This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

“THE race to find bigger and better ways to destroy each other is a terrifying prospect, one which has never left the public consciousness for 70 years,” says artist John Marc Allen.

Currently running at Blackpool’s Hive, How I Learned to Stop Worrying is Allen’s enlightening and provocative exhibition on the human capacity for planetary destruction and the mass psychology underpinning it.

Nuclear conflict invaded Allen’s thinking at the age of 10, in the form of Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s Two Tribes. The nine-minute Annihilation Mix (1984) included lines from the government’s Protect and Survive campaign, such as: “If your grandmother or any other member of the family should die whilst in the shelter, put them outside, but remember to tag them first for identification purposes.

“That’s pretty scary stuff to take in, especially at that age, but it’s one of my favourite songs of all time,” says Allen.

The past few decades have seen a proliferation of existential threats, but “The Bomb” remains a potent creative stimulus. Consider the critical and audience interest in Oppenheimer, the Christopher Nolan film, and Benjamin Louboutin’s novel, The Maniac. The Manhattan Project, and the notion of scientists becoming “Death, the destroyer of worlds,” is central to both stories.

Allen believes our obsessive interest stems from a single factor: “The finality of it. The threats of climate change and the ever-widening gaps between the wealthy and the poor are slow-burns. They have taken decades to manifest and may take decades more to realise their full impact on humanity, although I think we’re doing a good job at speeding up the process.

“There’s no coming back from The Bomb — going out with a bang, not a whimper. The continuing tensions between East and West echo those of the ’60s and ’80s, when the threat of nuclear conflict felt very real and very influential on popular culture.”

A striking aspect of the exhibition is the incongruity of theme and style. Allen’s text, images and installations are unflinching in their representation of catastrophe, but his use of a Pop Art aesthetic affords a degree of accessibility, irony and charm.

“Pop Art is immediate and attention-grabbing,” he says. “Initially, I thought it would be jarring and funny to do a series of paintings in a gaudy Pop Art style — bright colours, glitter — about the most serious of subjects.

“Warhol’s Death and Disaster paintings, of the electric chair, car crashes and so on, were definitely an influence, a way of desensitising the viewer to terrible things by means of repetition and aesthetics. As I researched the subject more deeply, some of those ideas were tempered a little, but they still ran through the project.”

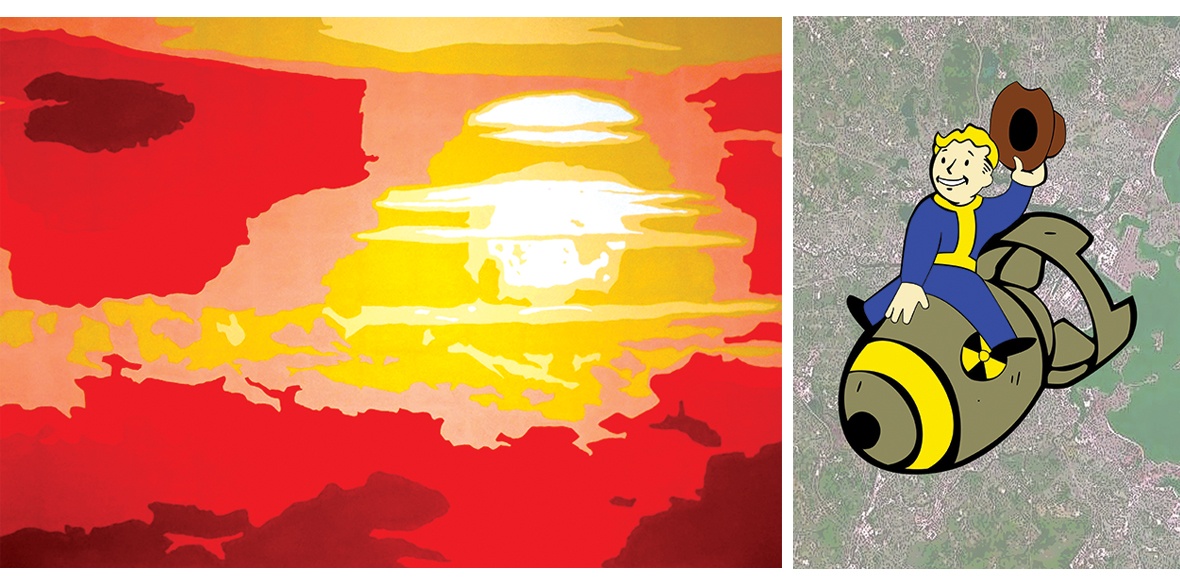

Many of Allen’s exhibits reconfigure material from popular culture. There’s a retro-gas mask in spray paint and maker pen, resembling a medieval plague doctor’s mask; a cartoon image in flat primaries of Vault Boy from the Fallout game franchise, who re-enacts the bomb release scene from Dr Strangelove; a spray-painted film image; and a range of digital transformations of maps, toys, posters and graphic novels.

The process of re-editing images is a well-established part of Allen’s creative practice.

“Using established imagery, in the classic Pop Art style, is the perfect way to draw people into the work. Hopefully they find a deeper appreciation of what I’m trying to put across. Not that I’m Warhol, but it’s easy to dismiss his soup cans, until they draw you in and you understand the story he was trying to tell you.”

The exhibition is based on thorough research from a range of sources. Extracts from the 1970s Protect and Survive campaign are accompanied by abstract representations of air attack warning signals in acrylic on canvas.

Statistics relating to the bombing of Hiroshima are illustrated with a pencil drawing of the city’s ruins. And details of the forgotten and disastrous Castle Bravo thermonuclear weapons test of 1954 are accompanied by a large semi-abstract painting, based on a constrained palette of yellow and red. This can either be seen as a pleasant Pop-style sunset or an ominous fireball.

“I don’t think I’ve even scratched the surface of the information out there,” says Allen. “It was interesting to delve into this theme and discover how broadly it can reach — searching through archival websites for factual information and looking for more ephemeral aspects. One day I’d be looking up the explosive yields of nuclear weapons tested in Nevada, the next I’d be finding out the history of the Bikini (the swimwear was named after the nuclear testing location).

“A Netflix documentary series about the cold war has given me a whole new insight into how the bomb has shaped — and is shaping — the global political climate. As long as we’re all still here, I think I’ll be finding out something new.”

But is delving into the history of The Bomb helping Allen to stop worrying?

There is, he reminds me, little comfort to be drawn from the ending of Dr Strangelove: “The final shots, to the strains of We’ll Meet Again show us that we most definitely won’t meet again.”

How I Learned to Stop Worrying runs until May 30 at The Alternative Gallery Space @ HIVEArts, HIVE, 80-82 Church Street, Blackpool. Open Tuesday-Saturday 11am-4pm.

The book of the exhibition, How I Learned To Stop Worrying, published by Tangerine Arts, is available at Hive, or from www.thegreatbritishbookshop.co.uk.