This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

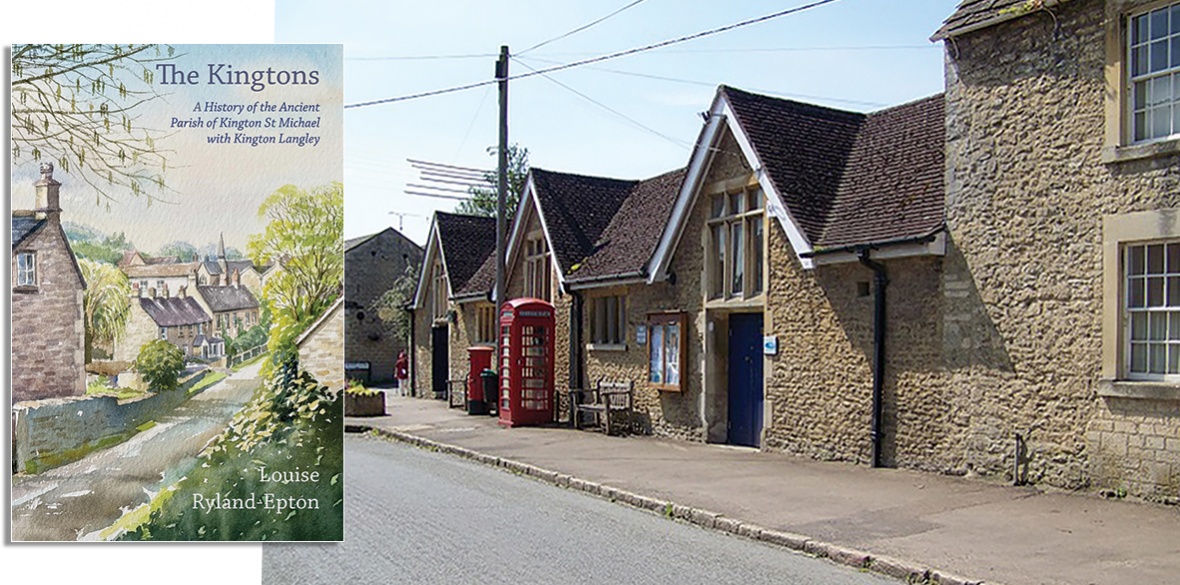

The Kingtons: A History of the Ancient Parish of Kington St Michael with Kington Langley

Louise Ryland-Epton

Hobnob Press, £14.95

IN 2015 members of the national press descended on the small village of Kington St Michael in Wiltshire looking for dirt on the then leader of the opposition, Jeremy Corbyn. Alas for them there was little memory of the socialist family that had lived in the village in the 1950s. While a Cllr Corbyn had left their mark in the minutes of the parish council, the family had moved out by the time young Jeremy was seven.

Had the press decided to do actual research they might have found numerous more interesting stories of life in this slightly isolated rural parish that stretches back 1,000 years. Louise Ryland-Epton does the hard archival work in this excellent book and uncovers real lives and a changing community with a degree of granularity that bigger histories often overlook.

First defined in 940 as an estate providing the royal Saxon household, Kington St Michael has a number of peculiarities. St Mary’s Priory was one of two medieval nunneries in Wiltshire (the other being in the more popular tourist destination of Lacock). The parish was also the birth home of notable scholars John Aubrey (1626-1697) and John Britton (1771-1857), who are both detailed in case studies.

Agriculture was the primary occupation throughout this period, with most workers in various forms of obligation to both the church (Glastonbury Abbey) and manorial estates.

Ryland-Epton admirably focuses on the role of women in the local economy. Not only did the local nuns teach local girls to write and draw, it also provided a home for vowesses who refused to remarry.

Unusually the prioress had the right to raise the gallows for the village. In an era when men acquired their wives’ inheritances, some women were able to retain their property. Edith Brown ran an alehouse and refused to remarry when her husband died. Despite being accused of witchcraft by a rival brewer, she was able to run a business in Elizabethan England for over 20 years.

Tax records show that no-one was particularly wealthy in the villages for centuries. Things began to change with the dissolution of Glastonbury Abbey, when the estates passed into private hands.

Social life focused on the seasons, church festivals and revels, but a bygone Archers it was not. As well as disease and poverty — managed by parishes and charitable foundations — there was also religious persecution and crime, with the first murder recorded in 1249 and local scandals as squires wriggled out of crimes of passion.

Occasionally the villagers enjoyed a good tear-up, often accompanied by drink. After the 1822 Kington Langley revel, villagers had become agitated by the conduct of Chippenham men and invaded the nearby town carrying bludgeons. Two men were murdered and 31 injured. Twenty were arrested, but the two prosecuted for murder were acquitted for lack of evidence.

Ryland-Epton makes great use of John Aubrey’s works, and the book is richly illustrated with his drawings as well as those by John Britton and Heather and Robin Tanner from the 1930s. Images from the National Portrait Gallery and the Society of Antiquaries, many of which would have otherwise only been seen by a specialist audience, add to the book.

Many further themes are explored including education, the villages in wartime, superstitions (including ghosts), the squirearchy and the church. Very much a local history, it focuses on everyday inhabitants for whom national events are significant, but not overwhelming.

There is much merit in examining history with this level of local detail.

In his “forgotten” history of the black population of England, David Olusoga recounts a 1762 advertisement from John Stone, in Chippenham, offering reward for the return of his absconded black slave, while also threatening to prosecute anyone found harbouring him. One wonders how that story resolved itself locally in deepest Wiltshire, and what else there is discover in the stories of the small, and often considered insignificant, areas of the world.

Ryland-Epton delivers a model of local historical research, which is easy to read.