This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography

Tate Modern, London

THE Tate Modern show, A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography, is an important exhibition on a number of levels.

The photographs portraying the diversity of this wonderful continent themselves are startling and help to liberate photography into being an ally in the cause of undermining the generations of negative portrayal of black people.

Showing everything from biker gangs in the North of Africa in Marrakech, to gay picnics in South Africa, to Cameroonian landscapes, and capturing the hustle and bustle of the streets of Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo does what most attempts to portray this giant continent fail to do — show its massive diversity.

How best to select the artists to represent the continent of more than a billion people in all that diversity is no small task.

I was impressed throughout that the 36 artists on show were able to carry through that representation.

This is very significant for any black person going to an exhibition about the continent from which we are descended. Far too often we have turned up to cringe-worthy or insulting depictions of this wonderful continent.

We have had enough of being treated as primitive creatures whose history began and ended with the trade and enslavement of our ancestors across the sacred burial grounds of what is known as the Atlantic Ocean.

I have visited many exhibitions relating to Africa or about us black folks and too often wanted to find the fastest exit before I screamed or got arrested for criminal damage of an exhibit.

Nothing like that here.

I found myself going back round the exhibition to experience photographs again, and wondering whether I might conceivably be related to anyone in the pictures — something I will never know.

I was particularly drawn to the section in the exhibition on masks.

I know from DNA tests that on my mother’s side I am a descendant of the Tikar people who are thought to have originated from beside the River Nile and are now currently to be found in Cameroon.

The Tikar people are renowned for their excellent and highly detailed masks.

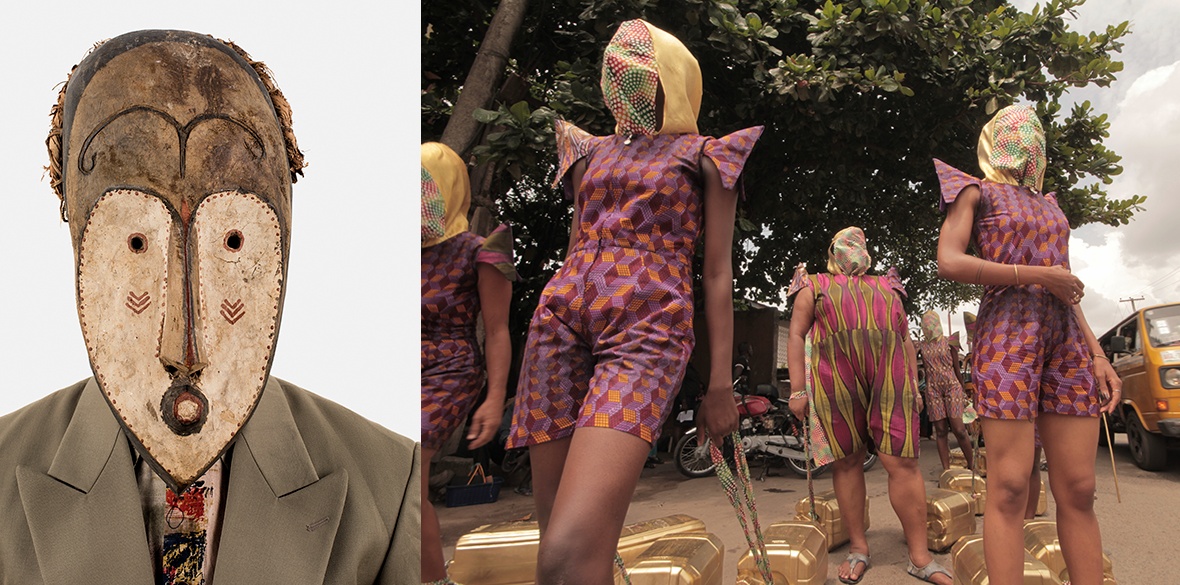

The series of images by Angolan photographer Edson Chagas, called Tipo Passe, Portuguese for passport, kept calling me back for another view.

It’s particularly important for someone from what is now known as Angola to explore the spirit of the ancestors as Edson Chagas, the Angolan photographer does, given that more people were enslaved from that part of the continent than anywhere else — mostly ending up in brutal plantations in Brazil.

The brilliant photographs by Chagas are of a variety of traditional Bantu masks posed exactly as if for a passport photo, and for each subject he gives each an invented European-African name, such as Cheick F.Ouattara and Pablo P Mbela, to highlight the impact of migration, colonialism and, of course, enslavement.

Chagas shows the different meanings attached to masks by Africans and Europeans.

He explains that: “The real or assumed identities of the people hidden beneath the masks are given, whose European-derived names associated with local surnames, recall Angola’s long past as a colony.”

Alongside the gallery devoted to masks were also a couple of fantastic video films.

A film by Zina Saro Wiwa, who is the daughter of the late Nigerian writer and human rights activist, Ken Saro Wiwa, shows herself in a variety of masks which make her either more or less visible — feelings that black people often go through during our lifetimes in the face of racism.

The Wura-Natasha Ogunji video Will I Still Carry Water When I Am A Dead Woman? showed a line of masked women hauling heavy gold-coloured water canisters along the rough ground of a Lagos district.

I noticed at one point that a “real” local woman carrying what was clearly a heavy load balanced on her head passes the “performance” without the time (or probably energy) to even turn and acknowledge what was happening.

The spiritual section shows work by the Senegalese artist Maimouna Guerresi.

An incredible five-panel piece shows an old man in a high black hat reading Sufi scriptures to four young women dressed in bright red, perched on black blocks round a table with a shell case and petrol can on it.

And it is very important to note that the photographs throughout the exhibition never portray Africans as victims.

Of course the photographs and videos do not avoid the brutalities of enslavement and colonialism, but I was struck by how the photographs throughout gave agency to Africans in a way that is rarely seen.

A sense of pride and determination not just to survive but to thrive came across to me in every section of the exhibition.

That is why attempts to supposedly “decolonise” the lens are so important.

The exhibition helps us to look deeper into the role that photography plays in manufacturing competing views on race.

It can help to give strength to black people like me struggling in a world that constantly tells us that we are “lesser” and where any slight mistake is pounced on far more than it would be with a white person.

Alternatively, exhibitions on Africa and black Africans can often serve to reinforce the belief that Africans are subhumans to be pitied and mere victims with no worthwhile history or contribution to make.

This exhibition thankfully is very much the former and can help white people to confront their own misconceptions and prejudices about Africa.

So, I encourage you to visit A World in Common and, more than that, enjoy the area outside the exhibition in the place called Common Ground, and discuss what you have just seen.

Multidisciplinary artist Ronan McKenzie (no-relation as far as I know) created this area as a “place to gather, reflect and relax” after the exhibition.

He says he hopes the space will help to “ignite ideas.”

It did for me! How about a similar exhibition based on the diversity in the lives of Africans across the diaspora? From Handsworth to Marseilles. From Kingston to Rio. From Cali to Chicago.

Maybe it’s already been done and I missed it. Never mind. Do it again. There are plenty of stories to be told.

This is a first-class exhibition. Tell your friends, and go and see it — then tell more friends about it.

Runs until January 14 2024. For more information: Tate.org.uk