This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

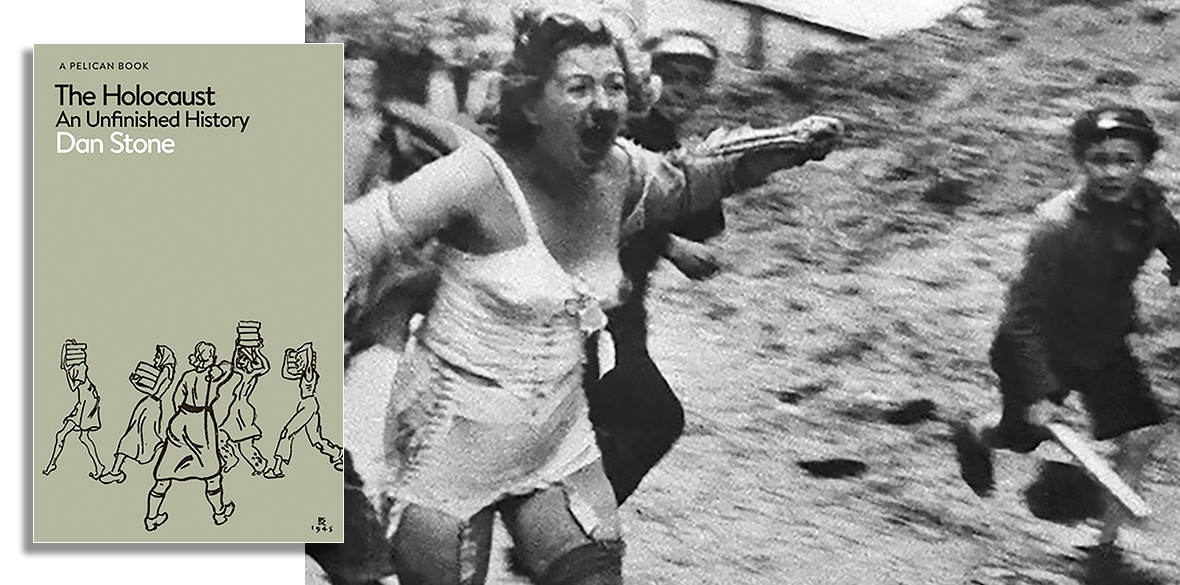

The Holocaust: An Unfinished History

Dan Stone, Pelican , £22.00

THE infamous Arbeit Macht Frei welcome emblazoned over the gates of Auschwitz, along with the deadly mushroom cloud carapace over Hiroshima, is arguably one of two formative images conditioning modern consciousness.

Dan Stone believes we must “move beyond a mechanistic interpretation of industrial genocide” to understand the Holocaust. Rather than a highly efficiently organised and activated transporting, gassing and incinerating of millions of Jews, not to mention Muslim Roma, mentally and physically disabled, homosexuals, trade unionists, communists, Soviet POWs and other “asocials”, almost half of the victims of the Holocaust died of starvation in ghettos or were shot in face-to-face killing actions.

Moreover, while we generally consider the Holocaust to have been first and foremost a German project, without “the almost ubiquitous collaboration across Europe and beyond” the ghastly programme could not have been nearly so extensive.

Under the four main frameworks of trauma, collaboration, genocidal fantasy and post-war consequences, Stone’s book examines the background, the course, and the changing interpretations and influences of the Holocaust since 1945.

He recognises that the Final Solution came about in a series of steps rather than being the result of a single decision, implicit in Hitler’s 1924 Nazi bible, Mein Kampf, culminating in 1942 when Heydrich’s Wannsee Conference stamped SS authority on the program.

Stone’s introduction, What is the Holocaust, presents most of the book’s arguments, including vital observations on the worrying swing to the right in much of our current world.

In his detailed examination of the many roots of Nazism, he cites historical anti-semitism, social Darwinism, popular eugenic theories, the economic impact of the first world war and, interestingly, the ruthless racist behaviour of the great powers in colonialism. However, the basis is essentially racist mysticism, welding together an energetic volkscultuur, a folk unity.

Jews, deprived of citizenship, were until 1941 encouraged to leave Germany and Anschluss Austria, and the Nazis thereby exported increased anti-semitism to reluctant host countries already broadly sympathetic to Hitler’s revitalising regime.

The invasion of Poland saw the take-off of the full extermination programme conducted by the notorious Einsatzgruppen murder squads. Ironically, Hitler’s failure to defeat Britain and its naval sea power in 1940 prevented a Nazi plan to transport huge numbers of European Jews to Madagascar. However, “if what had happened in Poland since September 1939 was shocking, what would take place in the Soviet Union after June 1941 was of another order still.”

While the chapter War of Annihilation’s catalogue of horrors and numbing statistics is not unknown, Stone can surprise, maintaining that these considerable genocidal events “had no impact on the German ability to wage war.”

He underlines the varying responses to Jewish persecution from different areas of what Hanna Arendt called Germany’s “united Europe.” Recent research suggests that “the Holocaust looks like a series of interlocking local genocides carried out under the auspices of a grand project.”

The “free world” does not escape criticism. The Allies’ responses, including the initial coining of the United Nations and the World Refugee Board — offered little more than a “weak mirror image” in matching the scale of the crime.

After covering the roles of more than a thousand subcamps, the death marches and the vast slave labour empire as neglected aspects of the Holocaust history, Stone turns to the aftermath of the mishandled, post-war, long-lasting Displaced Persons camps where, inevitably, Zionism prevailed.

Most important is Stone’s final chapter on Holocaust Memory.

He claims that “selective Holocaust memory is being put at the service of criminalising scholarship” not only in Poland, where recent laws have penalised the defamation of the nation by claiming the country was in any way complicit in the Nazi murder of the Jews.

In 2020 the UK government mandated that universities should adopt the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance working definition of anti-semitism in which seven of the eleven examples of anti-semitism include references to Israel, giving many the impression that the IRHA was more about anti-Israel criticism than protecting Jews.

Readers will recognise the warnings carried by this important book when Stone demonstrates that “The use of Holocaust memory to further nationalistic agendas, to facilitate political alliances on the far right or to ‘expose’ progressive thinkers for their supposed anti-semitism or anti-Israel bias is now a familiar part of the landscape.”