This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

ANY novel about the Troubles makes a statement, feeding into the way history will record those times and how new generations will see them.

Not only is there an “official” version, there are also the real experiences of both communities in Northern Ireland and their varying interpretations of them.

Anna Burns’s Milkman, which won the Man Booker Prize last October, reads like a dystopian novel. It’s set in a time and place where names are not mentioned, places not named and where people are referred to in terms of their relationship to the anonymous narrator or by another designation.

Almost everything is expressed indirectly, by innuendo. The narrative style of the novel reflects the coded talk of Belfast, where names reveal an either/or identity and pronunciation is a shibboleth.

The world presented is at the same time both dystopian and recognisably Belfast — specifically Catholic working-class Ardoyne in the 1970s — during times as horrendous as Burns describes.

She conveys this by highlighting the madness in a surreal narrative, with frequent tangents, before returning to the main storyline. This can make for challenging reading.

Ardoyne is a Catholic enclave in Protestant North Belfast, one of a number of Catholic areas in the city that are completely isolated and therefore more vulnerable.

The neighbourhood is written into the novel in many ways — in the unnamed geographical detail and, above all, in the way people speak. The title itself expresses the book’s Belfast and North of Ireland theme — Milkman refers to the clandestine transport of explosives in milk crates into the Catholic areas.

The word “Catholic” is never used and neither is “Protestant.” Instead, there are “renouncers-of-the-state” and “defenders-of-the-state,” those who look “across the border,” the others “across the water.”

The suggestion is that the micro-culture of everyday life is the same in both communities yet the narrator expresses the experience of the nationalist working-class community.

Reflecting incorrect general usage, the narrator refers to the two Christian denominations as “opposite” religions. The twain only meet in the city centre in mixed bars and, unexpectedly, in a French evening class.

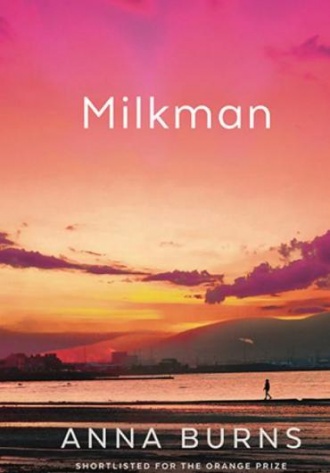

Here, the teacher struggles to get students to see the apparently familiar differently. Indeed, the students are sent out to look at a sunset over Belfast Lough — the only vivid colour in the novel and the colour that defines the book’s striking cover.

The milkman of the title is a 41-year-old paramilitary sexual predator stalking the narrator. She is the 18-year-old daughter of a widowed working-class mother in this particular community, one under siege by the British state and its “defenders.” But, explicitly, the narrator is on the margins of this community.

Her perspective does not relate to the experience of the core of the community, which is probably why the novel has not been happily received by all.

Her viewpoint is that the “renouncers” control her, as they do the entire community. She is not involved in their activities, yet there is little she can do to separate herself and live an independent life.

Milkman and another paramilitary pursue and attempt to coerce her. At the same time, the narrator does not hide the fact that this crazy situation results from the aggressive, humiliating and controlling treatment of the community by the armed forces of the occupying state.

The absence of colour, of smells and taste, is acute. People in this place and at this time do not experience life fully. This is a half-life in the shadows, deprived and diminished by severe restrictions, curfews, unnerving total observation by state and “renouncers,” brutality and violent deaths. Those killings and deaths, due to the all-pervasive violence, far outweigh natural deaths.

Every family here has lost at least one relative, frequently more. Those who remember those days know how true this feels. Even children cannot imagine non-violent deaths but the novel does not detail these graphically. The violence is not explicit, just its effect on the people within the community, its toll on their personal freedom and entitlement to human living.

Part of this dystopian feeling of greyness and absence of humaneness comes from the novel’s statement that people feel unentitled to happiness, especially to a fulfilling and loving relationship with a partner. Relationships are broken off when partners get too close and this adds significantly to the feeling of an incomplete life lived on the margins.

Only the burst of colour when the students of the French class are sent out to witness the sunset over Belfast Lough indicates that another way of life is possible, one which is cross-community.

The narrator reads books while walking but they’re ones predating the 20th century — she wants nothing to do with the reality around her and actively tries to separate herself from it, though she is not entirely successful.

Despite the sense of entrapment, some of the community in the novel rebel and look for happiness. Others who stand out for their resistance are women such as the traditional housewives who break the curfew and engage in bin-lid banging to alert neighbours to danger. Early feminists also make an appearance.

In documenting aspects of the working-class experience of the Troubles, Milkman is a reminder of the bad old days. It is an experience defined above all by the military force of the imperialist British state and the responses such violence and oppression creates in a besieged and divided population.