This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

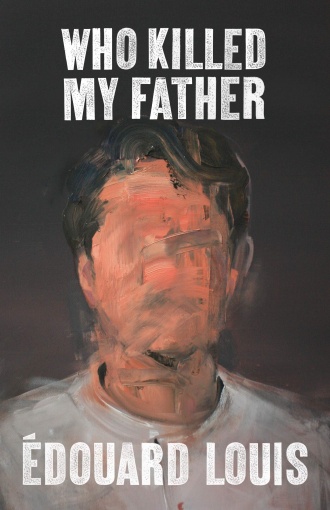

Who Killed My Father

by Edouard Louis

(Harvill Secker, £10.99)

THE LACK of a question mark in Eduard Louis’s spare account of his father’s troubled life and decline is deliberate.

Who Killed My Father is not a traditional murder mystery. It is an indictment of both hyper-masculinity and turbo-charged capitalism, although his father’s life and body is very much a crime scene.

For around half of its 80 pages, the book is almost a lamentation from a gay son about his homophobic father’s inability to accept his sexuality. “Be a man, don’t act like a girl, don’t be a faggot,” seems to be the elder’s personal Holy Trinity.

Through a series of key youthful episodes, Louis recalls occasions when his father’s rejection of his talents, including taking the female lead in a family musical, leads to almost existential doubt and hurt.

Yet the writer also reveals, slowly at first but with gathering momentum, his realisation of his father’s own frustrated attempts at economic and social freedom when a teenager. His escape from a life of factory drudgery is cut short as the centripetal forces of economic servitude draw him back to his home town and then deeper again into marriage and fatherhood.

The father’s rigid and unyielding masculinity is clearly a device to maintain some kind of dignity in an economic and political system designed to rob him blind of everything else.

Louis’s central thesis is summed up in the sentence: “Your life proves that we are not what we do but rather that we are what we haven’t done because the world, or society, stood in our way.”

Indeed, we come to see Louis’s father as far from being a one-dimensional brute and there are shining instances of kindness and empathy towards his son, other children and his stepchildren.

And then the father suffers a terrible back injury at his factory and after months of excruciating pain finds himself paid off and unemployed. What follows is a charge sheet against the French capitalist class of the last 20 years. The indictment sheet contains many familiar names: Chirac, Sarkozy, Hollande and Macron among them.

The assaults of both centre-right and ersatz socialist governments against those on benefits are documented alongside the impact on what remains of the body and dignity of the older man. Forced to take on a menial street-cleaning job, the father is felled under the hammer blows of a liberalised labour system that insists he can work longer for less.

By the end of the book, not only is Louis’s rage at the system fully fledged but his previously Front National-voting father has come round to his world view.

This small but hugely powerful book ends with the two united in compassion, anger and with a mutual resolution that the time has come for a total revolution. The false intersectional divides of age and sexuality are exposed as pretty meaningless in the face of the class struggle.

In this translation by Lorin Stein, Louis has further enhanced his growing reputation as the head of France’s new wave of revolutionary writers.