This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

“BRUTALISM” — the greatest misnomer in cultural vocabulary today — is in fact quite the opposite. An architecture of care, it embraces humanism, solidarity and unbridled imagination and by definition is participatory, aspirational and inherently democratic.

It hasn’t always succeeded aesthetically but as an endeavour it has had universal appeal for decades.

When Margaret Thatcher — a stalking horse for the characteristic political brutality and myopia of neoliberalism — announced that “there’s no such thing as society,” it was the end of the line for the architecture of municipal housing intended to address the needs of ordinary people in housing, healthcare, leisure or public administration.

Yet interest in so-called brutalist architecture has been rekindled most recently as the odious wrecking-ball policies of globalised neoliberalism have proved to be just another of history’s many cul-de-sacs.

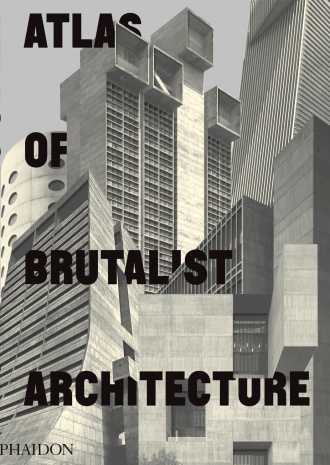

As is customary with Phaidon’s architectural series, The Atlas of Brutalism is a visual feast. It is a global journey of hope and no little awe at the sight of the well-known, and often spectacular, alongside the forgotten gems. Included too are a few demolished examples such as John Bancroft’s Pimlico School or Basil Spence’s Hutchesontown C estate in Glasgow.

The message of this beguiling visual testimony, in black and white throughout, is the living legacy of an architecture not for profit but social purpose, for the many. Each page is a rare visual adventure and the wow factor is there in the breathtaking variation of form, limitless invention and joyous freedom only released when talent is put at the service of society.

Fittingly, the legendary 1929 Rusakov (Workers) Club in Moscow by Soviet mould-breaker Konstantin Melnikov is included and it’s worth noting that the young Berthold Lubetkin, famed for Sivill House, Finsbury Health Centre and Bevin Court with its legendary staircase, honed his exceptional skills in that period of revolutionary fervour and invention.

It was an era when a new reality was being sculpted worldwide in “liquid stone,” as Brazilian architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha liked to put it, while reminding us that: “There is no private space. If it’s space, it’s public.”

That public realm has been debased by the curse of the 21st-century’s privateer developer. The Atlas, while not offering solutions to ongoing despoliation, reaffirms the primacy of serving public need and aspiration in producing great architecture.

Civic courage and determination will be needed to lay new foundations for a future that the many are again ready to sign up for.

The book’s an eye-watering £100 but it’s one that should be in every public, school and university library.