This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Exhibition review Lindsey Mendick: SH*TFACED; Grayson Perry: Smash Hits

Jupiter Artland; National Galleries of Scotland: Royal Academy

IT’S not every art exhibition that begins with a heath warning. But with Lindsey Mendick’s new “confessional show,” the clue is in the name. A rather stylish plaque tells us that the venue “condones a sensible approach to the use of alcohol,” warning that the “scenes of binge drinking” depicted in SH*TFACED could be “challenging.”

This is one of several shows at this year’s Edinburgh Art Festival which grapple with shame, repression and defiance.

Mendick’s exhibition spans across three spaces within Jupiter Artland, a private sculpture park and contemporary art gallery on the estate of a Jacobean country house in Kirknewton, West Lothian. Its first rooms take the form of a nightclub and adjoining toilets. Distorted chequered walls and a soundtrack of club sounds disorientate us before we are confronted with an expansive and intricate scale model of the club we believe we are already within.

At its centre are the circles of hell from Dante’s Inferno, now requisitioned as a dance floor. All around, model figures take part in the all the fun of the fair — hen parties, dance moves and binge drinking — their bright, plasticky look giving them the allure and repulsion of sex toys. Mendick herself is pictured first in hen night jollity, before being mirrored across the circles of hell as a sexualised Cerebrus, and finally materialising as a dog pissing on the cloakroom counter.

“Duality is in all of us, we’re neither fully good nor bad,” says Mendick. Her reference point is The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, which she says “resonated deeply with my daily inner struggles navigating the realities I face day to day.”

The wild ride continues through the pleasingly dank club bathrooms, where the sociality of the ladies’ materialises in a sculpted representation of Mendick’s own head, emerging from a toilet bowl. Here, the life-size ceramics and contrasting brightness allow us to appreciate the intricacy of her craft: the surface of the face crawls with the heightened consciousness that can overtake us in moments of intoxicated realisation.

This message is brought home in Shame Spiral, a intimate film of Mendick’s journeys through intoxication and “hangxiety,” before being thrown into sharp relief by the exhibition’s conclusion, I Tried So Hard To Be Good, a display of stunning white ceramics mimicking an opulent dinner party in the Jacobean ballroom.

The class distinction between the two forms of drinking at play was on Mendick’s mind, but she refuses to cast judgement.

But refreshingly, Grayson Perry, whose first British retrospective takes centre stage at Edinburgh’s Royal Academy, does not.

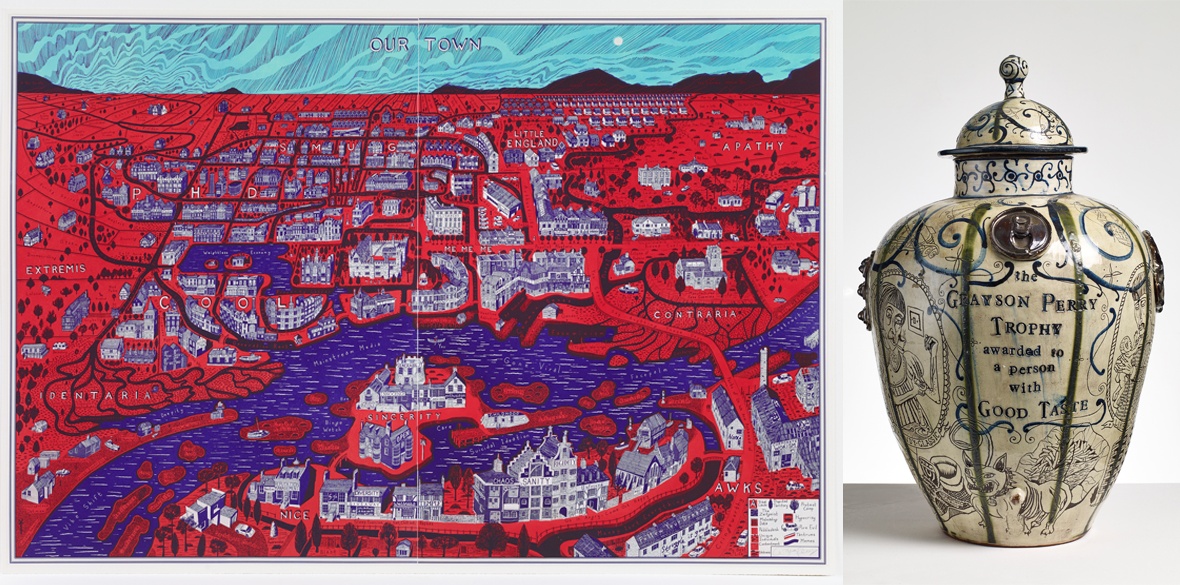

Smash Hits features work from his early days at art school through to the present day, effectively grouped thematically rather than by date, though the layout of the Academy’s rooms can leave one going round in circles that resemble Mendick’s nightclub. Growing up on a council estate in Essex, Perry began dressing in women’s clothes as a teenager while fearing the retribution of his violent stepfather. His subversive and playful approach to pottery destabilised the form’s reputation as refined and middle-class, and attracted a level of art world snobbery before he won the Turner Prize in 2003.

We see his continuing class dysphoria in especially in his tapestries — an art form Perry came to late in his career, but which he has made his own — which have allowed Perry to expand the narrative aspect that has always characterised his vases. His 2012 series The Vanity of Small Differences adapts William Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress in the moving life story of a tech entrepreneur whose class trajectory bears some resemblance to Perry’s own.

Death of a Working Hero is a striking piece inspired by the banners of the Durham Miners’ Gala, and is inscribed: “We work for the future and grieve for the past.” It’s a message that seems oddly upside down, and Perry’s accompanying description of “an annual celebration of the fading legacy of heavy industry, left-wing politics and working class culture” rather misses the point: Durham still exists only because it has become a celebration of an active and resurgent working-class movement.

But this knight of the realm remains one of Britain’s most interesting living artists precisely because — in spite of his co-option by the Establishment — he is still prepared to provoke, and prepared to be wrong in order to be true. Much of his greatest work here was produced in service of television series for Channel 4.

One can’t help but wonder how many younger working-class artists will ever be offered that opportunity. Repression takes many forms.

Grayson Perry: Smash Hits, at the National Galleries of Scotland: Royal Academy, until November 12

Lindsey Mendick: SH*TFACED, at Jupiter Artland, until October 1

Conrad Landin

Conrad Landin