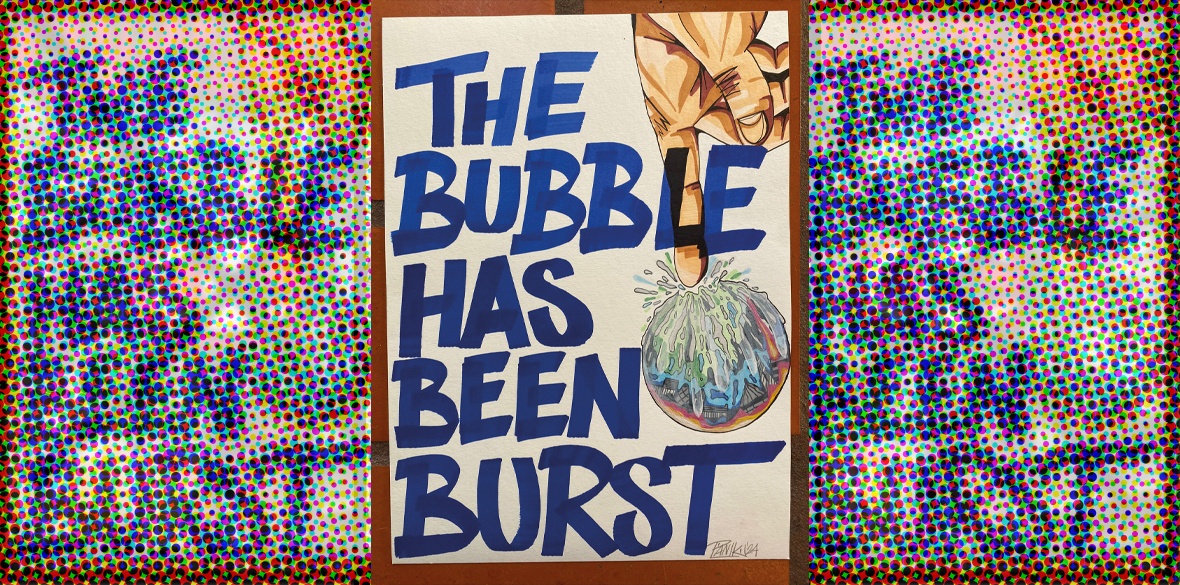

As the BDS movement strengthens and the genocide in Gaza continues to expose the complicity of those tied to the US military-industrial complex, it feels for many of my generation who were raised in places like London that the neoliberal bubble that we’ve been living in all our lives has finally burst once and for all.

We’ve been faced with the unavoidable, glaring truth, that our continued support of these brands, even as a consumer, plays a direct role in funding the ongoing genocide.

Even now not everyone wants to get out, and even those that do want to can’t always manage it overnight; it’s a process of untangling not just your finances but also your mentality from certain brands.

Realising that for all these years you’ve been operating as an obedient consumer, helping fund US war crimes with your brand allegiance is not an easy thing to come to terms with — and I write this as someone who’s always had a solid understanding of the dangers attached to capitalism.

Many tangled up in this industry, while coming to this realisation, seem to be experiencing the discomfort of cognitive dissonance as they wrestle with the morality of their position. They use excuses and spin in order to justify their own actions — and just want business to resume as normal.

That is a risky position to take when “normal business” is a genocide that’s already cost the lives of around 15,000 children alone in the last six months.

Thankfully the artists and creatives of London, Manchester, Bristol, Glasgow and right across the country are organising to push back from within against these complicit brands.

If the Western leaders will not impose economic sanctions on Israel then we’ll have to do it ourselves.

And we should broaden the net to include the global brands owned by the US military complex, that way directly divesting from Israel’s source of funding and damaging the profits of those in Wall St who seek to keep the Middle East in a perpetual state of war for their own personal gain.

The creative community in London has the ability to make sure the message is firmly delivered to those sitting at the top of these brands that the doors are no longer open for business here.

That effort is now well underway. This year, on March 27 2024 the message was successfully sent to Nike HQ that the day was in fact not their 10th annual Happy Air Max Day but instead day 173 of a Western-sponsored genocide in Gaza in which their company is complicit — and don’t forget it.

London Creatives Corporate Watchdog, a direct action, BDS movement to challenge the presence of unethical corporations within London’s creative industry can be found on Instagram @lccw_alliance.