This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

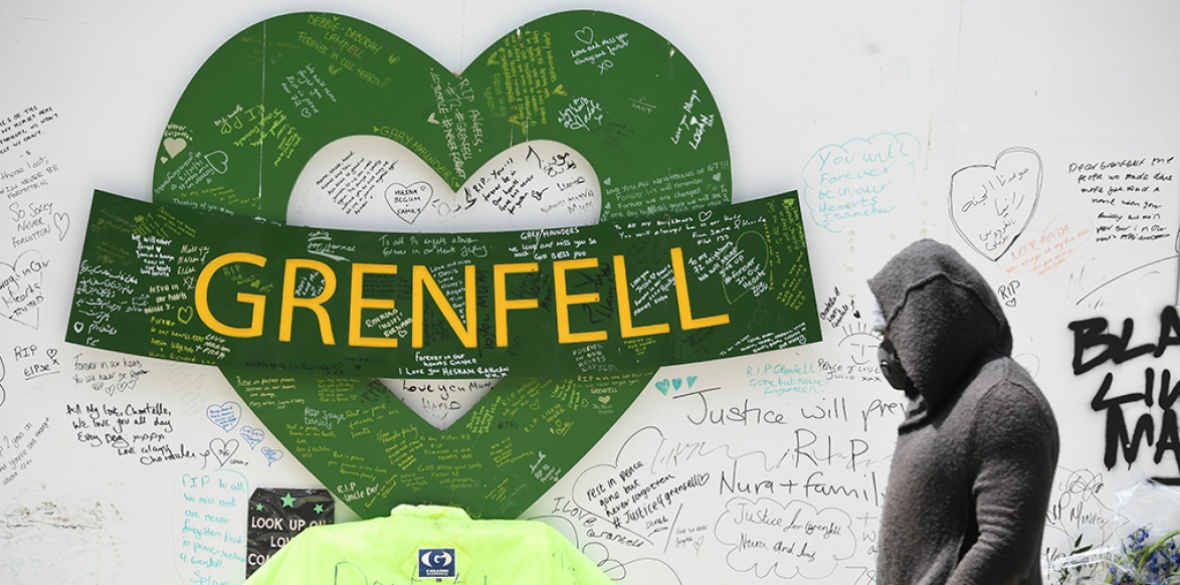

SEVENTY-TWO men, women and children died on June 14 2017 in the Grenfell fire disaster.

On August 15 2017, the Grenfell inquiry was set up to understand the circumstances around the fire.

The Metropolitan Police opened one of the largest investigations into allegations of corporate crime.

Grenfell Tower was bereaved. Survivors’ and residents’ groups have said that they will not settle for anything less than prosecution.

Over the past three weeks, the inquiry has heard evidence from former employees from Celotex — the manufacturer of plastic insulation RS5000 used within the Grenfell cladding system — who told the Grenfell inquiry how Celotex deliberately and dishonestly rigged tests, defrauded test houses, manipulated data, abused compliance procedures and misused test certificates to get the combustible plastic insulation product approved for use in high-rise cladding systems.

The inquiry was even told how Celotex offered a compliance audit offering to check cladding designs and specifications.

Celotex advised clients that systems which had never been tested were “approved for construction” based on the fraudulent tests.

Attorney general Suella Braverman QC was heavily criticised by Grenfell groups when she gave an undertaking to protect corporate core participants from self-incrimination.

But without the controversial undertaking, it’s highly unlikely that the inquiry would have been able to extract candid comments from corporate witnesses.

A spokesperson for the attorney general said: “It is without question true that there is no immunity from prosecution.

“The attorney’s decision does not jeopardise the prospects of a successful prosecution.

“That, of course, means a successful prosecution by way of a fair trial. There have been many similar previous inquiries that resulted in fair trials — ie Abu Hamza, Rebekah Brooks and David Duckenfield.”

The Grenfell cladding design comprised of Celotex RS5000 insulation and a Reynobond PE aluminium composite rainscreen panel. On paper, it seemed as though the cladding complied with a raft of regulations.

But it didn’t.

The Building Research Establishment (BRE) provides test services and awards BR135 performance classification.

BRE says: “A cladding system that performs to the criteria in BR135 … is taken to meet the fire safety requirements in the Building Regulations 2010.”

The inquiry heard how Jonathan Roper joined Celotex in 2013 as an assistant product manager.

He was quickly promoted and tasked with finding out how Celotex’s competitors Kingspan had managed to get their K15 insulation passed for use within aluminium rainscreen cladding systems on high-rise buildings.

Roper quickly realised that Kingspan had only tested its product in a very robust non-combustible cladding system.

He asked the BRE how it was possible that Kingspan could use that certificate to prove compliance for a much wider field of application without further fire safety tests.

The response from Stephen Howard, director of fire testing and certification at the BRE, placed the onus on the building owner and building control to ensure a system is covered by a test result.

Roper told the inquiry that Celotex knew that RS5000 could not obtain BR135 classification within an aluminium composite panel, the cladding used on Grenfell.

