This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

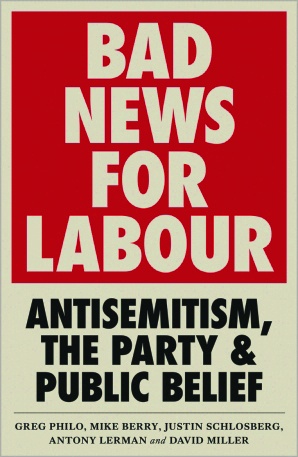

AS the political scene in Britain disintegrates in a toxic blizzard of insults, threats, hysterical claims and counterclaims, a still small voice of reason has emerged in the form of a new book: Bad News for Labour — anti-semitism, the party and public belief, by Greg Philo, Mike Berry, Justin Schlosberg, Anthony Lerman and David Miller.

Predictably, the launch of the book during the Labour Party conference in Brighton was disrupted by threats to the management and staff of the local Waterstones and had to be moved to another venue at the last minute.

Every other fringe event on the topic of Israel-Palestine was similarly targeted — a ploy wearily familiar to organisers of such events in Britain. As the prospect of a general election approaches, we can expect such attacks to become ever more frequent and febrile.

All the more refreshing, then, to read a calmly argued, fully sourced analysis of relevant facts.

Five professional analysts of the media and public opinion have looked in depth at the accusations of anti-semitism levelled at Jeremy Corbyn and the Labour Party since Corbyn became leader in September 2015 and at the response of both the party and the media. One statistic says a lot: from that date to April 2019 about 5,500 largely hostile articles were published on anti-semitism in the party — about four per day. No other issue has been accorded such prominence in recent times.

The timeline provided, which plots the ratcheting-up of the campaign, suggests some of the political motivation behind the onslaught. Many of the victims, such as Ken Livingstone, Jackie Walker, Moshe Machover, Chris Williamson and of course Jeremy Corbyn himself, were high-profile critics of Israeli policy and therefore obvious targets for the Israel lobby.

But the power struggles within the party also clearly singled Corbyn out for a no-holds-barred attack by right-wing colleagues.

The authors do not attempt a detailed critique of the party’s handling of the whole question. But the book does show how senior staff initially controlling much of the party machinery opposed Corbyn’s leadership and actively promoted the notion of “endemic” anti-semitism. The internal situation only began to improve after Corbyn’s success in the 2017 election.

The wider Establishment opposition to the socialist policies promised by a Corbyn-led government was to be expected. But the scale of the distortions and inaccuracies perpetrated in the Establishment-controlled media is staggering. In the period covered by this study, TV news programmes attacking the left of the Labour Party outnumbered those defending it by 4 to 1.

Moreover, the attackers went largely unchallenged, while the defenders were aggressively questioned and interrupted. When live interviews contained material supportive of the defenders’ view, this was usually edited out in subsequent broadcasts. Enormous publicity was given to allegations made by MP Margaret Hodge, but when it was shown that only 20 of her 200 alleged anti-semites actually turned out to be members of the party, the media were strangely silent.

On the contentious topic of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition of anti-semitism, TV, radio and the press were all referring to the definition as being “universally accepted” — when only eight countries in the world had in fact adopted it. Interestingly, the Sun, although having a strongly negative bias overall, is shown to have been more balanced in its coverage than the Guardian on this particular issue. When the respected Media Reform Coalition tried to engage with the editors on the Guardian’s coverage, the evidence presented was simply dismissed out of hand.

The question is, does such an avalanche of biased coverage affect people’s views? The results of a Survation poll carried out in March this year and focus groups from around the country suggest it does: it seems that on average people believe that a third of Labour Party members have been reported for anti-semitism — when the actual figure is less than 1 per cent.

The authors query the party’s response to the crisis. With so little actual evidence of widespread anti-semitism, one might think that it could have mounted a more robust defence.

On the contrary, it has shown itself all too willing to suspend members on the flimsiest of evidence and has not attempted to expose and pursue malicious accusers.

The reasons for this remain a mystery, to the authors as well as to the membership at large. It may be many years before the inner workings of the party at this time are disclosed. Then, finally, we may discover what on Earth has been going on.