This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE Cato Street Conspiracy — named after the meeting place where the conspirators met near Edgware Road in the West End of London — was an attempt to murder all the British Cabinet ministers and the prime minister Lord Liverpool in 1820.

Most of its members were angered by the economic depression and political repression of the time and planned to assassinate the Cabinet, which on the night of February 23 was supposed to dine together in Lord Liverpool’s Grosvenor Square house.

They would then seize key buildings, overthrow the government and establish a committee of public safety to oversee a radical revolution.

They were prepared to cut the throats of Sidmouth and Castlereagh. The latter, leader of the House of Commons, had crushed the United Irish in 1798.

Lord Sidmouth was the former prime minister who organised a mass hanging to squash Despard’s attempt at a democratic republic in 1803 and who later became home secretary responsible for the Peterloo Massacre.

According to the prosecution at their trial, they had intended to form a provisional government headquartered in the Mansion House.

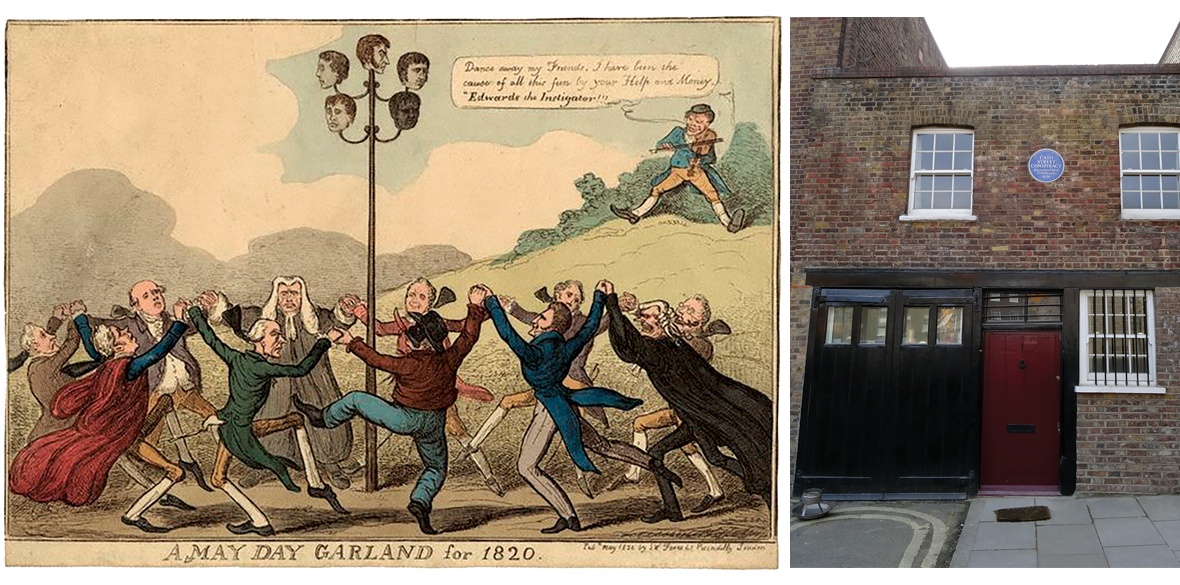

But due to the machinations of agents provocateurs, the conspirators were easily duped and captured above a stables in Cato Street and hanged at Newgate Prison in London on May 1.

The police planted an informer in their ranks, the plotters fell into their trap, and 13 were arrested.

One policeman, Richard Smithers, was killed by conspirator Arthur Thistlewood. Five conspirators were executed and five transported to Australia.

Those hanged and beheaded were a mixed group of radicals. Thistlewood was an apothecary, Tom Brunt an artisan bootmaker, Richard Tidd another shoemaker, James Ing, a butcher and Will Davidson a cabinet maker.

Associated with the Lincolnshire gentry, Thistlewood was of some social status. His great uncle, owner of several plantations in Jamaica, was the worst kind of slaver and at the forefront of imperial acquisition, accumulation and extraction.

His great nephew became a follower of Thomas Spence, the advocate of the people’s farm, perhaps the most direct link between the democratic radicals of the 1790s and the burgeoning forms of socialism, feminism and communism of the 1820s.

Davidson, a man of colour, was descended from Jamaican slaves and a figure in the very long history of African descendants in England.

Yet modern capitalist slavery is the pertinent background to Davidson — he repeatedly cites, and even recites, Magna Carta.

He was responsible for drafting a constitution, while others dealt with the equal division of lands, or annual elections, or redistribution of wealth.

When asked what she would be responsible for, Tidd’s daughter replies in a flash: “The committee for the care of unwanted children and orphans. There will be no need for “scrumping” — appropriating apples from private apple trees.”