He told his bosses: “The Celotex product realistically should not be used behind most cladding panels because in the event of a fire, it would burn” (November 2013).

Undeterred, Celotex sought the advice of the BRE on how to pass a BS8414 test and have RS5000 classified as BR135 compliant.

On February 14 2014, BRE undertook a BS8414 cladding test with RS5000 and an 8mm Marley Eternit cement particle board.

It didn’t go well, and the test was stopped after just 26 minutes when flames from the burning insulation reached the top of the test rig.

Phil Clark, senior consultant at BRE, was present throughout.

Roper claimed that Clark “suggested that Celotex might want to strengthen the outside of the test rig in order to counteract the cracking of the particle panels.”

Celotex decided to use a thicker 12mm Marley Eternit particle board, introducing a 6mm fire-resistant magnesium oxide board to protect electrical devices called thermocouples which were installed to measure how hot the system got.

The additional material allowed the combustible insulation to pass on the second test because the thermocouples recorded a satisfactory temperature within the cladding system.

This data was key to obtaining BR135 classification and other industry standard approvals.

A decision was made — Roper believed at board level — to exclude references to the addition of the crucial magnesium oxide board from the BRE report detailing the results of the test and marketing materials.

Roper told the inquiry: “With the benefit of hindsight it seemed to me that Celotex was going down the Kingspan route in not giving full details of the system that had been tested.”

On May 15 2014, Roper emailed the National House Builders Council (NHBC) informing them that RS5000 had successfully gained BR135 classification.

Roper recalled that the NHBC criticised the test saying it was “deliberately over-engineered.”

Roper explained to the inquiry that “the NHBC wanted to see Celotex test with an aluminium composite panel, but we believed that an ACM panel was likely to melt.”

Throughout 2015, NHBC opposed the use of plastic insulation in cladding systems.

Ivor Meredith, a former technical manager for Kingspan, revealed that Kingspan threatened NHBC with an injunction when the guarantor threatened to refuse to sign off buildings which had included Kingspan K15 in the cladding.

The NHBC capitulated and approved the use of both Kingspan and Celotex insulation materials for use above 18m.

Roper emailed bosses saying that “I’ve also got Local Authority Building Control involved to issue a report stating Celotex can be used behind a variety of systems above 18m to prevent any challenge from building control.”

In May 2015, lab-based testing company Exova undertook a desktop study for Celotex to assess how RS5000 would perform with a range of different panels which had the same classification as the Eternit boards used in the successful test.

Exova was asked to assess if RS5000 coupled with an unbranded aluminium rainscreen panel would meet the test for BR135 classification.

Exova wrote: “Compared to the tested construction with fibre cement boards, the insulation material and fire breaks are exposed to a more intense fire situation.

“The effect of this increased exposure is difficult to quantify but it could result in a more intense burning of the insulation material and possibly a failure of the fire breaks.”

Exova concluded its report saying that pairing RS5000 with an aluminium rainscreen panel “can’t be judged with certainty to meet the performance requirement as outlined in BR135.”

A spokesperson told the Morning Star: “Celotex was obliged at the time to disclose all the details of that test (BS8414) to Exova.

“It has since accepted that it did not do so. As soon as it became known that there were doubts over the validity of Celotex’s BS8414 test incorporating its RS5000 product, Exova withdrew any assessments which included the product and notified the relevant customers, in line with industry standards.

“In the last month Celotex employees have given evidence to the inquiry which identifies further serious concerns in relation to the system which Celotex submitted to BRE for testing.”

Sam Stein QC, acting for the victims and survivors, accused the BRE of “reinforcing the dangerous and dishonest culture within the industry” and said: “Testing was inadequate and certification haphazard.

“By their failures, the testing and certification bodies contributed significantly to the Grenfell disaster.”

The inquiry asked Ray Bailey of Harley Facades Ltd which route to compliance was being followed on the Grenfell cladding.

He said: “There was a BS8414 test, so it was a material that had had a whole series of tests, it was a fantastic product.

“On the certificate, we saw that it said it had been tested with different facing material.

“We sent our details to Celotex to get them to sign off that it was safe. So, I suppose we’re saying we believed that Celotex had carried out a study on it.”

Justice 4 Grenfell said that Celotex “felt confident to pass off fake tests, mislead customers and could function within a failed system of oversight and/or governance.

“They knew what they were doing was dangerous. But their risk-taking for profit was far more of a priority than those facing the greatest risks — the lives of the working-class residents of the tower.”

Justice 4 Grenfell added: “This does not look like simple matters of fatal cheating and greed on a single project due to a one-off management or product failure or ‘bad individuals’ cutting corners on a job.

“This looks more like a systematic and greed culture within the building sector; where it was known that there was no strict regulatory body that they need to be accountable to; and what is more blatant is the ‘chumocracy’ culture of the industry.”

A spokesperson for the Department of Communities and Local Government told the Morning Star: “Together, the Fire Safety Bill, the draft Building Safety Bill and the fire safety consultation will create fundamental improvements to building safety standards and ensure residents are safe in their homes.”