This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

That’s Not My Name

Golden Goose Theatre

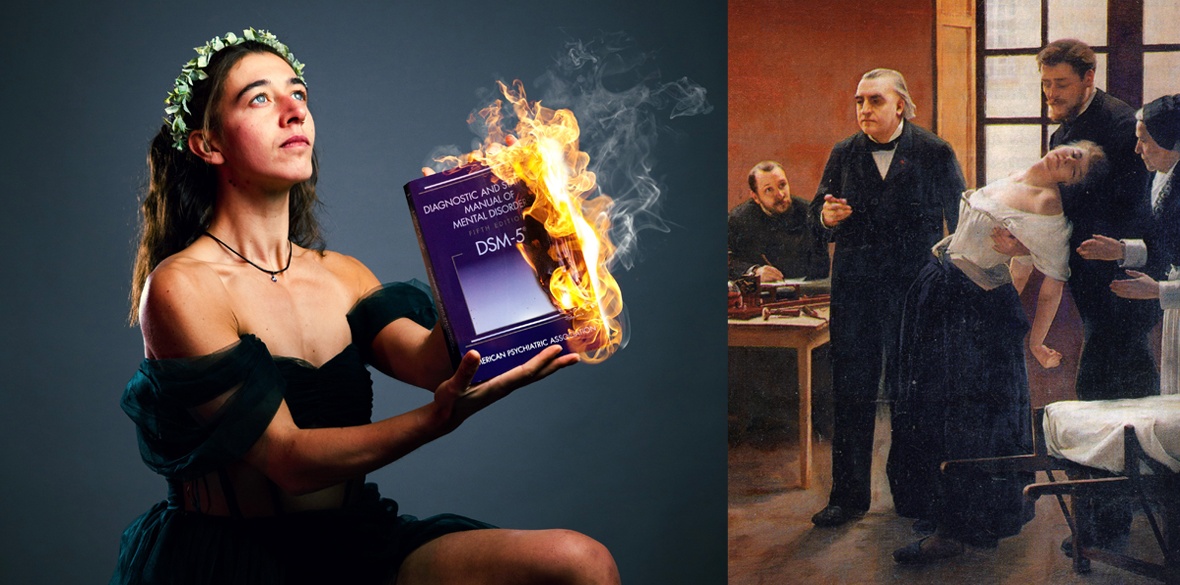

IN a tent by a tempestuous sea, a young woman is having a tantrum on the floor. Crisps are everywhere, bar where are they supposed to be. Is this normal? Well, that’s kind of the point of That’s Not My Name, an eloquent, scattershot broadside at modern psychiatry.

Sammy Trotman is white, privileged, and heavily pathologised. Borderline personality disorder. Dissociative personality disorder. A narcissist, perhaps. A sociopath? As this show explains, in its own, often unfocused way, a lot of these labels rely on context. And what matters, perhaps, is the cycle of trauma, and how we break it.

In short, this is not a great advert for late capitalism, even if you have the wealth to circumnavigate our collapsing mental health services.

Though not overt, the personal is always political, and Trotman makes funny, subtle observations about the role of wealthy, powerful men in society — in this case, senior doctors and smug psychiatrists.

These reminded me of Noam Chomsky baffling Andrew Marr with the possibility he had landed as BBC political editor not because of his searing journalism; but because he is of exactly the right background and personality not to challenge the status quo.

A mixture of stand-up, performance poetry and monologue, Trotman is a compelling performer, whether she’s doing the splits, bullying an underling, or emerging from the wings dressed in a Waitrose bag for life.

We hear of a relationship with an older man in brutal detail. The horrors and the abuses of boarding school. Vodka in a toddler cup, skits performed in a mental hospital, and friends who don’t understand they’ve been successfully manipulated. And the question: Do athletes have an exercise disorder?

The conceit that this show is unscripted, like some of the interaction with techy and the hapless assistant, feels unnecessary. I did, however, enjoy the microphone being positioned to the side of the stage, used seemingly at random. As with the crisps — whether symbolic, metaphorical, or unplanned, it helped ram home the idea that life’s messiness doesn’t end when you perform it in front of other people, like a lot of us are doing every day.

The crowd work, too, is artfully awkward. If you struggle with empathy, why should you listen to an audience member tell you about their life, even if you’re the one who asked in the first place? Again, the poor underling — actually, I suspect, the director of the show — is on hand, here, redistributing treats that have been offered and then immediately withdrawn by our lead.

The stage is a good place for a narcissist. As Trotman observes, some people crave money, and some crave attention, and it’s not difficult to see which category she belongs to.

But the rawness, the lack of obvious structure, and refusal to package this into something more consumable makes it feel like something new, with its message and its performer lingering in the mind long after the lights go out.

Golden Goose theatre, London, May 19-20; Brighton Fringe, June 2-3 Info: goldengoosetheatre.co.uk; brightonfringe.org