This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Can you tell us about the book and why you decided to write it as a memoir?

I was very resistant to writing a traditional memoir, and the first draft of the book included very little personal narrative.

I believe the memoir or “creative nonfiction” genre tends to perpetuate neoliberal narratives that eliminate structural critique in favour of emotional identification. Everything becomes about the writer as an individual: their suffering, their triumph, etc. Who cares about the larger set of social relations that make this possible? What matters is what is moving enough to sell copy. So, I knew I didn’t want to play into this.

At the same time, I realised my life was something of a convenient structure onto which I could hang my critique. I was born in 1984, came of age in the post-9/11 landscape, and internalised the liberal obsession with meritocracy. If I was going to make something of myself, I thought, I had to become educated.

The middle-class fantasy of managerial creativity was baked into how I saw the world, and how I imagined solutions to its problems. I had to unlearn all of that. I think the “left” more broadly also needs to unlearn this, and I’m hoping that people will find something useful in reading about my own process.

One of the ways you are clearly hoping that readers will “unlearn” their political outlook is through a more accurate understanding of their class position, and the importance of class-based politics. What is your understanding of class, and your thoughts on how to achieve a cultural shift towards greater class consciousness among working people?

The biggest obstacle for me in understanding class was the cultural and aesthetic markers that are often confused for class: education, taste, lifestyle etc. I grew up in Ohio, surrounded primarily by poor and working-class whites. For a long time, I was ashamed of this fact, and attempted to leave it behind by embracing a stereotypically “cultured” aesthetic.

I placed a lopsided emphasis on individual beliefs and “ideas,” that elusive resource utilised by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and the so-called professional-managerial class. There was something seductive about feeling smart – but at the end of the day it did not change my material conditions. I was still struggling to find reliable work and was in debt from all that schooling I was certain would bring me success.

So I think the first major step in creating class consciousness is to understand that it has nothing to do with individual beliefs and traits of this sort. You probably belong to the same class – the working class – as many of your political adversaries, and while it may feel uncomfortable to demand justice for them as well, it is nevertheless the only progressive way forward.

What I mean is that a majority of workers receive a wage that barely covers their cost of living. It is enough to cover rising costs in housing, food, and insurance, perhaps a credit card or car payment, but not enough to get ahead. Many are not “lucky enough” to even make this much.

These are the conditions that shape the lives of most people. They are material, not cultural, and they unite workers in a way that other categories cannot.

So the left’s best chance at organising a broad movement is to focus on these material conditions that a diverse population has in common. This is of course easier said than done, because cultural divisions are powerful.

Resentment is a logical reaction to suffering, and it is easier to blame someone than it is to accept that your pain is simply the result of an indifferent economic logic. But focusing on material condition is a necessary first step toward creating a political movement that the mass of people will find appealing.

What do you think is the responsibility of cultural workers – artists, poets, writers, film-makers, playmakers etc – to help our class develop and apply a more class-conscious approach to social and political campaigns?

This is a good but difficult question, and one I think about a lot given my own position as a writer who values cultural objects like novels and films. I feel conflicted by the role that works of culture play. I often wonder if art is not inherently conservative, even when its aesthetic is outwardly radical.

There’s one big thing cultural workers can do – and which some already do – and that is to challenge the sort of narratives the market finds so appealing, and that justify the neoliberal worldview of individual adversity and triumph.

Perhaps the role of cultural workers is simply to find ways to make objects that acknowledge this. I think a film like Parasite comes close: it is a film first and foremost about class, and adopts genre tropes to offer a description of class relations which is totally accurate and useful.

Finally, what is your view on the result of the election, in terms of the need to develop and promote class-based, socialist politics in the US?

The 2020 election was in a lot of ways a missed opportunity for class-based politics in America. The “choice” between Biden and Trump was basically aesthetic: which version of austerity do you prefer?

Moving forward, I think there needs to be a serious conversation about what “the left” represents.

A lot of self-described socialists still reflexively approach working people as incapable of contributing to the movement. They are often seen as too reactionary, or too uneducated, unable to participate in the discourse properly.

We need to stop taking our cues from intellectual vanguards and prominent media personalities who remain mired in the culture wars – the material interests of working people are not always represented within this dynamic.

This can make the left’s project alienating and incapable of attracting broad support.

We need to focus more on those material interests that impact a massive segment of the population: wages, health insurance, housing, and debt.

The US economy is not productive in the way it once was, which means the source of exploitation has changed.

Far fewer American workers are being paid to produce goods that other workers buy to realise profits. Focusing our energy on that parasitic model of profit extraction would have the greatest impact in changing the power relations to benefit working people.

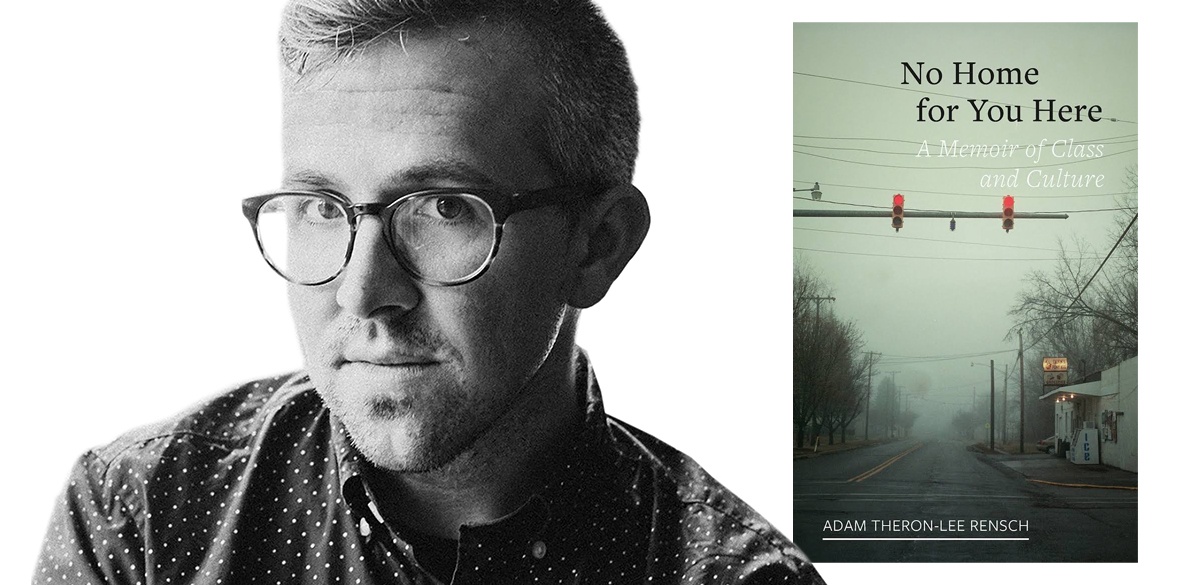

No Home for You Here: A Memoir of Class and Culture, by Adam Theron-Lee Rensch, is published by Reaktion Books. A longer version of this interview is available on the Culture Matters website: culturematters.org.uk/index.php/culture/theory/item/3542-no-home-for-you-here