This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Capital is Dead: Is This Something Worse?

by McKenzie Wark

Verso, £14.99

Rereading Marx in the Age of Digital Capitalism

by Christian Fuchs

Pluto Press, £19.99

DIGITAL technology has been dislodged from the political agenda by Brexit, political corruption and fears for the NHS. It occasionally flickers at the borders of our awareness but we’re failing to assess its impact and implications.

In the past couple of years there have been well-informed attempts to raise the focus in books dealing with robot teachers, online filter bubbles, AI and employment, profiling, surveillance and the digital quantification of human affairs.

Yet what is now needed are analyses that draw on this developing literature to provide a coherent account of the transformations of class and power wrought by the digital age.

The latest books by McKenzie Wark and Christian Fuchs offer frameworks for thinking about the digital world and consider the extent to which its tools create social and economic crises. And they assess the possibility that technology can be reclaimed from serving the interests of powerful institutions.

Fuchs and Wark agree in their diagnoses of the difficulties faced but the ways in which they respond have little in common.

Wark is an iconoclast. As the title of her book implies, she believes capital is dead and power is determined by the ownership of information. IT has made its core product abundant and cheap, while concentrating it in the hands of the already wealthy. As a result, we are becoming more disempowered than ever.

The book takes the form of an extended thought experiment, the conclusion of which is that our political language has not stood the test of time. Marxism is deemed unable to account for a series of developments since the 1970s: the wholesale commodification of every aspect of existence, the multi-layered nature of information-based production and the fact that we deal with information vectors — positions and movements — rather than products.

It is argued that a new “vectoralist” class has displaced the old industrialists in the same way that factory owners displaced feudal landlords. This has been achieved through the exploitation of the hacker class – those engaged in the production or communication of digital information.

The abstract nature of information creates a separation between human production and the environment in which it takes place and Wark is persuasive in arguing that this tendency is a key factor in humanity’s trajectory towards ecological disaster.

Revolution, she suggests, might come from technical specialists pooling and reconfiguring knowledge to shape the forces of production into beneficial and human-centred forms.

In calling for new, “vulgar” forms of Marxism as opposed to the “genteel” or “literary” variety, Wark creates a paradox. Her argument is informed by a “vulgar” practical experience of digital tools but is presented within a “literary” work, rooted in an established academic tradition.

Perhaps she is implying that traditional academic research is no substitute for technical knowledge and situated experience when it comes to wresting power from the new ruling class but I’m far from sure — it’s a pity that many of Wark’s ideas are expressed in convoluted and impenetrable prose.

And I don’t feel that she has provided compelling evidence that the advent of digital technology has rendered Marx’s thinking any less relevant.

Christian Fuchs’s Rereading Marx in the Age of Digital Capitalism is clear and specific. He rejects Francis Fukuyama’s notion of the end of history advanced in 1992 and notes the resurgence of Marxian-inspired theory and practice over the last decade.

He demonstrates that Marx remains relevant to the age of social media, sometimes in surprising ways. For example, the traditional idea of commodity fetishism is that it masks social relations but the social character of Facebook itself veils our interaction with commodities.

Fuchs highlights the value of Marx’s dialectics in understanding the fundamental contradictions of digital media under capitalism. There are users who want to download artistic content without paying and there are media corporations using intellectual property rights and surveillance to limit file sharing.

Then there is the additional contradiction between those who make a living by limiting access to content and those who use content as a giveaway to promote their targeted advertising.

Fuchs points out that Facebook, Twitter and Google exist only as the outcome of social relationships between human beings but are, like all privately owned corporations, incompletely social. Marx’s critical theory, he argues, suggests that true social media can only exist in a commons-based participatory democracy.

Fuchs considers Marx’s critical sociology of technology, originally set out in fragments across a range of works. This encompasses dehumanisation, alienation, surplus value and social problems.

Positions such as techno-determinism, social constructionism, technological optimism and technological pessimism, Fuchs contends, focus on individual factors while Marxian analysis shows the uses and abuses of digital technology to be determined by the outcome of social struggles.

Marx’s approach can also provide the building blocks for a critical theory of communication. Fuchs explains that Marx defined the struggle for socialist alternatives in terms of people rediscovering their identity as social beings. True communication can only take place in a “community of commons,” where communication tools and techniques are independent of commerce.

A Marxist model of communication technology can, Fuchs suggests, encompass issues such as ideology, fetishism, knowledge and globalisation.

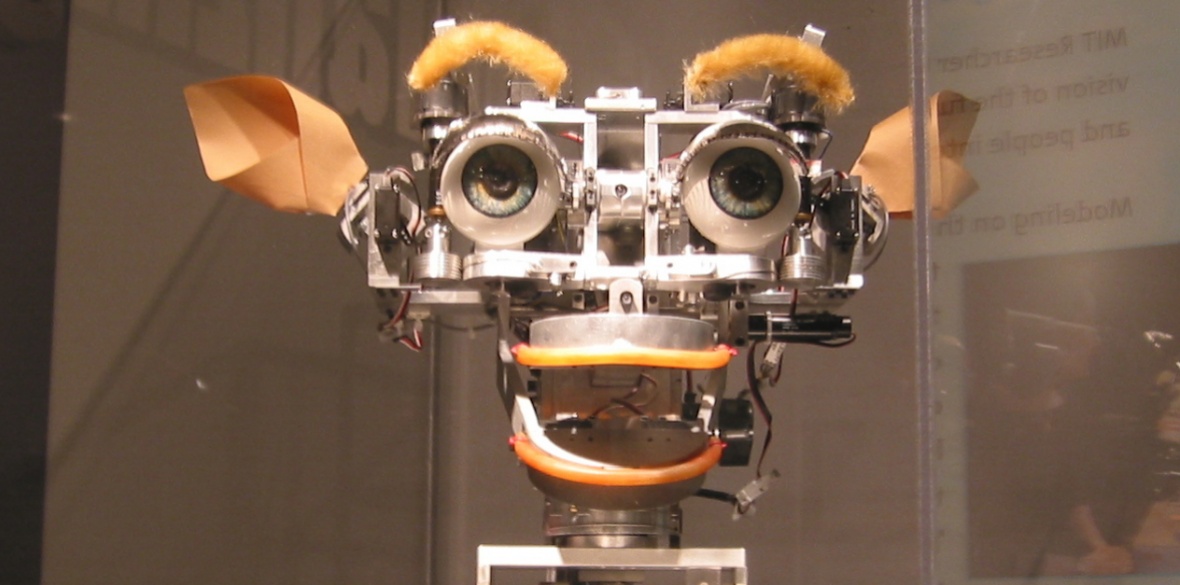

Further evidence of the urgent need to re-engage with Marxian analysis is provided via a case study of Industry 4.0. This refers to the technologies controlling the Internet of Things — the everyday objects such as big data, AI, robotics and automated production and distribution. Fuchs shows that the ideology underpinning these technologies requires a massive reduction in labour costs.

Digital tools and networks are redefining our world, so we need theoretical frameworks that support the development of human-centred technologies.

McKenzie Wark’s call for an experimental, vulgar form of revolutionary approach to digital commodification is a challenging read, full of provocative observation but I found more hope, and practical value, in Christian Fuchs’s lucid demonstration that Marx’s writing contains an adaptable and resilient foundation for digital socialism.