This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

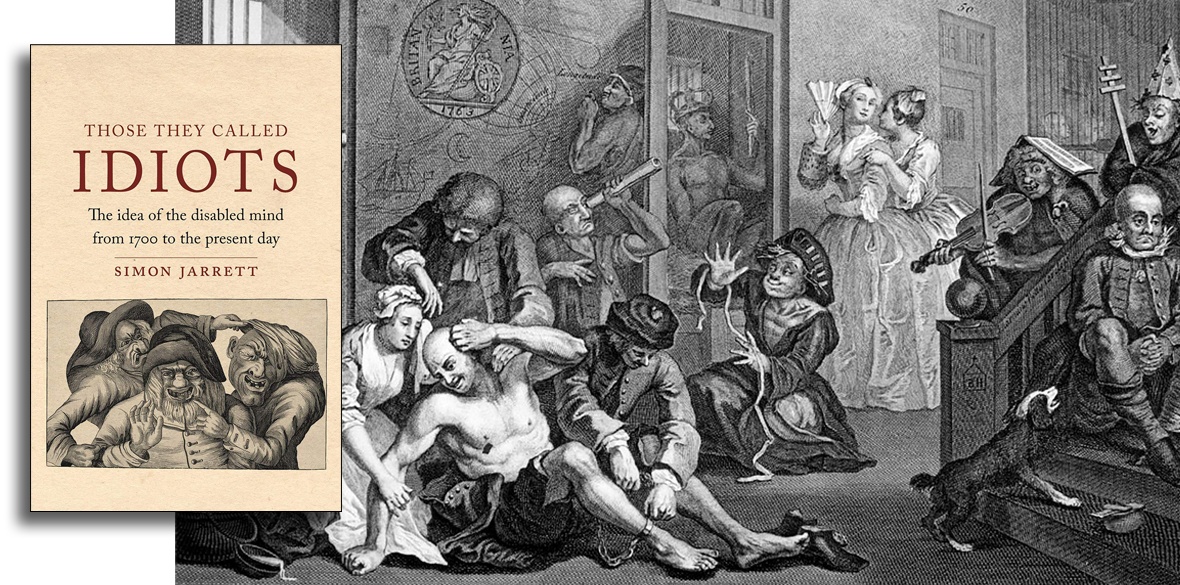

Those They Called Idiots: The idea of the disabled mind from 1700 to the present day

by Simon Jarrett

(Reaktion Books, £25)

IN RECENT years there has been a massive surge of interest in, and concern about, mental illness and approaches to it.

Criticism of those that are wholly biomedical and of institutionalised “treatment “rather than community-based support are very much mainstream points of view. Wariness of key pieces of legislation such as the Mental Health Act is no longer restricted to radical “anti- psychiatric” circles.

More broadly, there is a growing and wholly understandable awareness of the widening gap between what is considered best practice and what is actually delivered.

This hasn’t, however, been reflected in debate concerning those with learning disabilities. This is surprising, not only in terms of the increasingly large number of people seen to be within that demographic, but because contemporary society has often conflated mental illness and learning disability, particularly during what has come to be known as the “great incarceration.”

Simon Jarrett’s book goes some way to addressing this problem and a marvellous — if sometimes disturbing — read it is, too.

Concentrating largely on a British context, Jarrett collects evidence from an eclectic but illuminating array of sources such as court reports, newspaper articles, novels and plays as well as so-called scientific viewpoints that have occupied a more central role.

His main conclusion is that while people with learning disabilities — the “idiots “ of his title — undoubtedly suffered from forms of cruelty and discrimination before the era of institutionalisation, they were nonetheless seen as people who were part and parcel of society, not as something “other” that needed to be kept separate, if not hidden.

As such, they had levels of integration which might well overturn many modern-day assumptions. “Idiots” were partners, family members, work colleagues and citizens who enjoyed active social lives and who worked and owned property. Jarrett argues that if the law did sometimes recognise difference, it did so in a fashion that was surprisingly fair and compassionate.

But from the 18th century, the author argues that narratives started to change fundamentally — and largely for the worse. For the first time, science and the developing medical profession came to view “idiots “ as suffering from an illness, albeit one that they couldn’t really do anything about other than physically isolating those individuals “suffering” from such a condition.

Popular culture, too, began to regard such individuals as unproductive, if not actually dangerous.

Such attitudes became even stronger, with the later influence of the eugenics movement happy to depict learning disabilities as a threat to the vitality of race and nation. It was a vile notion that was often just as much taken up by “progressive” advocates of social engineering as it was by the more expected extreme right.

Jarrett explores the links between how similar rationales were often used to justify the occupation of countries inhabited by “idiot races” — a haunting but often missed connection, and one that leaves a lasting impression as to so how science all too often acts in the interests of political hegemony rather than in the discovery of truth.

Occasionally, when arguments appear to be based on presentations in, say, a particular novel, doubts could be raised as regards the strength of the relevant evidence base, and there is a huge amount of research that cries out to be done in an area that is, admittedly, difficult to substantiate.

And I’m not entirely convinced that the removal of individuals from everyday society took place as a result of power locales forged in the instrumental rationality of the Enlightenment, a position which makes little economic sense in terms of the needs of an emergent capitalist class.

Jarrett assumes consensus on what he means by the terms “idiots, “ and it would have been useful if there had been a greater discussion about this, particularly in the introductory chapters.

There is, for example, a whole school of thought, pioneered by writers such as clinician Richard Bentall, which rejects the notion that psychological distress is always comparable to forms of physical illness and puts forward the case that interventions should be driven far less by diagnostics and more by the problems individuals face.

Although Jarrett’s outlook is unequivocally based on social justice and inclusion, the unrelenting use of the term “idiots” did occasionally make me feel a little uncomfortable. Yet overall this is a fascinating and original contribution, similar in its outlook to Michel Foucault’s highly influential work on the treatment of mental illness within Western society.

The central thesis that those with learning disabilities were often freer, more equal and happier prior to the 18th, 19th and indeed much of the 20th century is provocative, to say the least.

But Jarrett has ably kick-started a long overdue and much needed discussion — let us hope that other voices will follow.