This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Nobody Loves You and You Don’t Deserve To Exist

by Brett Gregory

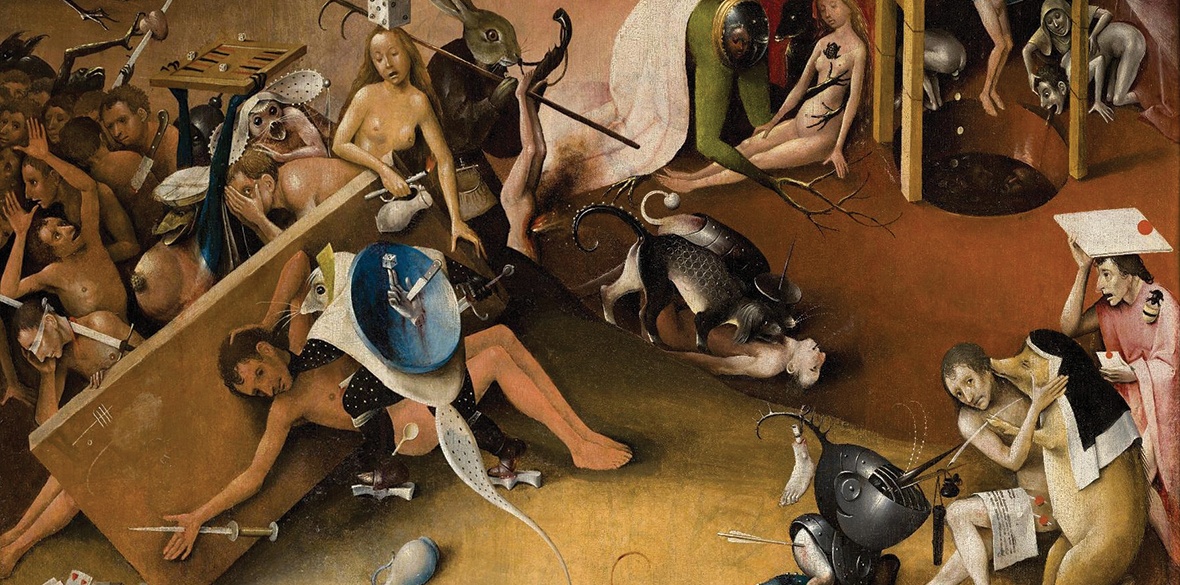

IN HIS painting called The Garden of Earthly Delights, Hieronymous Bosch presents a radical, disturbingly surreal critique of the suffering in the class-ridden society of the Middle Ages, from the point of view of the lower layers of that society.

His images represent the cruelty and the suffering endured by the poor, the physical and psychological damage of poverty, poor mental, physical and spiritual health, and the chaotic, fearful, precarious horror of their lives.

The painting itself appears in many of the scenes of Nobody Loves You and Brett Gregory’s film is its modern equivalent. It’s an equally searing critical vision of modern Britain, from the perspective of a northern working class who over the last 50 years have been struggling with the interlinked problems of deindustrialisation, drug and alcohol abuse, depression and despair, all generated or magnified by neoliberal late capitalism.

The film recounts the life of Jack, grieving the death and disappearance of close friends and looking back at his life from the midst of the recent coronavirus pandemic.

Through a haze of drink and drugs he reviews both sad and comic episodes in a childhood marked by abuse and cruelty, and an adolescence and adulthood marked by the social breakdown of working-class communities under the impact of the the Tories’ assault on industry and undermining of the welfare state.

The story is told through flashbacks with voiceover and a series of striking tableaux of talking heads, with an accompanying mediaeval-sounding soundtrack, and occasional discordant interventions from a posh-voiced grandmother trying unsuccessfully to communicate with and admonish Jack.

Looking at the tortured, suffering figures in Bosch’s painting is not a pleasing, feel-good experience and this film is not an easy watch. It’s complex and multilayered, referencing not only Bosch’s painting but Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and numerous other literary and cinematic works.

Like the painting and other modern surrealist artworks, it’s a deliberately jarring, unpredictable and discomforting film, keeping the viewer on edge.

The bedtime-story tones of the voiceover grate with Jack’s toxic masculine anger, and the tableaux of successive women who tell the story of his life are like troubling dreams, still lives from the brush of a surrealist painter.

Above all Brett Gregory’s serio-comic writing, mostly spoken by very good actors in long monologues, is surreal, self-aware and full of ironic asides and references. It produces a Brechtian effect of alienation, preventing the viewer from emotional involvement with the characters and fostering an awareness of the theatricality of the film which contrasts with the cruel reality of the struggles and suffering it depicts.

Both the content of the film and the way it’s made jolt the viewer aesthetically, conveying a sense of the broken psychological and physical health of individuals and the breakdown of social relationships in families and shattered communities.

The content, strong imagery and forceful editing has a shocking brutality which is a kind of mimetic counterpoint to the brutality of life for the poor and precarious.

It is also perhaps a hint of what’s needed to break with and revolutionise the status quo, to liberate people like Jack from an oppressive state, an exploitative economy and a compromised, compliant and collaborative culture.

Despite being filmed on a micro-budget, leaving its maker in debt and facing the meanness of the British Universal Credit benefits system, the film has won over 50 international awards since its release earlier this year.

Its unsparing and original portrayal of modern British life from a working-class perspective is not the straightforward social realism of Ken Loach or Mike Leigh. It’s a complex and original kind of social surrealism, although the film deals with similar issues and focuses on the same precarious layer of proletarian life that Loach does, and which Marx and Engels documented in 19th-century Manchester. The same class which — just as they predicted — has been economically and psychologically immiserated over the last 50 years by capitalism and class division.

Nobody Loves You and You Don’t Deserve to Exist is available to watch on Amazon Prime. If you would like to screen the film in your local community, contact Brett Gregory at Serious Feather for a free copy. Mike Quille is editor at Culture Matters, www.culturematters.org.uk.