This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

I AM convinced speculative fiction — the narrative exploration of “what-ifs,” the creative probing into latent possibilities, the imaginary voyaging into potential futures — is the genre of our times, certainly in areas like the environment but also politics, economics.

This, the first, collection of Australian First Nation voices exploring these very questions through storytelling is a most welcome addition to the scene.

What makes this volume distinctly First Nations is the term Country — something utterly fundamental and intimately related to the self and is centrally present across these pages.

It’s often is restorative such as in Larrakia, Kungarakan, Gurindji (both people of the Northern Territory) and French writer Laniyuk’s Nimeybirra you read: “I want justice. I want retribution. I want vengeance. I want the ugly. I want the wrong. […] In the quiet calm, in conversation with Country, I hear the whispers of another way of being, and that is the call I must follow. That is the only reason and voice that makes sense in the world.”

Throughout the book, Country’s ever presence is suggested in little phrases or metaphors, it’s there in myriad deeply meaningful references to smoke, birds, sand, water, wind, light, air and trees.

Sometimes, the contrast between a story’s setting and Country is incongruent, but at first glance only. A gripping example is Nyungar (language of the Noongar, who live in the south-west corner of Western Australia) technologist and digital rights activist Kathryn Gledhill-Tucker’s startling piece Protocols of Transference.

It consists of shards of monologue directed towards an unspecified electronic technology, from when it “first spoke” to its final days.

The narrator observes that the collapse predicted by data that had “overwhelmed our scientists” was “avoidable, had they paid attention to our country and kin” and … “by country and kin, we mean all of it. We encompass the ground and all its substrate, sand, rare Earth minerals, craters left from old meteors that make their way into old stories, hidden river systems, animals fossilised in place, tracks tracing paths from trees to waterholes; trade routes and songlines that have made way for worn paths, widened by horses, then lanes of cars, paved with bitumen, that leave scars of old stories in the geometry of people and protocol.”

Another recurring element in this anthology is a playful humour. Noongar writer Timmah Ball’s An Invitation is set in a time that references the “era before buildings disappeared.”

This humour is impertinent and tongue-in-cheek, as shown in Gomeroi (people of what is now New South Wales and southern Queensland) poet Alison Whittaker’s The Centre: “I remember my first time in the digital coolamon” (a coolamon — anglicised NSW Aboriginal word — is an carrying vessel used by Aboriginal women to carry water, fruit, nuts, as well as to cradle babies.)

In Pakana (Aboriginal of Tasmania) award-winning writer Adam Thompson’s Your Own Aborigine, a “Sponsorship Bill” requires Aboriginal people to be personally sponsored by an Australian taxpayer in order to receive welfare money.

In Five Minutes, Kalkadoon (peoples living around Mount Isa region of Queensland) writer John Morrissey mocks the European settlers connection to Country (200 years) as compared to Aboriginal Australians (50,000 years) while aliens invade.

The ETs incinerate settlers in an instant — but apologetically grant Aboriginal people an extra five minutes to say goodbye to Country.

Wonnarua (peoples of Hunter Valley area of NSW) and Lebanese author Merryana Salem’s play on temporalities in When From? — a story about a clandestine time-travel mission, in a world where time travel is possible but has been banned, to collect “reference footage” of frontier violence, for historical accuracy in filmmaking.

When the traveller, Ardelia Paves, is instructed not to interact with “the population,” she protests that “they’ll be massacred,” but is told: “Even if you were permitted to interact with the population, Miss Paves, how would you warn them? Last I checked, the dialect was lost.”

Finally, what sets this anthology apart is a unique exploration of its “what-if” premise — each story is connected to its precedessor through one theme and to its successor through another: they come together like notes in a song. This is due to Koori (people of south-eastern Australia) writer and editor Mykaela Saunders’s exceptional editing.

While there are many original voices in this anthology, it also speaks with one loud and proud overarching First Nations voice.

A must read for anyone who might wonder what a First Nations response to the question of our potential future might look like.

Yasmine Musharbash is senior lecturer and Head of Anthropology at Australian National University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

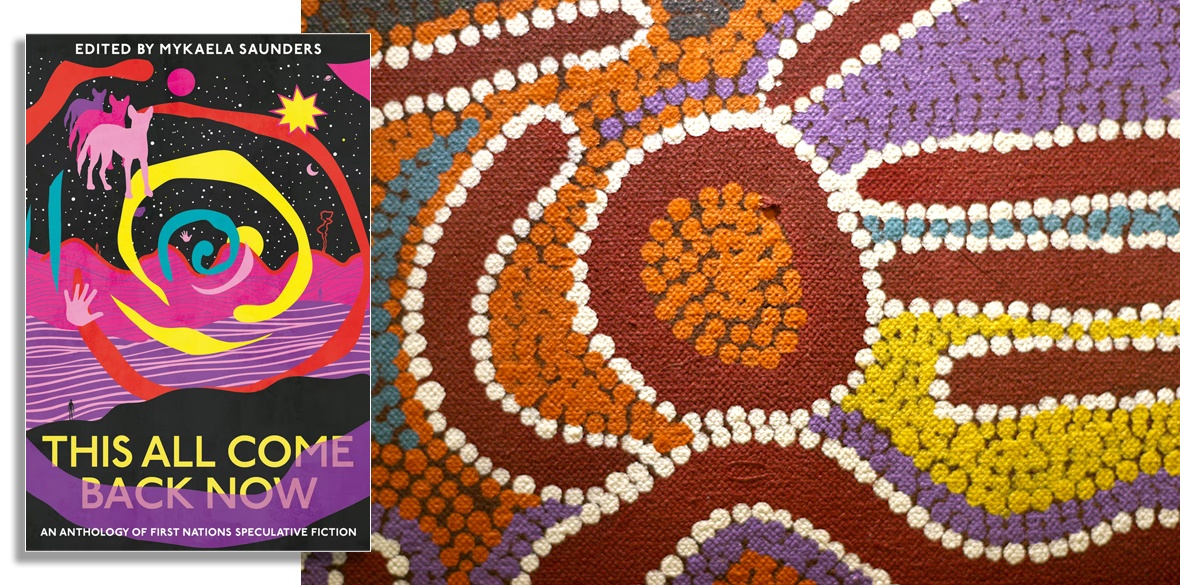

This All Come Back Now: An Anthology of First Nations Speculative Fiction edited by Mykaela Saunders has just been published by University of Queensland Press.