This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

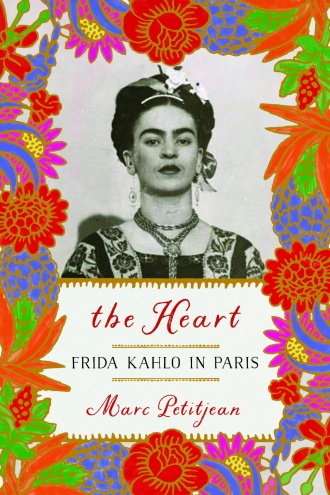

The Heart: Frida Kahlo in Paris

by Marc Petitjean

(Other Press £20.99)

FRIDA KAHLO'S brief stay in the French capital in 1939 was preceded by an equally brief stay in New York City, both encouraged by her husband Diego Rivera.

Mexico’s most famous artist was 20 years older than Frida — and a couple of hundred pounds heavier — and his encouragement was a ruse to get rid of her while he was having an affair with her younger sister.

Such is the attraction or, more likely, the power of men over women, especially during the time when the two were married. In New York City, an exhibition of her work was fairly successful, resulting in the sale of seven of her paintings and commissions for more. Sadly, there were no sales from the exhibition in France but the surrealists did appropriate her work because of its so-called exoticism.

Previously, author of The Surrealist Manifesto Andre Breton and his wife had visited Mexico and stayed with Rivera and Kahlo and promised her that if she came to Paris with her paintings, he would mount a show of her work.

But when Kahlo arrived, he reneged on that plan and suggested a wider “Mexican” exhibition that would include her work. But Breton’s taste was more ethnographic than artistic, so the proposed show included some of the hundreds of Mexican artefacts — “a large number of everyday items” — he had acquired on the Mexican trip. Most were anything but extraordinary.

Worse, when Kahlo arrived, the space that the Bretons had planned for her stay in their apartment was little more than a child’s bed. She fled to a hotel, disturbed by any number of things that Breton has used to take advantage of her.

It was February 1939 and her room was on the sixth floor, without any water, and the bathroom was way down the hall. That was something of a problem because when she was a child Kahlo contracted polio, which left one leg deformed.

Worse, when she was 18, a trolley car ran into the bus she was on and a metal handrail went right through her body. The impalement caused fractures to her body and the abdominal injury acute peritonitis.

Her general health did not recover with the passing years. She underwent many painful operations that necessitated long periods of bed rest and complained of chronic fatigue and pain in her back, legs and feet until the end of her life.

I dwell on these physical complications because they are depicted in one of her most famous paintings, The Heart.

It shows Kahlo with a metal rod through her body, where her heart would be, with a shoe on one foot and what looks like a slipper on the other. To her right, handing on a rope from the sky is a schoolgirl’s uniform, with one arm sticking out of it and, to her left, a Mexican skirt and top, with its single arm looped inside of Kahlo’s left arm.

Her hands are not visible at the ends of the sleeves and — most important — there’s a huge bloody heart on the ground, next to her on her right side.

Kahlo gave The Heart to Michel Petitjean, father of the author of The Heart: Frida Kahlo in Paris, after their two-month affair just before she returned to New York and it’s easy to understand why the surrealists identified with the painting’s grotesqueness. Marc Petitjean says that as a child he observed the painting every day hanging in the family living room.

Michel Petitjean was 29 when he met Kahlo for the first time and she was 32. He described himself as Marcel Duchamp’s assistant and seemed to know all of the surrealists intimately, including Pablo Picasso, Andre Breton, Dora Maar, Salvador Dali and Duchamp.

His son describes his father as a seducer. When he met Kahlo, and after, he was carrying on a lengthy affair with Marie-Laure de Noailles, who had inherited a vast fortune and subsidised many of the artists of the time.

Kahlo had her own share of lovers, including women, before she arrived in Paris, New York and, while still back in Mexico, Leon Trotsky. She claimed to loathe him, except that she admired his politics.

Most of the celebrated artists at the time were leftists or communists and given to free love, including Rivera who, described as physically unattractive, was a great artist.

Petitjean spoke no Spanish and Kahlo no French but their affair was intense, according to the few available documents and witnesses. What it apparently did for her — as well as resulting in her divorce from Rivera after her return to Mexico — was change the perspective of others who began to look at her as Frida Kahlo and no longer as Mrs Rivera. She was freed from her past.

Marc Petitjean ends his account of Frida’s two-month sojourn in Paris by saying that when his father was dying in 1992, he sold The Heart for nearly $1 million. The last sentence in his captivating story of the lovers sadly concludes: “I have never managed to discover who bought it or where in the world it now is.”

At least there is a full-colour reproduction of the painting in the book.

The Heart: Frida Kahlo in Paris is much more than the broken hearts of the two lovers. It’s a song of artistic rebellion, of endless struggle — two components of great art — as well as a kind of swansong of the surrealist movement.

A beautiful book, rendered in a superb translation by Adriana Hunter.

Charles R Larson is Emeritus Professor of Literature at American University, Washington, Twitter: @LarsonChuck. This article first appeared in Counterpunch, counterpunch.org