How widespread the Cato Street conspiracy was is uncertain. It was a time of unrest and rumours abounded.

Malcolm Chase noted that “the London-Irish community and a number of trade societies, notably shoemakers, were prepared to lend support, while unrest and awareness of a planned rising were widespread in the industrial north and on Clydeside.”

The conspirators were Spencean Philanthropists and took their name from the British radical speaker Thomas Spence.

It was known for being a revolutionary organisation, involved in unrest and propaganda and plotting the overthrow of the government.

That May Day hanging of the conspirators is not at the centre of the wonderful historical novel Turtle Soup for the King by Judy Meewezen.

It’s scarcely alluded to, though if you want a study of the hangings read Vic Gatrell — how they took a pinch of snuff or sucked on oranges, how they advised the placement of the noose, how they denied religion and how the crowd yelled “butter fingers” when the executioner dropped a decapitated head.

The king in question in the book’s title was George IV, “the most disreputable and unrespected monarch who has ever sat upon the British throne,” wrote the historians of the common people. His father George III, a tyrant gone insane, had died in January 1820.

As for the turtle soup, it was the soup of the age for royalty, aristocrats and the big bourgeoisie.

Starting in the 1740s, their palates were tickled by the majestic creatures and they continued to slurp into the 1860s.

Imported from the slave islands of the Caribbean, lords, ladies, and fat cats consumed these ancient animals to virtual extinction.

Turtle soup was fattening but not as fattening as the proletariat, whose labours royalty and their ilk gorged upon.

The ruling class consumed the proletariat not so much at table as at loom, plough and wheel or by massacre and the noose.

Meewezen’s historical novel is based largely on the documentation of spies, police, informers, turncoats and provocateurs on the one hand and, on the other, the documentation of the trade union movement, reform politicians, the radical press and an archive that was already censored or in peril of extinction.

The conspiracy arose after the Manchester massacre in St Peter’s Field — “Peterloo” —in August 1819, when men, women and children were slashed dead with sabres wielded by charging Hussars of the crown. The proletariat was enraged, hurt, traumatised and hungering for revenge.

Its revolutionary traditions included insurrection, the art of taking over a government by force. Yet, tender in its grief, the proletariat was vulnerable to ruling-class provocation nipping it in the bud.

The Cato Street Conspiracy was a kind of epilogue to the insurrectionary impulses that had punctuated English class relations from the Despard conspiracy of 1803, through the Luddite attacks on machinery (1811), the dislocations and dearths (“bread or blood”) following the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars (Waterloo, 1815), concluding with Peterloo.

Irish disturbances, Scottish uprisings, Caribbean slave rebellions and colonial resistance from India to Cape Town — thousands of Xhosa attacked Grahamstown in 1819 — accompanied, influenced, or reflected these conflicts in England.

The May Day hangings in 1820 were at a conjuncture embracing the organisation of the cotton spinners and weavers in Scotland, the migration of the Irish to England, one of whom, Bronterre O’Brien, coined the expression “moral economy,” signifying not communism certainly but not neoliberalism either.

Events in the novel are viewed through a microscope, from the perspective of the wives, women and their children.

Misadventures and calamities affecting children and poor women occur well apart from the pompous, and manly, events of official narratives. Under the subtle pen of Meewezen, the dramas of kitchen and alley are as gripping as those of the patriarchs’ public forums.

These proletarians are close to starving and, as in The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens, rarely does a page go by without reference to something to eat.

Molly, Thomas Brunt’s wife, cuts up a flannel sheet into little squares later to be made into gunpowder cartridges.

It’s a monotonous task, so she relieves her mind by construing the men’s whispers as so much babble which would one day lead to paradise. For her, that meant a full pantry. Susan Thistlewood stands out in these pages for her courage and intelligence and, at the end, two of the widows and the children share house.

The women have the “determination that the children of heroes should face the world with pride, engaging their hearts their brains and all their talents in the construction of a better world for all.”

Turtle Soup for the King would make an ideal TV series. There are five threads for each of those hanged and decapitated — Thistlewood, Brunt, Ing, Davidson and Tidd — and the Judas of the plot is the villainous engineer and police informer Thomas Edwards, Thistlewood’s second-in-command.

The whole is divided into two parts, each structured in chapters broken into sections full of similes and fascinating asides such as on the clogs worn by the northern spinners and weavers at Peterloo.

The new king’s coronation feast starts with three soups and hundreds of side dishes, sauces and desserts.

“If it’s not over-salted,” says his majesty, “let us start with the turtle.” Writing on death row, Ings asked that his body be conveyed to the king “that his majesty, or his cooks, might make turtle soup of it.”

After such a generous gesture of sacrifice, justice can only reply: “Eat the rich.”

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in Counterpunch (counterpunch.org).