This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

VIDEO games add more to the British economy than film, TV, music, publishing, design, fashion and architecture combined.

In 2019, some 18,279 game developers contributed a staggering £2.2 billion to the country’s GDP — an increase from £1.8bn the year before.

The growth is looking exponential, and it shows no signs of abating. More and more workers are flocking to development studios, PC gaming is up 46 per cent, and mobile gaming, 17 per cent.

In fact, a 2020-21 survey showed 92 per cent of adults aged 16 and over are already playing video games, while projections for 2025 suggest the number of video game users in the UK will reach 51.88 million.

If the population reaches the estimated 68.3 million mark, that will be 75 per cent of the nation, actively engaging in digital, interactive entertainment.

The figure is impressive globally too; 3.5 billion people around the world will soon be video game consumers — in other words, approximately half the planet.

This embarrassment of riches is often lauded by business leaders and politicians as an entrepreneurial success story, made possible by competition between creatives in a capitalist society.

Never mind the awkward truth that this multibillion-pound industry was founded by a group of self-professed hackers who stole time and resources from the US’s military-industrial complex to prototype gaming machines.

The origin of video games is linked to a technoscientific cognitariat that the US’s powerful defence corporations failed to control.

Through channels like the Advanced Research Projects Agency, vast sums of money entered research centres in a bid to steer the first mass draft of immaterial labour in the US towards preparing for a nuclear conflict with the Soviet Union — and we have video games because a little of that money was misappropriated and put to better use.

Perhaps this goes some way in explaining the military’s interests in the gaming industry, and how it was able to exercise its influence so quickly. By liberating computers and video games from the Pentagon, hackers inadvertently set the stage for their “reterritorialisation” by capital in pure commodity form.

In Britain, attempts to bring gamers into the military’s fold are openly acknowledged and play a part in recruitment propaganda.

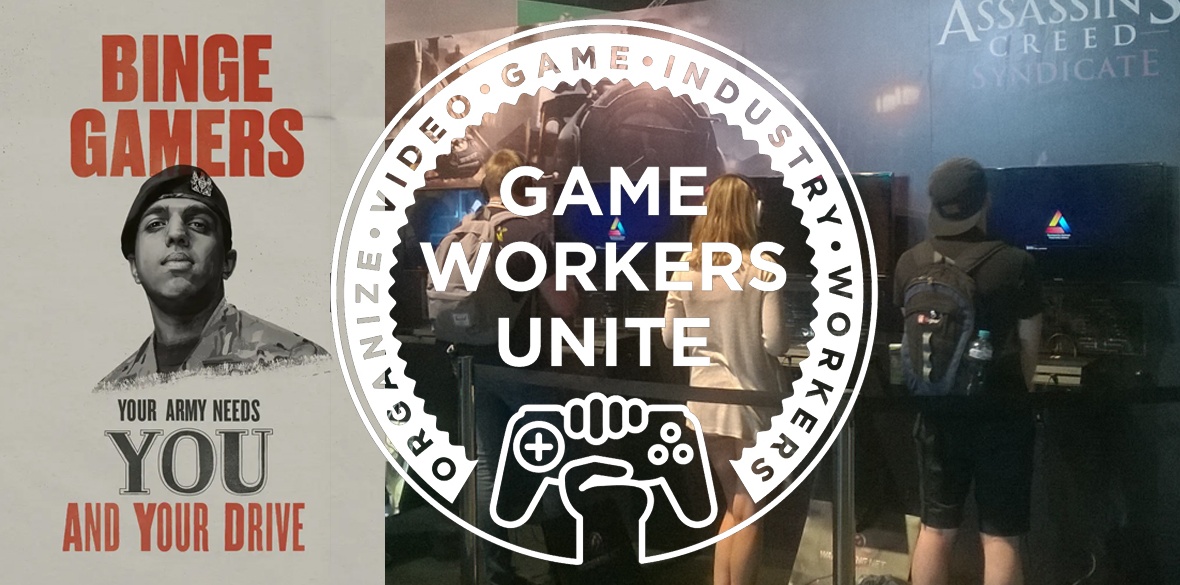

The British army’s latest advertising campaign demonstrates this perfectly with posters reading: “Binge gamers, the army needs you and your drive.”

In reality, video games themselves are working as a primer. Many sanitise and glorify modern warfare, normalising violence while promoting nationalistic notions of who our enemies are.

This usually involves framing “good guys” as freedom-loving US special forces and “bad guys” as generic Middle Eastern terrorists. Or Iranians. Or nowadays, the Chinese or Russians.

As a video game developer myself, I have seen first hand how studio executives will push false narratives and politicise creative content.

Anti-Marxist sentiments are often mandated from above and historical events are regularly revised before being insidiously presented as fact.

Combined with this, for the sake of authenticity, game writers and designers are routinely paired with military consultants, who can also prove instrumental in pandering to conservative paranoias.

Moreover, video games have also been targeted for product placement by major gun companies, which hope to reinforce their brand identities and have their merchandise showcased in realistic combat scenarios. In this respect, video games are appropriated as interactive promotional materials.

And how do those battles affecting game developers in the workplace?

Compulsory overtime is almost expected in the industry. Known as “crunching,” it is a cost-cutting exercise that can lead to 80-hour weeks for extended periods of time, without extra pay.

This frequently results in “burnout,” a catch-all term to describe the myriad health problems occurring when studio employees are pressurised into working day and night in stressful circumstances.

I can testify to this from personal experience and have been compelled to crunch for months on end: once, for 96 hours straight.

Aside from this gruelling practice, thousands of others also face gender discrimination, bullying and sexual harassment.

In the words of a fellow freelance narrative designer Meghna Jayanth, “[It’s a] confluence of worker disempowerment and a male-dominated managerial class [that makes game development] an especially unwelcoming place for women.”

The industry “sits at the intersection of the worst of the casting couch, predatory networking culture of the entertainment industries, and the unregulated boys’ club mentality of Silicon Valley. There’s an entire culture of silence, complicity and even enabling toxic behaviour.”

But of course, workers have not been idle in resisting these conditions.

Over the years, many high-profile cases have appeared in the press and inspired efforts to establish unions. In 2018, a British chapter of the international Game Workers Unite union was legally recognised as a part of the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain.

The first labour association in the country to represent the interests of game developers, its goals are to end unpaid overtime, to educate and protect targeted workers, to improve inclusion and diversity and to establish fair and regular wages.

In practical terms therefore, the familiar question of “what is to be done” may be easily answered. Those of us developing video games in Britain should join the Game Workers Branch of the Independent Workers union of Great Britain and encourage others in the industry to do the same, while championing and sharing information on the organisation’s campaigns.

Political education and further reading should also be considered, especially Marx at the Arcade by Jamie Woodcock and Games of Empire by Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter.

And in terms of our response to capitalist cultural hegemony and video games, we must strive towards a more daring and creative solution.

The ruling classes, in an impulsive attempt to secure and further the runaway profits of the gaming industry, have left the gate of their falling castle unguarded.

By spurring automatised software, generous government subsidiaries and free digital distribution services, they have unintentionally provided us with the means to confront the social, political and economic status quo.

Now is the time to fight back, as artists — real artists, leveraging the power of virtual play with passion and integrity. Not alone but together, as Marxist game developers.

To do this, we have to combine our skills and resources and establish at least one video game studio, run as a workers’ collective for peace and socialism.

It will require experienced and dedicated comrades and it will also require outside support, from the Game Workers Branch of the Independent Workers union of Great Britain and from communist parties, internationally.